Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I like strange games. I’m not ashamed to say so. I’m not always good at the games I love, and I would not likely nominate them for any sort of award. I see something in them that closely aligns with something in me and I vigilantly hold them tight. Not physically—that would be weird; but definitely in a slightly awkward emotional way.

Here’s the trouble with loving strange games. They are the hardest ones to get to the table. Sometimes the theme is less accessible or the mechanics a bit out of kilter. Maybe the artistic choices are eclectic and distracting. More than likely they are games whose souls require the sort of connection that is willing to overlook minor faults to find joy in the guts of the thing. The truth is, they are not for everyone. The question, then, is whether there is another person or people in my life for whom the game is also right—or whether I must more seriously consider solo gaming.

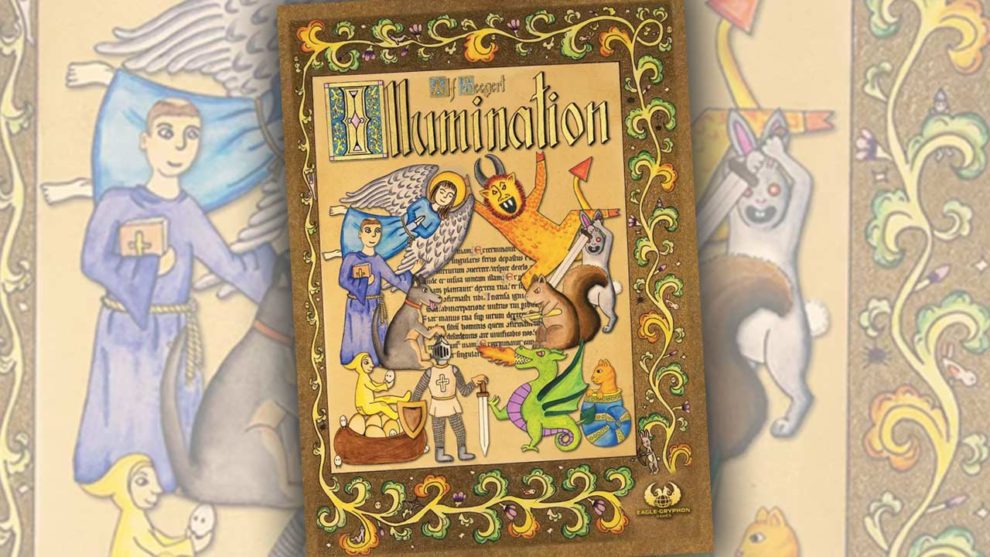

Illumination from Eagle-Gryphon Games is the second Alf Seegert title I’ve set out to review. The first, The Road to Canterbury, was for two or three players (read: awkward) who become Chaucer’s (read: inaccessible) corrupt Pardoners, tempting pilgrims toward their death (read; morbid) while simultaneously offering pardons for cash (read: twisted). I loved it then and still do, though it is not frequent enough a visitor to our table for all the reasons cited. Still I was more than enthusiastic to tap into another of his titles, even though I had a feeling I might face the same situation.

I was right about the struggle. But I was also right in believing Illumination would resonate with my gaming heart.

Illumination is a two player area control skirmish game with a hint of set collection and a bucketful of unrestrained possibility as reverent and irreverent monks attempt to add their brand of quirky illustrations to an illuminated manuscript of old.

