Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I’ve been on a bit of a Reiner Knizia kick recently. A Knick, if you will. This year Meeple Mountain is publishing our Reiner Knizia alphabet, choosing one game for each letter and diving into the history, experience and culture around it. An initially small idea that grew out of hand, then stretched even further. By the end of 2025 – Knizia’s 40th anniversary of publishing games – I’ll have written around 25,000 words about Knizia and his games. A knovella.

Ask most people in the hobby to define Knizia’s games and their answers broadly run the same: simple rules, depth of gameplay, maths, weird scoring, interaction, abstraction.

True Kniziaphiles, however, will say something else. True Kniziaphiles will say drama, and will feel their heart quicken at the thought, their eyes sparkle with memories and a smile tug at the corners of their mouths.

Let’s talk about Havalandi and drama.

“My grandfather invented the cold air balloon… But it never really took off.” Milton Jones

Have you ever stumbled across a regatta of hot air balloons? I remember driving along early on a summer’s morning and it was as if another world was breaking through the blue, vibrant teardrops perforating the sky. There was something mesmerising about the scene, a skyful of colour hanging silently above the horizon, humanity’s closest approximation of a murmuration. Further along the road I caught a view of the launch fields. Some balloons were unrumpling and straining at their ropes. Some had only recently launched, tentatively rising upwards. Others floated high already, proud and regal. It was like seeing the chosen ascend.

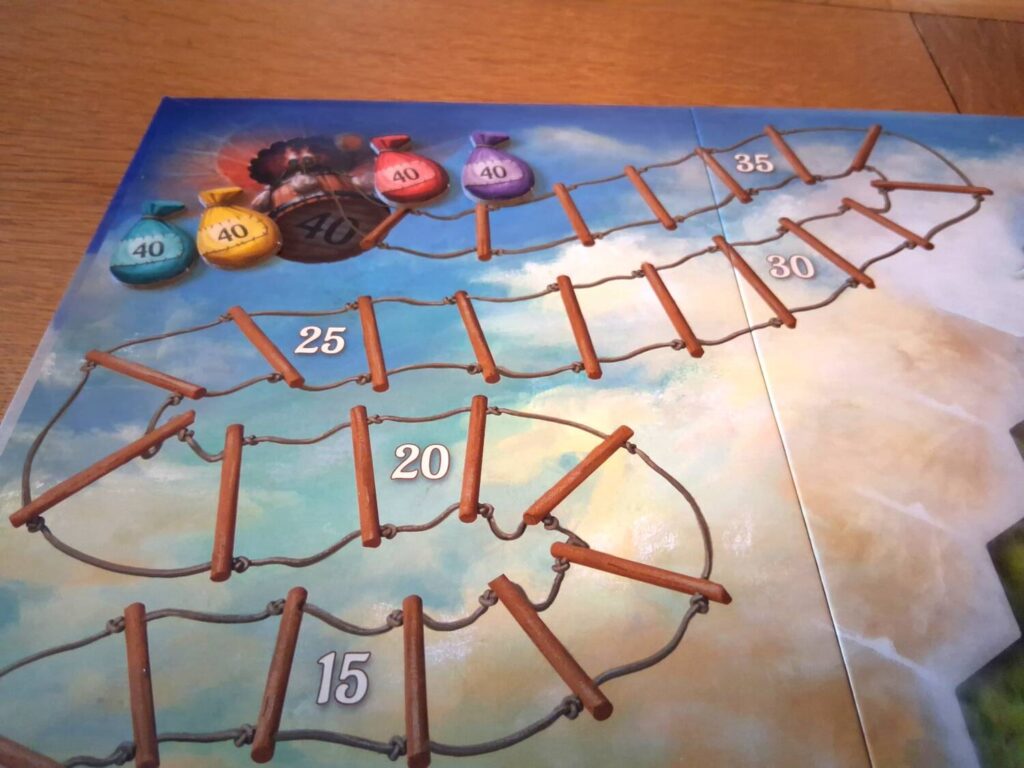

Havalandi, a 2023 Knizia release from publisher Pegasus Spiele, is about placing and launching hot air balloons from regions of tulip fields, sand dunes and meadows. Every turn you place a single balloon tile, aiming to launch fleets, create groups of balloons in regions, entertain pavilions or meet one of the two random end-game conditions. All in the name of points, climbing up a rope ladder score track to a balloon that jettisons score-counter sandbags when you reach the top and start your ascent again.

It’s a rather lovely affair.

The colours are glorious, the few illustrations are elegant, the pacing and gameplay almost frictionless. Tonally a lot is right with Havalandi. It’s just missing any sense of marvel, feeling small and inconsequential. It lacks the quiet majesty of seeing a skyful of hot air balloons. It lacks the wonder and the joy and the spectacle. It lacks drama.

