Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Halls of Hegra is, admittedly, not a hard sell for me. It’s a quick-playing solo game with simple-but-challenging enemy AI, a heavy focus on emergent narratives, and an obscure WWII battle as source material. Check, check, and check. More than that, it’s an experiment in welding historical solo games to distinctively Euro-y mechanics. This is a straight worker placement game. Put me in, coach. I’m ready to play.

Somewhere in This Review I will Accidentally Refer to the Game as “Halls of Hegras,” I Am Sure of It

Halls of Hegra is a successful marriage of worker placement with a standard wargaming format. Place workers, execute commands, survive enemy fire, wash, rinse, repeat. There are a few things that separate it from similar designs.

Hegra Fortress, located in southern Norway, was never intended to be a part of World War II. It was buried in snow when the Norwegian army set up shop. Just as those men were tasked with digging out the base in advance of the Nazi assault, you benefit from focusing on snow removal in the early game. Many of the best action spaces on the board are buried in a stack of snow tiles, available only once revealed. You want real fire power? You’re going to need to dig out the heavy artillery.

It’s important to keep in mind, also, that my use of the word “army” in reference to the Norwegians is generous. The majority of the 250 troops at Hegra were volunteers, accumulated from the local population over several days in advance of the Nazi assault. Here, your troops are wooden discs, belonging to a variety of classes: volunteers, hunters, soldiers, and medics. The game replicates that slow and ramshackle drip of manpower (there was one woman at Hegra, the nurse Anne Margrethe Bang) through recruitment, which happens via a push-your-luck mechanism at the beginning of each of the early, preparatory rounds.

Here, before the battle starts, is your first point of tension. You can pull up to four tokens from the recruits bag, one at a time, but there’s a risk to continuing. Recruits don’t immediately go into your available pool. Instead, they wait until you decide you’re done drawing. If you happen to reveal any Doubt tokens from the bag, those awful bright pink indicators of your own failure to keep moral up with the locals, you lose out on all but one of the recruits you’ve drawn up to that point.

Not everyone is going to like the luck involved in that process, but those people probably shouldn’t be playing Halls of Hegra in the first place. This is a luck-heavy design. While your actions are not subject to dice, the enemy’s are, and the wrong rolls can send you screaming towards an early surrender. You draw a card with negative/adversarial effects every round, which helps to dictate the shape of things. Once the sieges start, those cards get brutal. “Swingy,” you might call them. This is very much a game you can lose at the last minute because of just the wrong draw. After 75-80 minutes of playtime, that will frustrate some people. For myself, that’s part of what makes it so narratively evocative. If everything works like clockwork, there’s not much of a story.

The bulk of each round is spent assigning your troops to the different action spaces and then executing those actions. You can shovel snow, run through the Norwegian forest for supplies, treat the wounded in the infirmary, repair damage to the base, or, if you’ve been good, shoot some Nazis. The breadth of actions is one of the more impressive things about Halls of Hegra. You have choices. Sometimes you have too many choices.

Add to that breadth of choice the niggling detail that is the various classes of workers specializing in different things. The soldiers are better at operating guns than the volunteers. The hunters make ready work of the snow and they’re much better at getting supplies. The medics, well, you can guess what they’re best at. You also have one commander, who has his own strengths. Assigning your troops each round is a satisfying little puzzle.

Siege the Day

After three rounds of peacefully getting ready, the attack begins. You’re under no false impression that you’re going to win this battle. You’re just trying to hold out. This is a game you win by losing as little as possible. The first attack isn’t so bad. The Germans retreat after three manageable days. Then the sieges start. The sieges, unlike the attack, seem to involve an unending deluge of enemy soldiers storming the base and firing at your defenders.