Simple, and not so simple

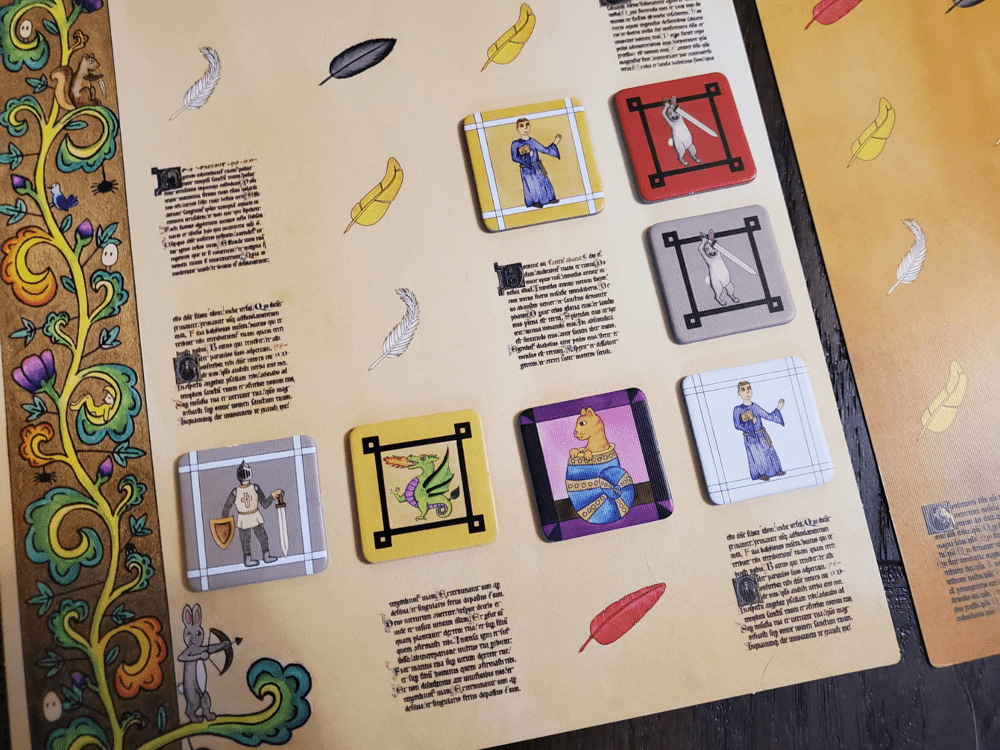

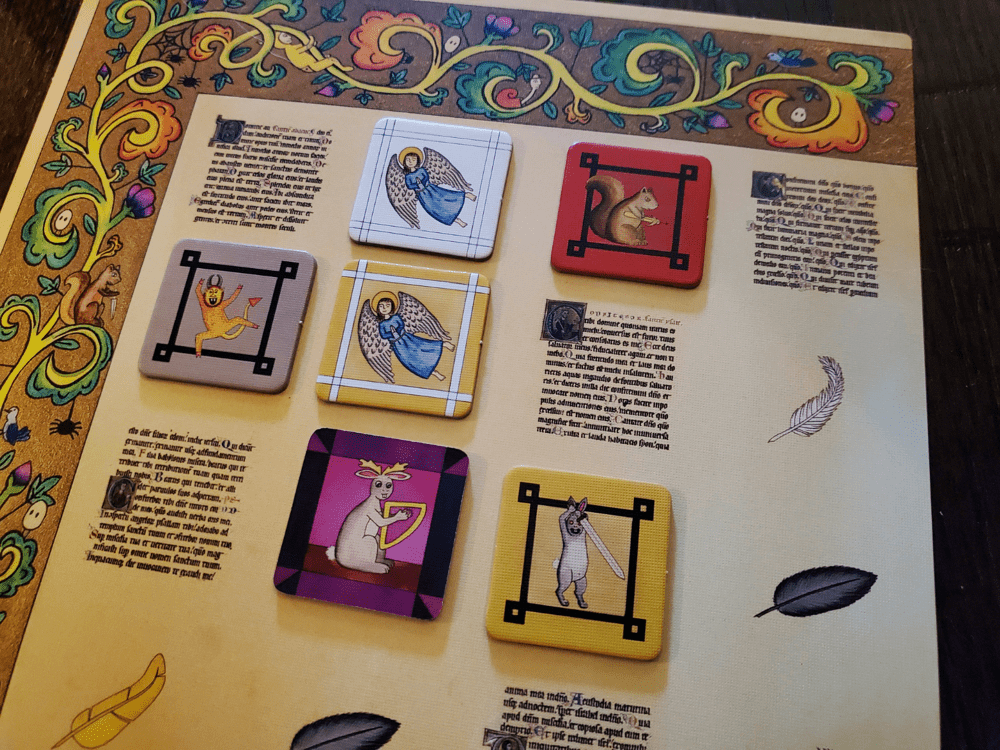

Illumination takes place on three manuscript pages, each effectively a 4×6 grid with some of the squares blocked off by text or decorative flourishes. Each monk controls a group of illustrated images that are perennially at war: knights and dragons, angels and demons, monks and evil bunnies, and dogs and armed squirrels. These images will find their way to the pages via tiles, earning placement bonuses and vying for “geographic” control by outnumbering their counterparts.