I’m being harsh here. Havalandi is a good game, a very pleasant way to pass 40 minutes. It reveals its depths over multiple games and most turns present interesting choices. There are plenty of scoring opportunities to occupy the mind and it’s a tight enough board that players end up crowding together which keeps things interesting. Elbows aren’t out and there’s no shoving (as you might find in a Knizia tile-laying game such as Through The Desert), but you can feel the press of the other players.

There are, however, a couple of tears in the balloon’s envelope that may worry some aeronauts.

“Rules are for the obedience of fools and the guidance of wise men” Douglas Bader

Tear one is a minor flaw but, in truth, it’s major: the rulebook. It’s abysmal. The worst rulebook I’ve read in a long time, including last year’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Havalandi is a relatively simple game. I can teach it to new players in under 5 minutes and there won’t be many questions during the game itself. But I only know how to play thanks to a condensed rules sheet that some generous soul shared on BoardGameGeek. Had I relied on the rulebook alone my first game would have been awful. The rules as written bend and twist the straightforward gameplay to make Havalandi appear more convoluted than it really is.

It’s a minor flaw, since when you know how to play it’s not an issue, but it’s also a major flaw in that getting to that point is actively sabotaged. It’s doubly major since Havalandi is a game that gets better with repeat plays, but the rules try to put you off from ever returning.

“Everyone talks about rock these days; the problem is they forget about the roll.” Keith Richards

Tear two is a major flaw but, in truth, it’s minor: the die. At the start of each turn you roll a standard six-sided die and move the wonderfully large cardboard hot air balloon around the edge of the triangular board. The lines of sight where it stops are where you can place your balloon that turn. Initially this feels overly restrictive. In my first game I started creating a group in one area and then spent the rest of the game unable to do much with it thanks to unhelpful rolls of the die.

Frustrating you might think, that awful roll-and-move mechanism that everyone seems to hate rearing its head again, a rent in the balloon’s material. You’d be wrong though. Sure, the die plays its part but it’s not as restrictive as it appears. You can extend groups of balloons in regions stretching out from those lines of sight meaning you aren’t completely bound to it and there are also three special balloons that help you break beyond the game’s confines. The four separate ways to score pull you in multiple directions as well, so whilst you might not be able to do exactly what you want, you can almost always do something useful.

I like restrictions in games. I like making the most of what you’re dealt. It’s why only drawing one tile on your turn in Carcassonne is the game’s best rule. How do you utilise the tools you’ve been given to turn the game to your advantage? In Havalandi you work within your understanding of risk and probability. Not in terms of specific rolls of the die itself but considering how each balloon placement is useful right now or might be useful in the future. You may not be able to control that future exactly, but you can prepare for it and that’s where the tension in Havalandi comes from, balancing the certain nows against the high scoring what ifs.

Part of the problem is that Havalandi feels like it should be a certain type of game. This is Reiner Knizia we’re talking about; the man has made some of the best tile-laying strategy games of the past 40 years. Havalandi looks like it should follow in the same footsteps but instead you’re gambling with whether placements pay off or not. It’s push-your-luck tactics masquerading as deep strategy.

And therein lies the rub: it feels like you should have more control than the game allows whilst simultaneously you’re given more influence than you at first realise. Blame the die and Havalandi seems insubstantial and too luck-based. The die appears to be a major rip to Havalandi’s integrity, but it’s only a minor nick. Lean into the game’s intentions, embrace the restrictions, understand the intriguing board shape and patterns, and prepare for possible futures and Havalandi reveals its depths to you.

“Drama is life with the dull bits cut out” Alfred Hitchcock

I recently spent a weekend in the Yorkshire North Pennines with some friends. Between hill walking and excessive quantities of food and drink, we played plenty of board games, among them four Knizia designs. Three of them provided the kinds of memorable experiences that this hobby does best, moments of high triumph, crushing failure, startling comedy and clenching tension. I could regale you with the astonishing hurtle across the map on the final turn in The Quest for El Dorado. I could speak in hushed tones about the blocking and quiet hums of appreciation of a turn well taken as we lined up colours in Einfach Genial 3D. I could imitate the curses and tongue-clicking satisfactions that sounded as we jostled for oases in Through the Desert.

I can’t tell you anything about our game of Havalandi, except that we played it back-to-back with Through the Desert and it was the camels that got a second outing.

I don’t know whether it’s the die or the almost point-salady approach to scoring or the limited player interaction or some other aspect of Havalandi but unlike those other games, and much of Knizia’s back catalogue, it doesn’t bring the drama. There are highs and there are lows but they aren’t all that high and that aren’t all that low.

Havalandi is a rather lovely game, clever and entertaining but rarely all that exciting. A hot air balloon ride tethered to the ground: beautiful and peaceful and lacking spectacle.