Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Mertwig’s Maze is an Advanced Dungeons and Dragons game that was released all the way back in 1988. Everything you need is in a folio that contains the game’s rules, maps, dungeons, and small cards that represent all of the game’s stuff: characters, enemies, items, treasure.

I love Mertwig’s. I love it so much that once a year, I break it out with the same guys I gamed with as a kid. Sure, I also played regular Dungeons & Dragons (or “D&D”, for short), but Mertwig’s was perfect as a self-contained adventure that had all of the stuff you needed for an afternoon of pure glee.

Someone recently asked me a question that I struggled with: “I know you love Mertwig’s. But is Mertwig’s any good by today’s standards?”

After spending some time waffling, the answer has become clear. Mertwig’s Maze is not a great game by today’s standards. The ending is legitimately broken, with a silly dungeon dive into a maze underneath a castle to win. Some of the spells are comically overpowered. Rolling a die to move into the game’s main forest means that some players will fall behind purely because they can’t start their looting as fast as other players.

In other words, it has real design problems. I don’t care. I love playing Mertwig’s because I love the memories of playing Mertwig’s as a child.

HeroQuest (1989, Milton Bradley) is older than many of our readers. But Hasbro/Avalon Hill recently re-released the game, giving new players a chance to experience a game that, in Milton Bradley’s own words, is meant to be an RPG-like system in the same vein as game systems such as Dungeons & Dragons.

Now that I’ve played HeroQuest multiple times—please note that I did not play this game as a child—I believe that HeroQuest hasn’t aged very well. But for players looking for HeroQuest, the game hasn’t changed at all by all of the accounts I have found on the interwebs. For many players, that is all they needed to hear; for other players who haven’t played HeroQuest before, I think you can get your dungeon dive on elsewhere.

Zargon, The Punching Bag

HeroQuest pits four heroes—a barbarian, an elf, a wizard and a dwarf—against Zargon, an evil sorcerer who serves as the game’s controller. Zargon is the game’s “Dungeon Master” (DM) and must be played by a human player. Zargon controls all of the game’s bad guys, known as the Forces of Dread; that means that any goblin, orc, skeleton, or other evil force is run by Zargon.

However, Zargon’s role is much easier to administer than a DM in a D&D game. Zargon reads a short paragraph to kick off each session, places pieces on the board, and rolls dice. No storytelling skills required.

This is important because many people, myself included, bristle at the idea of serving as a full-time storyteller for a bunch of people sitting in a circle in a hotel lobby who have come to hear me weave a magical tale purely of my imagination. I like to write, but I don’t like to tell, if that makes sense. And keeping a game world going for a five-hour sit with friends? That’s a big ask for someone like me.