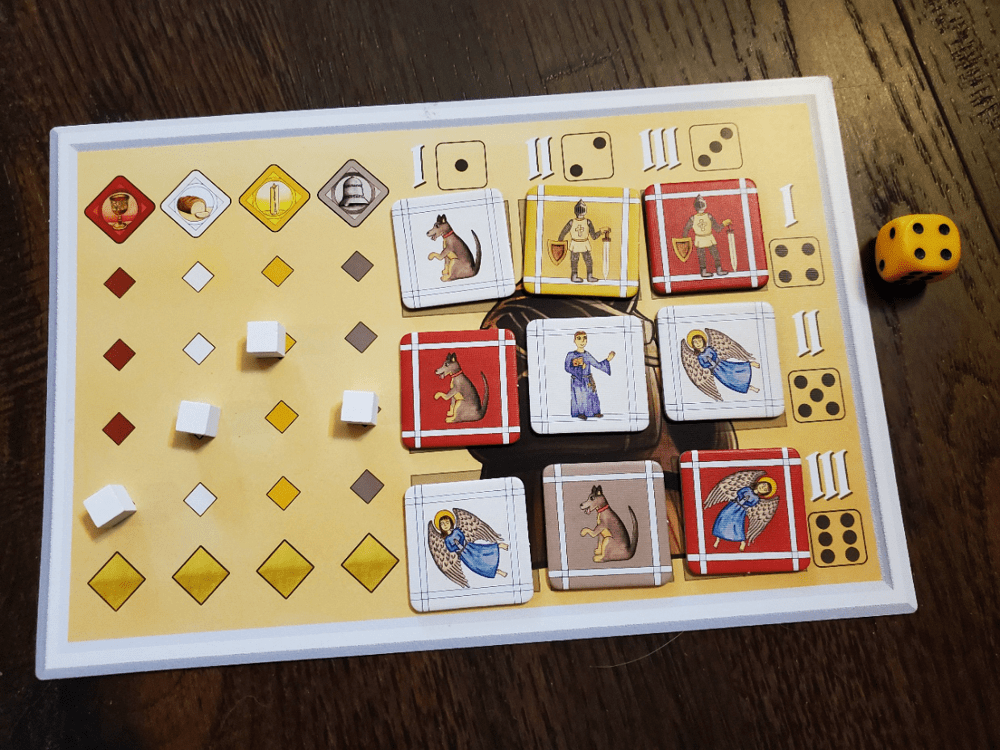

On each turn, players work from their 3×3 grid of tiles in which the rows and columns each correspond to one of the three pages. Selecting one row or column, players must add the tiles to the pages, taking several things into consideration. Each available space is marked by a quill of red, white, yellow, or black/gray. If the tile color matches the quill color, the player receives one coin. If a tile is placed next to another tile of the matching color, the player receives one of the game’s four Ritual tokens—again red (wine), white (bread) yellow (candle), or black/gray (bell)—for each match.

The aim in tile placement is to engage counterpart tiles in battle. Place angels next to demons so as to outnumber them in adjacent groupings around the page—that sort of thing. An engaged battle continues until it becomes bounded—the game’s most unique concept. Bounded means no more tokens can be added to that skirmish. In other words, when adjacent dogs and squirrels are suddenly surrounded by other tokens, text, and the page’s edge such that the battle simply has no more room to grow, the player with the most tiles involved wins. The losing tiles are flipped face-down, the losing player receiving a coin for each, while the winning player places a cube on the battle card of the participating images and the game goes on. The battle cards keep track of each of the four skirmishes as the game progresses. The winner of each card receives 5 points at the end of the game.

Of course, the other aim in tile placement is collecting coins and Ritual tokens. Sets of 3/4/5 matching Ritual tokens can be cashed in on the monastery board for 2/4/7 points, respectively. This set collection is a side hustle that serves to provide somewhere between one third and one half of a player’s total points. Each bonus on the monastery board only issues once, so it is imperative to work efficiently to claim the best scores. For every cube placed there, the opponent receives a Scriptorium card. Ritual tokens can also be used as coins (though not vice versa).

