Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

There’s this scene in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off where Ferris, his girlfriend Sloane, and best friend Cameron are standing in the sky deck at the top of the Sears Tower in downtown Chicago with their foreheads pressed up against the glass. Sloane comments, “The city looks so peaceful from up here” to which Ferris retorts, “Anything is peaceful from 1,353 feet”. Cameron then comments “I think I see my dad.”

It’s a total throwaway scene that lasts for less than a minute. It serves no purpose in the movie other than to let the viewer know that we’re definitely in Chicago and also that Ferris Bueller is a super cool dude. Eleven years after the movie was released I found myself standing in that very spot next to a security guard who’d been kind enough to escort me up there. Our foreheads pressed against the glass we fired off the dialogue from the movie before geeking out over everything Ferris Bueller. All in all, it was just 10 minutes of my life, but it was a really good 10 minutes. I realized something while I was up there. Ferris Bueller was right. Everything does look peaceful from 1,353 feet and he was right about another thing, life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.

While I was up there staring down at the city below, it got me thinking about a city’s identity. Every city’s got something it’s well known for that makes it unique, but there’s one commonality that all cities share – the skyline. That majestic silhouette of giant buildings that are situated just so, like carefully written letters in a signature. No two skylines are alike. Each one tells a story.

Overview

High Rise tells the story of a nameless city and the moguls developing it. When the story begins our nameless city is flat and boring. There is nothing special or unique about it. But over the course of three decades, towering monoliths begin to appear. By the end of the third decade the sky is filled with these graceful giants and the most successful developer wins.

The game is played using a time track. The player at the back of the pack will always take the next turn skipping from one zone in a neighborhood to the next, taking the actions on the spaces where they choose to land along the way, until they are no longer the last player in line. Then it’s the turn of the player who is now at the end of the line. This hopscotching continues until the players reach the stop zone where they must immediately conclude their turns. Once all players have stopped, an end-of-round scoring is performed in which the players with the tallest buildings will be awarded victory points (VP).

Many of the actions the players will take along the way are going to involve the collection of floor tiles. These floor tiles are the building blocks of the skyscrapers. The taller the skyscraper, the more points the players will earn when they construct them. But there are plenty of points to be lost, too, due to a little thing called corruption.

Most of the actions in the game can be supercharged by taking on corruption. For instance, an action that allows you to draw a tile may allow you to draw a second one provided you’re willing to become a bit more corrupt in order to do it. And while taking on some corruption definitely has its benefits, it’s going to cost you points at the end of the game. The more corrupt you’ve become, the greater the point loss will be. So, finding a balance between acquiring corruption and accumulating points is key to doing well in the game.

Of course, this is a high level overview of High Rise. Feel free to skip ahead to the Thoughts section if you think you’ve heard enough. Otherwise, keep on reading and I’ll tell you how the game is played.

Setup

The setup for a game of High Rise varies based on the player count and also the game mode that you elect to play: introductory, standard, or full. The player count dictates which side of the game board you use and also whether or not some of the spaces get blocked off. The game mode setups are largely similar except that in the introductory and standard modes the players start off with a building already in play and some resources in hand. The introductory mode also requires the players to play with a suggested set of tenants (this and other unfamiliar terms will be described in more detail later on) whereas standard utilizes a randomized selection of the same. In general, though, the setup for a game of High Rise is performed thusly:

The game board is set in the middle of the table. Then the tenant tiles are arranged by neighborhood, shuffled, and 3 are randomly selected and placed into each neighborhood’s tenant slots. Any Power cards associated with the tenant tiles are placed alongside the board in front of their matching tenants. Then the bonus tiles for the current decade are shuffled face down, drawn, and placed face up into the bonus tile locations. Some of these bonus tiles will dictate that floor tiles and/or UltraPlastic (UP) be placed on top of them. Some will call for specific Power cards to be placed next to the bonus tile locations. Any leftover tenant and bonus tiles will not be used and can be put back into the box.