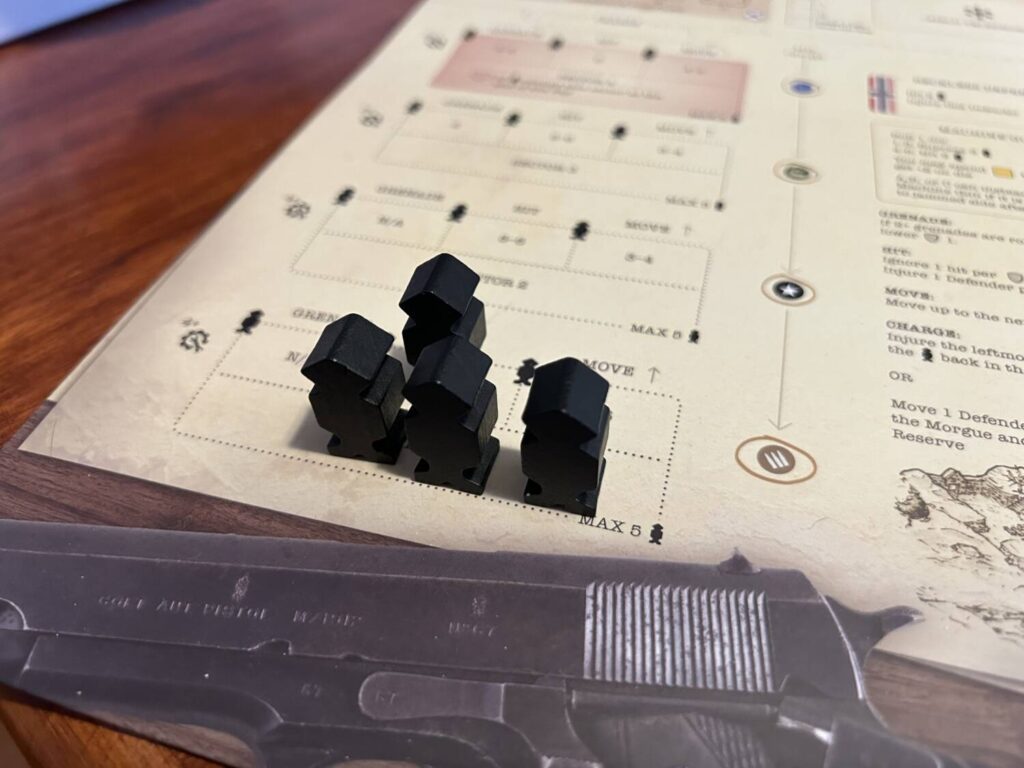

Halls of Hegra uses a smart, simple system to approximate the encroaching Nazi lines. You roll dice and advance the enemy soldiers up a series of ranks. Some fire. Some move closer. Some lob grenades. Some get confused and lie down. These are the enemies with whom I have the most in common.

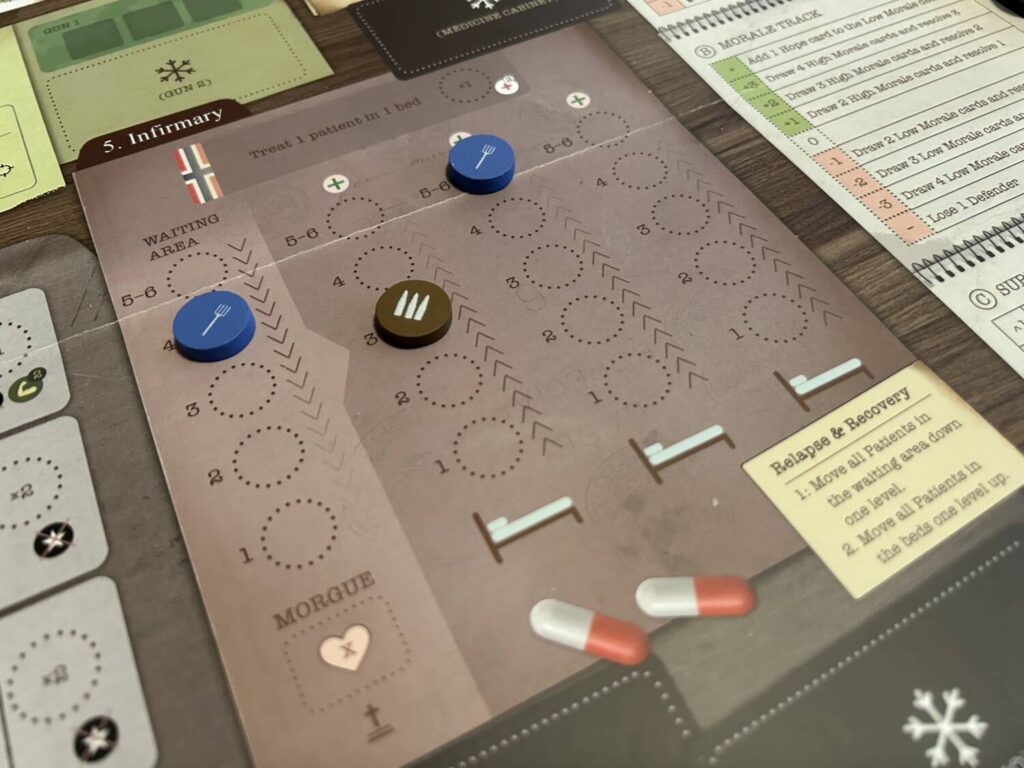

When you take hits, you move troops into the infirmary. The infirmary is my favorite part of Halls of Hegra, because it is the part I haven’t seen before. When a unit gets hit, you roll a die. The severity of the wound is determined by the roll. They enter the waiting area of the infirmary, at which point you can assign them to an empty bed—if you have one. Wounded troops in beds heal up every turn, getting progressively better. A medic can be used to accelerate the process. Troops in the waiting area get worse. By the end of the game, it’s a constant race to try and get beds cleared as quickly as possible.

Everything falls apart precipitously. As it should. How boring would it be if it didn’t? You end up with a pretty good army by the end of things, but you won’t be able to use them all. The troops you use need to be refreshed with supplies to be used again, and the bottleneck of low supplies gets worse as the game goes on. You watch in horror as your li’l cubes become worth less and less. Every few rounds, they drop precipitously in value. Awful. Just awful.

Sammendrag

Halls of Hegra is an excellent design, though it’s worth noting that it takes a while to get going on your first play. While the box says 75-90 minutes, and that holds out with repetition, the first game is long. This is not helped by the manual, which needs some work. I would be hard-pressed to improve on it myself, I can’t tell you what it’s missing, but it makes learning this straightforward game into more of an ordeal than it needs to be.

Otherwise, this is a worthy entry in the pantheon of solo games. I don’t love it the same way I love David Thompson’s solo games (Castle Itter, Pavlov’s House, Soldiers in Postmens’ Uniforms, and Lanzerath Ridge), which ooze story out of their pores, but I think that comes down to Thompson’s use of individuated troops. It’s hard to be overly invested in an individual hunter when it’s an anonymous wooden circle. That’s a matter of taste, though.

The marriage of worker placement to solo wargaming is executed flawlessly, and the game’s focus on the less glorious aspects of war is a welcome change. It’s not every day that you play a wargame that’s so focused on tending to the wounded and shoveling snow. If you’re an enthusiast for the genre, Halls of Hegra is well worth your time. If you’re a seasoned Euro gamer with interest in trying, the mechanics behind the design make it ideal for your first steps.

Add Comment