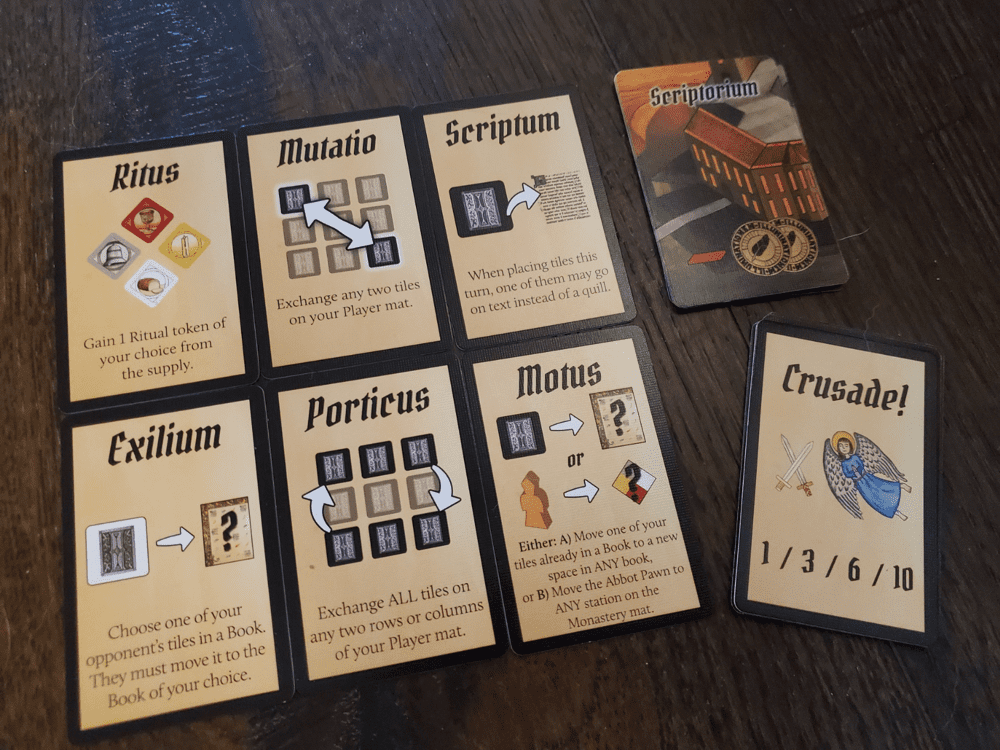

Coins serve multiple purposes. First is buying Scriptorium cards. Each player has a deck of these ability cards that can be spent without restriction once purchased. These cards might allow for swapping tiles or entire rows of tiles on the player board to engage a different page. The second use is moving tiles from their intended page to another before placement, one coin per move. Finally, coins are used with the monastery board to move the abbot to the matching Ritual token space before cashing in a set.

Illumination continues until the three pages are full. The player who fills the final space on each page receives a Ritual token as a bonus. Any tiles that cannot be placed move to the sheep’s pen for a loss of endgame points, which is why Passing is always an option when the game’s end nears. Final scores consist of face-up tiles, battle card results, monastery board results, and a Crusade card which grants points based on the number of a specific tile defeated in the game.

Stumbling blocks

As a production, Illumination is not impressive. The manuscript pages are closer to pages than they are boards. The monastery board is also heavy cardstock. The tiles are standard, as are the coins and cards. The cubes are cubes and the abbot meeple is as ordinary as ordinary can be. The artwork is as quirky and unusual as that found in old manuscripts with images that make you scratch your head and wonder what, exactly, was in the incense.

And yet, much like the more recent edition of The Road to Canterbury, I don’t mind the minimalist approach a bit—primarily because the play’s the thing. There is nothing in this title that begs for superfluous deluxification; no component that makes me wish it were made of metal or chunky wood. I say bring on the awkward glory of it all. The box is low profile, sturdy, and manageable. The artwork is authentic and endearing. The pages are pages. And the battles are fascinating.

The rulebook is good, but at times it feels like an unpaved onramp. Undoubtedly the most challenging concept is the bounded battle. It is laid out fairly well on a page after the “End of Game” section in the book. Personally, this was my greatest stumbling block because this concept is the game and I read through the whole game the first time without a farthing of purpose. The gameplay portion should probably say: READ PAGE 7 FIRST.

In teaching the game, I’ve also found the bounded battle to be the speed bump. Folks understand collecting and cashing in coins and tokens. In a generic sense, everyone understands area battles—have more a than b, more x than y. But bounded?