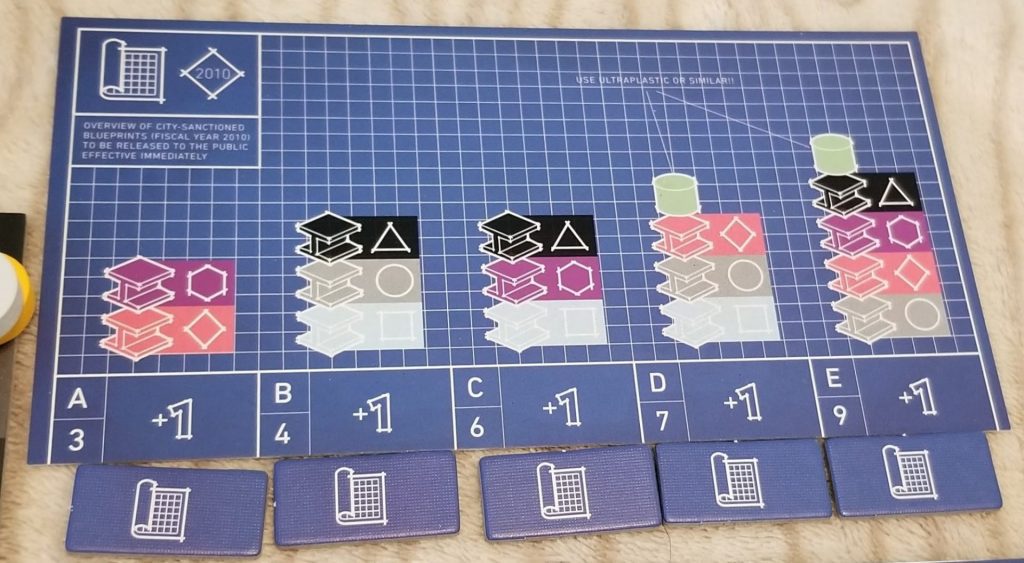

Next, one blueprint card is drawn for each decade. The card for the current decade is placed next to the card for the upcoming decade. In the full game, the card for 2030 (the final decade) is kept face down. The blueprint blocker tiles are set beneath the current decade’s blueprint card. These blueprint cards dictate the particulars of which buildings can be constructed during the current decade (height, floor tile make up, and whether or not UP is called for in the design).

Each player receives a starting construction yard (read: player board) along with the plastic building bases and wooden player markers of their chosen color. One marker is placed onto the 0 space of the corruption track and the other is placed onto the 0 space of the score track. The third player marker will be used to track the player’s movement around the central game board. The floor tiles are put into the drawstring bag and all of the other stuff – skyscraper standees, UP tiles, bonus tiles for upcoming decades, etc. – are left in a supply close by.

The person with the #1 printed on their construction yard will be the first player and their player marker is placed into the furthest left space of the stop zone. The second player will have the #2 printed on their construction yard and place their marker to the right of player 1’s. The other players follow suit. Once everyone has placed their markers into their starting locations, you are ready to begin.

[Of Note: High Rise includes a solitaire mode (which I will not detail in this review) as well as a two-player mode both of which use a dummy player. Each of these changes some of the rules in significant ways, which I will outline in future call outs such as this one.]

An Overhead View of the City

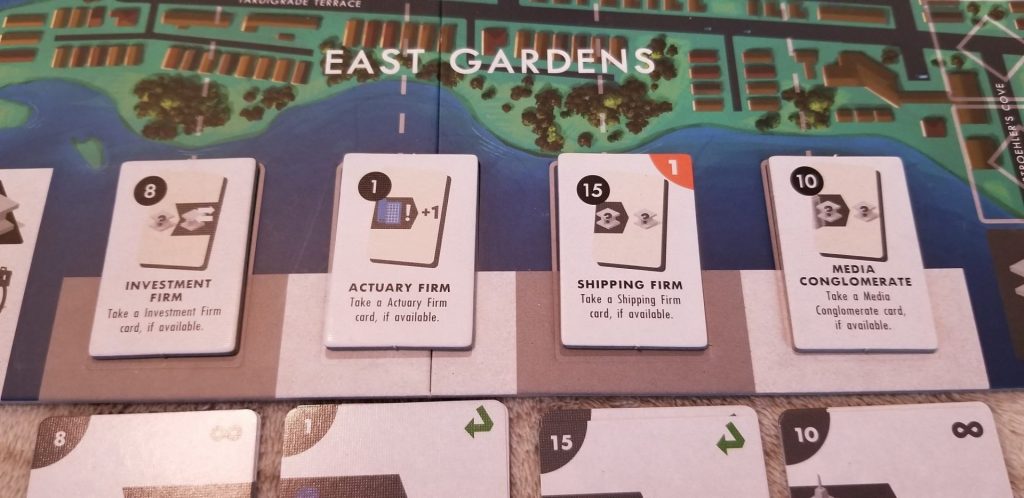

Our nameless city is divided into five different neighborhoods: East Gardens, Harbourside, Downtown, Bayside Heights, and City Center. Each of these neighborhoods are divided into several clusters of actions, called ‘zones’. In between each neighborhood is a bonus space that will have been populated with bonus tiles during setup.

