Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I apologize in advance for all the shouting.

HUANG

I went into HUANG already knowing it would be great. This is a new edition of designer Reiner Knizia’s Yellow & Yangtze, which was first released back in 2018. It’s a tile-laying game that depicts the rise and fall of rival states during the Warring States period in Ancient China, and it is fantastic. It helps that Yellow & Yangtze is playing with house money: it’s an iteration on—and in many ways a refinement of—Knizia’s crowning glory, 1997’s Tigris & Euphrates.

For HUANG, publisher PHALANX made the wise choice to leave the core game untouched. While the differences between Tigris & Euphrates and Yellow & Yangtze are significant, the non-aesthetic differences between Yellow & Yangtze and HUANG are non-existent. This is exactly the same game, renamed and repackaged. It’s barely even renamed; Huang is the Mandarin name for the Yellow River.

PAGODAS

Why PHALANX chose to cut the Yangtze out of the title, I don’t know. It’s still there on the board, long and wet, just like we left it. I suppose HUANG HE JIANG is not an inviting title for many people. Whatever the reason, the fertile ground surrounding these rivers plays host to the rise and fall of countless States, all built and destroyed one tile at a time.

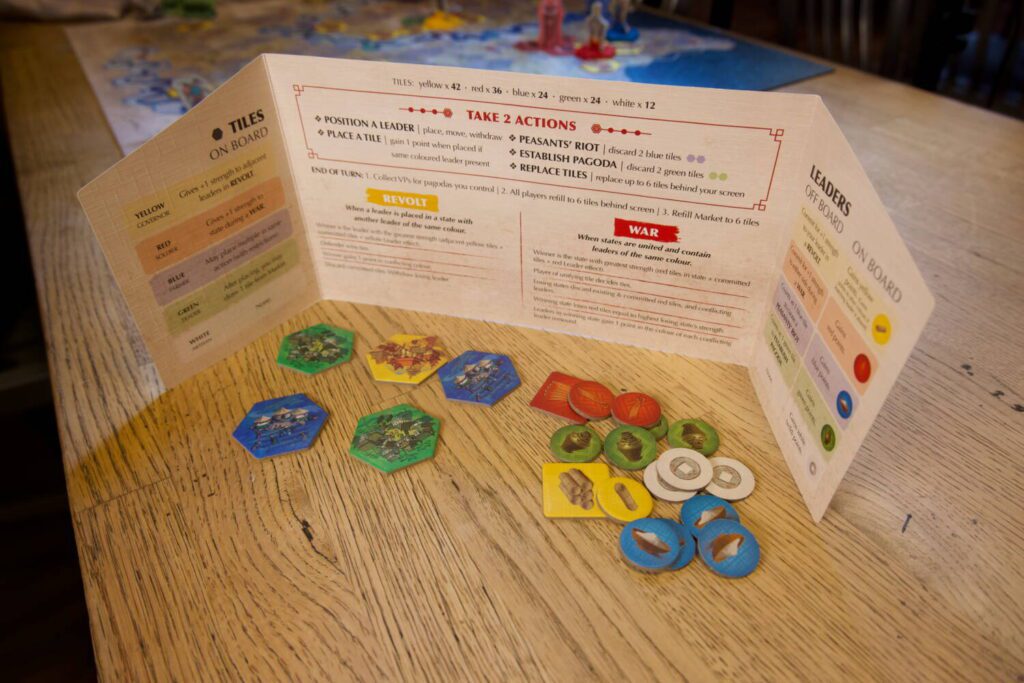

The tiles come in five colors, each representing one of the major contributors to any functioning civilization. There are blue farmers, red soldiers, green merchants, yellow political functionaries, and white artisans. With the two actions you have every turn, you can place tiles from behind your player screen out onto the board, you can discard tiles to draw replacements, or you can deploy your Leaders, which come in a matching array of five hues. The tiles only score you points if you place them in a State with the corresponding leader. If I place a yellow tile into a State with my yellow leader, I immediately nab a yellow point.

Tiles aren’t done when you place them, though, they continue to matter. If I place the third tile in a triangle of a single color, I construct a Pagoda at the intersection of the three pieces. The equivalent of Tigris & Euphrates’s mighty Temples, Pagodas you control give you an extra point in the matching color at the end of every turn. In Tigris & Euphrates, Temples are both hard to build and hard to hold onto. The point economy in that game is so tight that people will rightfully fight tooth and nail over control of those buildings. Their construction can fundamentally alter the arc of a game. Not so much with the Pagodas in HUANG, which are easy to build and just as easy to destroy. There are two in each color. If I create the real-estate conditions for a third, I snatch away one of the others and place it in my new position.