I think orthogonal adjacency causes most of the confusion. A battle must be surrounded in order to resolve, but the lack of regard for the diagonal prompts the occasional double-take to determine when you’ve actually won. Until your eyes adjust to seeing the boundaries as they are intended, you may miss opportunities to close a battle or fail to defend yourself in the face of imminent demise.

A friend likened bounded battles to the pencil game on a kid’s diner menu in which you are adding segments of a grid of squares, and whoever closes a box gets to put their initial inside. You spend the game in the tension of only wanting to close the box when it’s to your benefit. Illumination can feel like that, but only orthogonally connected tiles contribute to the tension, and coins, cards, and Ritual tokens loom to tip the scales just long enough to create opportunity.

As I’ve discovered: it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. But it is mine.

The mystic monk

Illumination is one of the few games for which I was drawn to the solo mode because of a love of the game and a lack of partners. I typically only engage solo play for reviews, but here I wanted to know more, just in case I never find another partner.

The solo opponent is the mystic monk. He is a battle-focused machine who passively collects Ritual tokens on the side. He begins the game with an advantage on every battle card, with the number of cubes determining the difficulty of the game. The primary objective is neutralizing his advantages amid the hope of claiming one outright.

I think the solo mode is fantastic both for play and for exploring Illumination’s soul. The mystic monk’s placement preferences are easy enough to follow: from top to bottom, left to right starting on the intended page and progressing through the pages, place the tile near: 1) the first opposing tile, 2) the first like tile. If all three pages fail then: 3) the first matching quill, or 4) discard. He is not bothered by coins and cards, and his token collection is automatic based on the color tile he places. His tiles and starting page are determined by the roll of a die. He is a breeze to maintain.

He even has a special ability all his own in that when a “collect two coins” tile pops up as they are wont to do, it bolsters his next placement to be worth double in the fight. This adds a fun wrinkle and unexpected urgency to certain battles.

Seegert’s choices with the monk further reveal the heart and hierarchy of significance within Illumination. Battle first, battle ever. Enjoy the spoils, but only as the spoils of battle.

A bit of celebration

I love that the conflict is not between good and evil, but between reverence and irreverence. One monk with an ornery creative side trying to slip red-eyed sword-swinging bunnies into the text of the Gospel of John or some other significant text makes me smile. Illumination has a lighter heart than a typical skirmish game. Regardless of the outcome, thematically, the world is blessed with a consequential truth in print. The finished pages are charming in that way.

Hesitations and early confusions aside, if you come to see the boundaries as you ought, there is a delightful struggle to engage. The manuscript pages are two-sided with different layouts to present unique situations and unique interruptions to every perfect plan. The page is as much involved in the wrestling as the players.

There is a nice concentric flow to the game. Each page begins with a single Drollery tile—a neutral illumination with a purple background—that serves as an epicenter and a reward point, granting a Ritual token to any adjacent tile. These anchors suggest points of early engagement without being heavy handed. Go as you will, but the Drollery cries out.

The white and black boards are asymmetric. The white player begins with only one coin but a blank slate to establish advantages. The black player, much like in chess, begins with an eye towards reaction, having five coins to scatter tiles early in response. Within a turn or two the players are even in their tokens, cards, coins, and board presence—and the pages are alive with strife.

Players can only retain seven coins/tokens from turn to turn. But there is a corresponding freedom in spending that forcefully encourages creativity and combination. Get as many coins and Ritual tokens as possible, buy cards and use them immediately, spend between tile placements, take chances, create opportunities. The freedom is overwhelming in that first play, but I’ve really enjoyed trying new things as I’ve gathered familiarity.

My two Alf Seegert experiences have taught me that there is an Alf Seegert experience. The Road to Canterbury and Illumination are spiritual cousins of sorts and it shows. I adore them both for every wink and nod within. I will continue to introduce them around to see if I can’t find like-minded players. In the meantime, I may have to get to know the mystic monk if I want to illustrate these old texts.

It’s good to see Illumination get this attention. It is a uniquely interesting game. I am biased because my son was responsible for the art in the project. Yes, it is quirky, but it absolutely reflects the spirit of the game and creates the atmosphere that you so much enjoy.

Illumination is definitely a gem, and the artwork is so very endearing. You should be proud! I do hope folks are willing to give it a try.