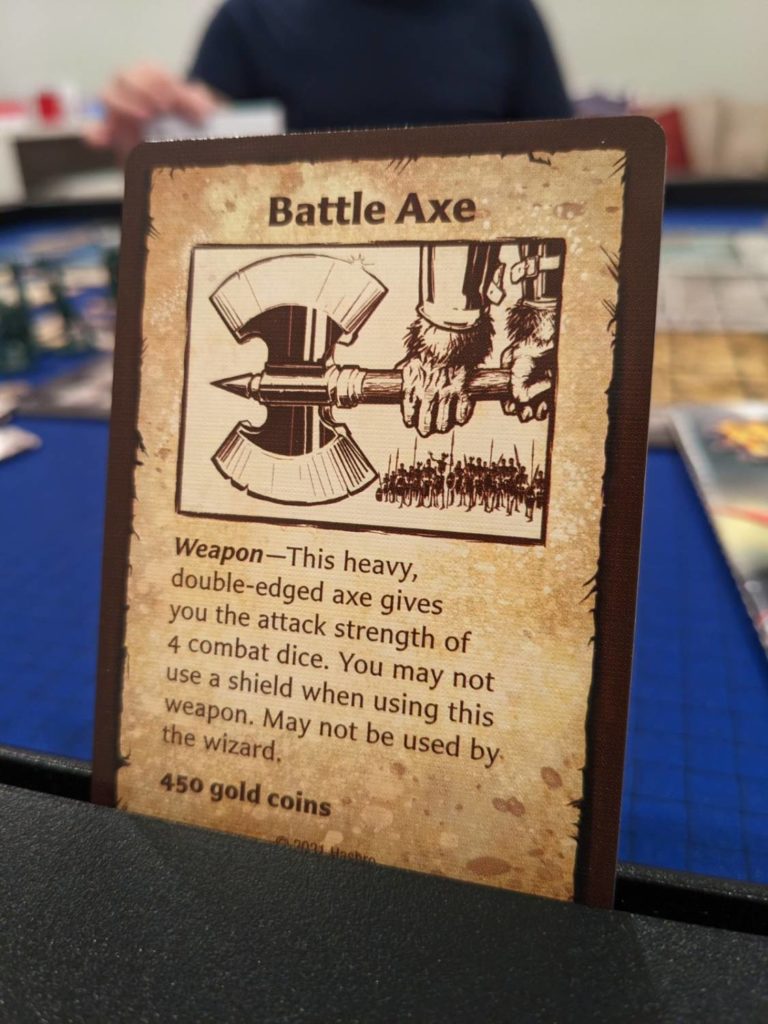

HeroQuest differs from Dungeons & Dragons in additional ways—there’s a physical board with 3-D miniatures and furniture, but the characters also have a streamlined profile. A small sheet of paper tracks hit points (known as Body Points in HeroQuest), weapons, items, treasure, and mind points. Characters in HeroQuest don’t have skills or attributes (such as Dexterity, Cunning, etc.); they just have a character card, and a starting weapon.

Over the course of 14 sequential gaming sessions known as Quests, the four heroes will try to run the table. In some Quests, that just means killing every monster on the map. In some Quests, there’s an escort mission (of either treasure, or a non-playable character); in another Quest, it’s a game-long bounty hunt with coins awarded for every kill.

The best thing about HeroQuest is the variety of different Quests designed by Stephen Baker and his team. Using a single game board and a Quest Book that rearranges where all of the monsters are hidden in each mission, HeroQuest does quite a bit with not a lot; it feels like a world, even if that world gets a little stale even after just a few missions.

Each Quest starts the same way, with the four heroes standing on the staircase that led to the floor of the current mission. Then, Zargon reads some flavor text to set the stage for that mission, before players work together to beat that Quest. A hero turn runs simply: move, then take a single action, or take a single action, then move.

Movement is dice-driven; roll two six-sided dice, then move up to the number of spaces rolled in any direction. Actions include attack, search (for traps, treasure, and hidden doors), cast a spell, or disarm a trap. While most players will spend their actions attacking enemies, the search actions give HeroQuest a minor amount of tension as players wait to hear from Zargon whether their searches have come up aces or ended with someone getting speared by a trap from a nearby treasure chest.

After all of the heroes have taken their turn, Zargon manipulates the bad guys, if any are currently on the map. This led me to refer to Zargon as a punching bag because the role is so thankless at times. New rooms have to be discovered, whenever a wandering player opens a door to peek into a new space. Zargon places new monsters and furniture in a room while waiting for the heroes to explore it.

Even though Zargon rolls the dice for all of the bad guys, this quickly becomes less interesting than it sounds. Zargon becomes a punching bag as the barbarian smokes all of the lower-level goblins or orcs in a room, or as the magic-user heroes (the wizard and elf) cast spells that neuter all of the things a bad guy can do on a turn. This gets marginally more interesting at the campaign midpoint, but still, Zargon’s chances of winning are often not great.

In a Vacuum

If one were to completely isolate HeroQuest as a point in time (that time being 1989), the gameplay here is excellent, particularly if you are playing as a hero.

Compared to some of the games I played growing up, HeroQuest provides an RPG gateway experience that qualifies as big, dumb fun. You chuck dice. You enter rooms, then someone else serves as a custodian for setting the stage to chuck more dice. The Quest Book does so much with a simple set of rules; some of the HeroQuest missions are plain wacky, like one that assumes a portal system based on die rolls where you pop into a room only to be faced with killing off a zombie or two, while waiting to see if another player appears in the same room when they land on your head, damaging another player.

HeroQuest is pretty easy to teach, even for a game from 30 years ago that is generally light on rules. The rulebook for the 2021 re-release of the game is longer, about 25 pages, but most of the concepts are listed on just a few of those pages. The miniatures are fantastic and understanding how to work with teammates is a joy.

HeroQuest hits a stone wall, though, when one compares it to almost any of the RPG-like games of modern times.

Let’s start with the Zargon role. Dozens of games have replaced human DMs with app-driven programs that do almost all of the work Zargon would do in this game. That really hurts the experience. For example, I’ve played Return to Dark Tower, Mansions of Madness 2E, Destinies, and other games that do all of the Zargon-like work for you.

That means that if you’ve played any of those newer games, you immediately feel worthless as a DM. When a hero announces that they want to see a new room, Zargon replaces that room’s closed door miniature for an open door miniature, they place a throne and a weapon rack in the room for scenery before adding a gargoyle, zombie, and two goblins. Then the players beat the heck out of the majority of the bad guys. (My favorite insult to injury: when the barbarian draws his longsword and rolls three white combat dice, coming up with all hits, knowing that the goblin could have only rolled one defense die anyway).

On a shocking number of turns—either as a result of heroes rolling well, or no monsters being discovered early in a game—the Zargon character has literally nothing to do. Do you want to play this role for 14 #$%@#& games??

Now, imagine it’s the present day, because, well, it is. A game like Destinies does all of this work for you, so all you have to do is roll the dice to attack. Destinies (which also has exquisite minis, albeit less of them) is faster, cleaner, and easier to put away, without losing anything of what a game like HeroQuest gives you.