This is much of the real game of HUANG, tactically grabbing pagodas and preventing other players from getting hold of them. HUANG preserves the scoring mechanism that made Tigris & Euphrates so famous, that your final score is the color in which you have the fewest points, so managing to keep possession of one or even both pagodas in a given color for even a handful of turns can position you to never have to think about that color again.

CONFLICT

A game in this family simply wouldn’t be what it is without conflict. Every move you make in HUANG is rooted in conflict, really, but the game recognizes two direct forms of the stuff: Revolts and Wars.

Revolts occur when two Leaders of the same color attempt to occupy the same State. Everybody loves a coup. If I place my red Leader in a State where yours is already present, they tussle. Here is where the yellow tiles, those political functionaries, come into play. No Leader can be present on the board without at least one adjacent yellow tile, and yellow tiles are also the currency of Revolts.

Each Leader’s strength is determined by their adjacent yellow tiles, plus any yellow tiles either player wants to add from behind their screen. While HUANG’s board suggests determinism, there is almost always risk in taking a swing at someone else, especially when you consider that the aggressor has to commit any extra tiles first and the defender breaks ties. The winner of the Revolt maintains their position in the State, and takes a point in their color.

Wars center the red soldier tiles, sensibly enough. When two or more States—it’s so fun when it’s “or more”—join, provided there are any redundant leaders amongst them, those leaders go to War. The red tiles in each state add to their strength, and then, in a wonderful variation on the rules of Tigris & Euphrates, every player at the table has the opportunity to add soldiers to one side of the conflict or the other. This adds a delicious schmear politik to the proceedings. Players who have no direct stake in the War may still have preferences for how it plays out. The losing side removes all their red tiles from the board, in addition to any leaders. What was a cohesive State may now be a series of Statelets, disparate and up for grabs. The winner, too, has to remove soldiers in proportion to the number of soldiers they removed from the board. Wars in Yellow & Yangtze are wondrous climaxes, full of drama, simple in their execution but complex in their ramifications.

This does bring me to my one complaint: HUANG sacrifices a good deal of board legibility in the name of looking good. While the board, which resembles an old Chinese screen painting, is beautiful, it is busy enough that a quick glance is no longer enough to know what’s going on. You can miss things. This is especially true of the Leaders, which are represented here by cardboard standees on colored bases. Tigris & Euphrates and Yellow & Yangtze used wooden tokens, each embossed with the player’s insignia in the correct color. While the colors of the leaders in HUANG are easy to grok, it takes longer to process which leader, exactly, you’re looking at. In a game like HUANG, that information is vital.

MODERNITY

In returning to Yellow & Yangtze via HUANG, I came to further appreciate the changes Knizia made to one of his most important designs. I will always prefer Tigris & Euphrates, but I love it for the same reasons many people wouldn’t. It is a meaner, less forgiving game, in just about every sense. Yellow & Yangtze/HUANG takes some of those edges off by learning the lessons of games designed in the 25 or 30 years between. Knizia added a tile market, accessible every time a player plays a green tile, which gives players a bit more control over the contours of their hands. Two blue tiles can be discarded at any time to stage a Peasants’ Revolt, removing a single tile from the board in a game where a single tile can be much more than that. The Leaders, when not on the board, function as an extra tile in their color for the purposes of Revolts of both kinds, Wars, and so on. It becomes, in certain circumstances, a strategic decision to leave your Leader off the board. There’s a lot of juice to be squeezed from a comparison of Tigris & Euphrates and Yellow & Yangtze, but let this suffice for the moment: Knizia smoothed the corners without sacrificing much in the way of depth.

About three years ago, there was a surge in appreciation for Knizia as a designer, which has carried through to the present moment. Affection for Knizia became so commonplace, so ardent, that an entire school of board gamer practically identifies as Knizian. His name is a Shibboleth. Given the breadth, depth, and impact of his output, we were always going to return to him eventually, but in considering HUANG I think I understand why we returned to him when we did.

The broader 2021-22 revival of Knizia as a cultural figure, the establishment of him as almost a cult of ludographic personality, is tied inextricably to the death of the mechanically straightforward but strategically deep Euro. For some time now, The Hobby™ at large has prioritized the complicated over the complex, the opulent over the rich. We want systems on top of systems, hats on top of hats, games that promise variety and “replayability” not through their quality and thoughtfulness, but their breadth.

Most games from Reiner Knizia are a rebuke to that ethos. He gives you very little, only what you need, and the rest is in your hands. HUANG does not take long to teach, nor does it require much time to grow comfortable. But spend some time with it, and you will discover the trademarks of every great Knizia design. PHALANX was right to leave the source material untouched. Yellow & Yangtze was, and HUANG is, an excellent tile-laying game.

Add Comment