On a player’s turn they will move their marker from one zone to any other zone on the board. If they pass a bonus space along the way, they will select one of the available bonuses to take and the corresponding bonus tile is removed. (A player may never occupy the same action space as another player.) The player then performs the action associated with the space on which they’ve landed. If that action space is a tenant and a player has built a structure there, the owner of that structure gets to draw a random floor tile from the bag. After the player has performed their action, if they are still the last player in line, they move their marker to a different zone and perform the action. Again, this continues until they are no longer the last person in line at which point the last person in line then takes their turn. The only caveat to this is that a player must stop in the first available space once they reach the ‘stop zone’ and cannot take another turn until all players have stopped and end-of-decade (a.k.a. ‘end-of-round’) scoring and cleanup have been performed.

[In the two player game, a ‘neutral mogul’ is introduced. The control of this neutral mogul passes from one player to the next after it is used, and it can be used for one of two things: move it to the first available action space in the zone in front of the lead player (called ‘blocking’) or move it into any legal space in the current or the next neighborhood and perform the associated action (called ‘moving’). Moving will cause you to take on an extra corruption and if the action performed causes you to take on even more corruption, you lose a victory point as well.

Also, in a two player game, once one bonus has been taken, the unselected bonus tile and its accouterments are removed.]

Buildings, Tenants, and Corruption – The Building Blocks of a City

Each of the neighborhoods in High Rise have 3 associated tenant locations and these locations are seeded with random tenants during setup. Whenever a player lands on one of these, they perform the associated action. Many of these tenant actions are related to gaining cards that provide various benefits such as allowing you to exhaust them to gain extra stuff when performing certain actions or cash them in to score extra points when constructing buildings.

Each tenant location is directly connected to a building spot. When a player constructs a building in one of these spots they automatically get to take the tenant action associated with that spot. With the exception of tenant powers that allow you to construct buildings, the only way to do so is by moving your marker to one of the construction zones.

When constructing a building there are several things to consider:

- Whether or not you have the collection of floor tiles and/or UP to construct one of the buildings on the current decade’s blueprint card

- Whether or not you wish to build in the current neighborhood or gain a corruption to build in any neighborhood of your choice

- If building in the same neighborhood: is the neighborhood full? If so, is your building taller than the shortest building? If it isn’t, it can’t be built there. You’ll score points for it, but won’t be able to place a building onto the board. If it is taller, the shortest building gets demolished (removed from the game) and its owner receives 2 random floor tiles from the bag.

Each decade’s blueprint card shows a number of different blueprints depicting buildings that can be constructed that decade. Each blueprint displays a stack of different colored floor tiles and some may depict one or two UP on top of this stack. To build, the player trades in the appropriate floor tiles and UP then takes one of the building standees of matching size, attaches their base to it, and places it into whichever location they have decided to build. Bonus floors can be gained by making sure you use UP where it’s called for, being the first one to build a certain blueprint, and also through some Power card interactions. Tacking on as many bonus floors as you can is important because in addition to placing the building onto the board and using the tenant’s power, you also score points equal to the number of floors you have constructed.

It is also worth noting that UP is a wild resource and can stand in for any colored floor tile and any colored floor tile can stand in for it. So, if your building calls for a UP as the top floor and you don’t have one, you can stick some other colored floor tile up there and still construct the building. You just won’t get a bonus floor out of the deal.

As your city grows, so will your level of corruption. While it is technically possible to play High Rise without gaining any corruption, it is doubtful you will do very well. The trick is figuring out how to balance your corruption gain with high-scoring opportunities because, as mentioned previously, being corrupt at the end of the game is going to cost you points. The more corrupt you are, the more points you’ll lose. There are a few locations along the board that will allow you to move backwards on the corruption track, but not very many. As such, these locations typically get used up pretty fast.

Measuring Up

At the end of each decade a scoring is performed in which the tallest buildings (both the tallest in the game and the tallest in each neighborhood) are scored. At the end of the first decade, 2010, only the first tallest buildings get scored and they’ll earn their owners 1 point each. At the end of 2020, the first and second tallest are scored earning their owners 2 points and 1 point respectively. And at the end of 2030, the first, second, and third are all scored earning 3, 2, and 1 points respectively. High Rise is a game with friendly ties, so if two or more people tie for any position, then they all score the full amount of points. It is even possible for a person to tie with themselves, gaining them twice (or even thrice!) as many points.

To better illustrate this, let’s consider an example:

It is the end of 2030 and the red player has 3 buildings in Bayside Heights each measuring 7 stories in height. Since nobody else has taller buildings there, the red player has the tallest building and, since they are all of the same height, they tie themselves for having the tallest, scoring 3 points per building.

After scoring the tallest buildings, an upkeep phase is performed in which any exhausted Power cards are refreshed and player corruption is adjusted. At the end of the first 2 decades, the person with the fewest VP moves backwards on the corruption track 2 spaces and the person with the second fewest moves backwards by 1. Then the person with the most corruption takes a penalty which differs depending on the game mode: they’ll either lose some VP or have to flip over a Power card making it unusable in the upcoming decade.