The DM in HeroQuest is not a storyteller; they are an administrator. If you are offered the chance to serve as Zargon in HeroQuest, you should almost certainly say no.

The Aging Process

A fan of the original HeroQuest game looking to HeroQuest again with more HeroQuesters has likely already purchased this game, and for good reason. By many accounts, this is the definitive version of the game. The production is incredible and the sculpts for these miniatures are ridiculously amazing. I really love that the undead character miniatures (such as skeletons or zombies) are white, while all other minions are dark green. And those cute little rats!!! The world-building is fantastic and will draw in players old and new to the experience.

But compared with games of the now, HeroQuest is in a tough spot. It doesn’t do anything special with its dice-based combat. (I strongly prefer games like Arcadia Quest to HeroQuest, for example.) The DM role of Zargon just isn’t that much fun. In 1989, it was OK to play a game with four standard-issue hero characters; gosh, in 2023, it feels crazy that you are basically using the same four archetypes as your hero set now.

An interesting note about those characters: HeroQuest is a game where all of the non-wizard characters feel a bit samey. Sure, the dwarf is better at disarming traps. Sure, the barbarian has more body points. But turn to turn, they don’t feel much different. The wizard mostly uses cool spells during their turn. The elf can use three spells to the wizard’s nine, and that is occasionally a thing. But it’s not the special sauce. For the most part, every turn features a hero moving, then attacking, or attacking to start their turn if they begin a turn in range of a baddie then moving. The juices just don’t flow here.

And don’t even get me started on the bad guys. In the base game, how many goblins does one have to kill to feel validated? The goblins and the orcs are dead so fast it almost hurts to set them up—the more advanced enemies are where it is at, but they don’t typically appear in the early stages of a Quest.

As an experienced gamer, it is safe to skip the first three Quests, maybe even the first four. Just start the Quest book on Quest four or five, draft an upgraded starting item, and give each hero maybe 150 gold pieces. You’ll also want to house-rule some of the rules around movement and the end-game condition. Technically, all of the heroes have to end on the starting staircase to win, but when it made sense, I told players that all of the bad guys were dead and we just called it a game.

I think this is best because the first few Quests are just too easy, which compounds the issue with the Zargon role. It’s essentially impossible to kill any of the heroes when you, as Zargon, are trying to take down the barbarian with a goblin or an orc. This makes Zargon an expensive puppetmaster who just doesn’t bring the heat.

A few other notes; let’s start with player count. With a full complement of five players (Zargon, plus one person playing one hero each), the game runs too long, as much as 75-90 minutes per session. Four human players will talk through too much to make simple decisions, so two-handing two heroes each for two human players is the way to go (this means playing HeroQuest as a three-player game).

Next up: price. HeroQuest does offer a gamer a ton of content, but $100 feels like a bit much. Sure, the minis are great, but are they $100+ great? When I told the members of my review crew the MSRP for HeroQuest, one of them looked like he was physically ill. In the new realm of gaming, where mini-heavy games regularly go for $200+, maybe this price is right. But it feels high for HeroQuest and others who joined me at the table agreed.

I very much wanted to enjoy HeroQuest, but was disappointed at how the game system has aged. Even the loot phase after each Quest is a challenge; everything is so expensive that you won’t be getting a sexy piece of chain mail for many, many moons. We’ll cover some of the expansion content at a later date, but there’s plenty of additional ways to spice things up, and maybe one of those expansions will become required reading.

After thinking about the best way to position HeroQuest for new players, here’s where I’m at: it’s great to be a father of two curious young children.

That’s because I can make HeroQuest an interesting experience for my 9-year-old daughter and 6-year-old son by removing some of the game elements and watching with glee as the kids explore the dungeon and wonder if they are about to wander into a trap. I can set up the game and administer the bad guys, giving me more time to keep them away from screens and almost certainly guarantee that the kids will win.

For a parent looking for a way to engage in this way, HeroQuest may have some legs. For a group of adults, I recommend dice chuckers like Arcadia Quest instead. In both cases, you are going to love the miniatures.

Absolutely awesome game, many happy memories playing heroquest back in the 90`s. Me & my mates couldn`t handle D&D but this totally worked. Questing with Dr.Feelgood the wizard, Gonad the barbarian & my mates dwarf Gudgulp the 18th … he got killed a lot because he had a bad habit of searching for treasure at the wrong time. ty Justin for this post.

Hi, I think you’re missing two important things from this game IMHO. Firstly, being Zargon so dumb to play allows the master to play both DM and one of the characters in the game. In my case, nobody wants to play as DM, so it is a good thing Zargon is so straight forward.

Secondly, I don’t see Heroquest as a RPG game but more as a hack and slay one; it is like comparing the PC games Baldur’s Gate with Diablo, where Heroquest would be Diablo.

Best regards,

Javier