[In a two player game, the player corruption is adjusted differently. At the end of 2010 and 2020, when adjusting player Corruption, if the difference between the two players’ scores is 5 VP or fewer, the player with fewer VP moves backwards 1 space on the corruption track. Otherwise, the player with fewest VP moves backwards 2. The player with the most VP doesn’t move. If the players are tied, neither player moves backwards on the track at all. The corruption penalty from the full game mode is applied, but neither player flips a Power card if they are tied.]

The scoring is slightly different at the end of 2030. In addition to scoring for the tallest buildings, players will earn VP for their leftover floor tiles and then lose VP equal to the number printed on the corruption track space their marker currently occupies. The person with the most corruption loses an additional 3 VP and the player with the second most loses an additional 1. Once the scoring for 2030 is complete, the player with the most VP wins.

Thoughts

There’s a lot to like about High Rise. For starters, it’s a very attractive game. Heiko Günther’s graphic design and Kwanchai Moriya’s gorgeous artwork combine to present a very eye-catching experience. This is a game that has a strong table presence, especially in the later stages when the board is dotted with skyscraper standees. However, it isn’t perfect. A while ago, I reviewed a game called Rhein: River Trade and one of my critiques about that game was that there was a lot of negative space. The same is true for High Rise. The various zones around the board are alternating greys and whites and that lack of color definitely detracts from the overall aesthetic. I wish that more care had been taken to make these functional spaces less austere in appearance. I also wish the tenant tiles and their associated cards were treated the same. They’re all functional, but very boring to look at.

That’s just me being nitpicky, though. The artwork and graphic design aside, High Rise is a very good game. I love me a good time track. Used in games like Glen More and Nova Luna, the time track mechanic presents a lot of interesting options to a player on their turn. Should they leap way ahead to grab up a hotly contested action location before someone else does or should they take it slow in the hopes that they’ll be able to take several turns in a row? It’s a mechanic that forces you to weigh efficiency versus immediacy, quantity versus quality.

Then there’s the question of which actions you should actually take. The glut of your points in High Rise come from building so, ideally, every action you take will be in service of this goal. With all of the floor tile drawing actions, you are at the mercy of the random draw. Taking on corruption can help improve your odds, but then you have to weigh that against the VP loss at the end of the game. Is it worth the gamble? Do you see future action spaces available that will let you mitigate less than ideal bag draws? Are you going for the tallest building you can construct or should you settle for something smaller and more easily attainable? Do you build in the same neighborhood or maybe take on some corruption to build in another to not only use the tenant action, but to set yourself up for a better position during scoring and maybe even a random tile draw if someone decides to land on that spot?

These are just a few of the different things you’ll find yourself considering at every turn. These decisions become especially interesting in the two player game where being able to manipulate the dummy player can effectively set you up for a very successful turn or several turns in a row. It reminds me of Five Tribes in this respect. For instance, you might want to use the dummy player to build a building to net you some points and utilize the tenant action and then follow that up by moving your own marker onto that space to utilize the tenant action a second time and net yourself a random tile draw in the process. It’s a pretty heady game once you’ve wrapped your head around the mechanics.

That brings me to my only other negatives about High Rise: certain aspects of the rules. There are a lot of details in the rules that a player is expected to remember — details that seem relatively small but end up having large impacts on the game. There is a player aid included and it does an alright job of reminding you of the basics, but it skimps on the details. In my opinion, it would have been useful to have a secondary player aid that listed off all of the various actions in the game that would result in a player having to take on corruption at various player counts — because there are a lot of them. It would have saved me a lot of consternation along the way.

There are also a lot of side cases that the rules simply do not address. For instance, the concept of neighborhoods is very important in this game (especially at the one and two player count), but the rule book never actually defines just what exactly constitutes a neighborhood. It took me reading the extensive F.A.Q. on BoardGameGeek to find the answer to this. Hopefully this and all of the items in that F.A.Q. will be addressed in future editions of the game (provided there are any). It’s just a fact of life at this point that some Kickstarters feel like more ‘playtesting’ of the rule book should have been performed before the game was ever published. The rule book for High Rise is no different. Don’t get me wrong. It is a very good rule book, but it could be much, much better.

In closing, is High Rise a perfect game? No, not by any means. But it does come pretty close. The mechanics of the game keep it chugging along smoothly and there is a lot of strategic decision-making along the way. The artwork is brilliant and the 3D aspect of the skyscrapers really helps to sell the narrative. High Rise is not a great game for people who are new to the hobby, but for those looking for a good challenge, it definitely rises to the occasion.

Add Comment