Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

The big question with any reimplementation, second edition, or reprint with rules changes is always the same—why?

There is the obvious answer—to make money. I find this to be a pretty lousy reason to do anything art-related, and it’s not my job nor do I have much interest in shilling for publishers. They have marketing teams for that.

Games appeal to me as an art form because they are not inert in the way that other forms can be. The interpretation of a book can change throughout time, it can undergo translation, it can get sequels, but the text itself does not change.

Games require us to bring them to life, and, when we bring them to life, unexpected things can happen, often things that are not intended. Players often discover strategies or behaviors within a game that upset or destroy the system the game is attempting to model for them or create dominant strategies that make features of the game untenable or uninteresting. Sometimes they find something divergent or unique that enhances the experience.

At the time I’m drafting this, according to BoardGameGeek stats, the original version of Great Western Trail has had 125,210 total plays, and the second edition has seen 17,739. That’s a lot of people playing a game. There are world championships (which are very entertaining to watch if you’re into this sort of thing), and the game still has a loyal following and is critically and popularly well-regarded.

Now, here comes Great Western Trail: Argentina, or GWTA, as I’ll refer to it going forward. What is interesting about this design, and what makes it exciting to me, is that it takes a system that has been put through numerous paces and attempts to make a more refined, purer version of the conversation that the game set out to do in the first place. It’s fun as hell too.

For the uninitiated:

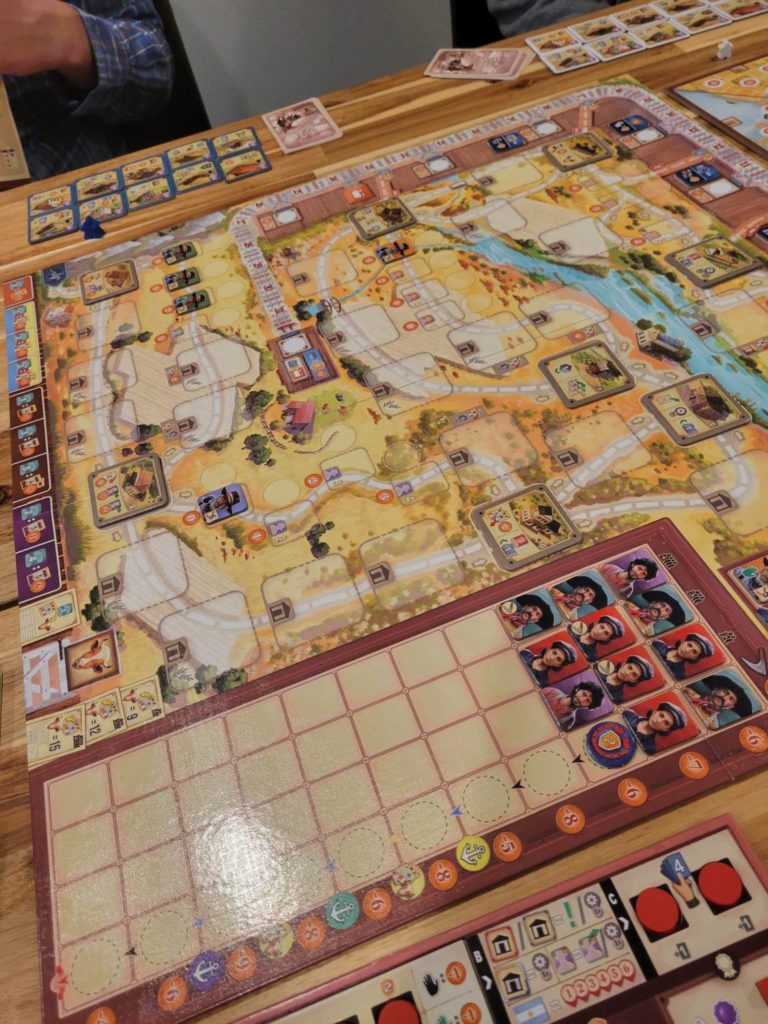

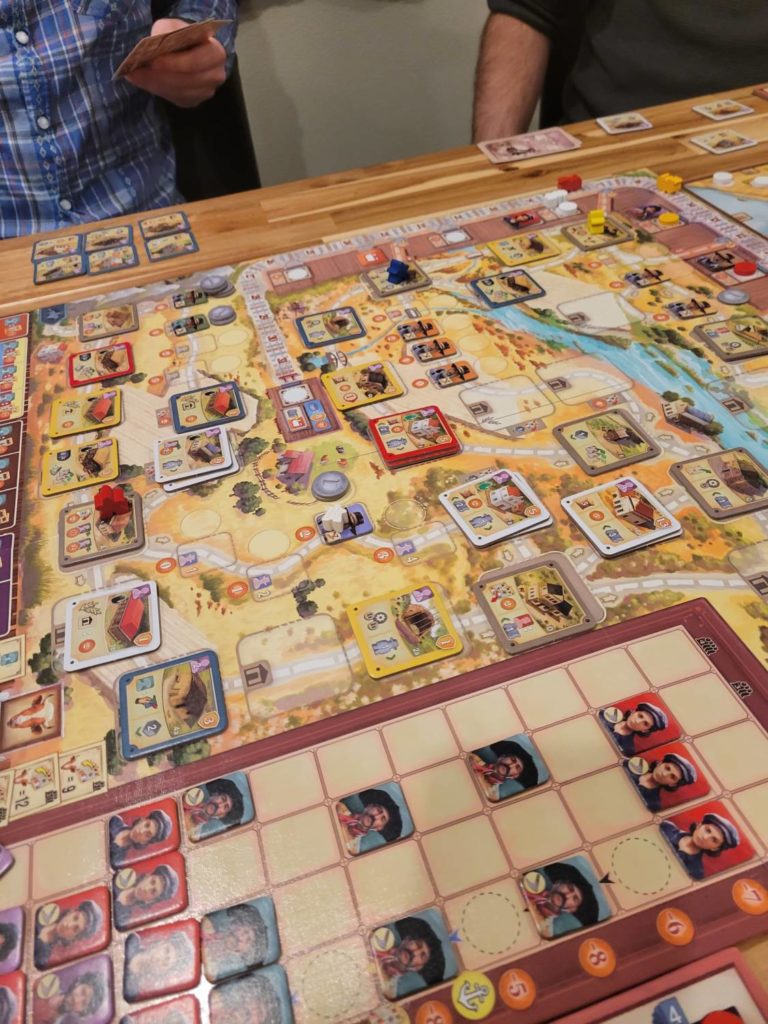

GWTA, like its forebear, is what I’d call an action queue game. You have a pawn that you move through a queue of actions, performing them at a pace limited by the amount of spaces you can move (which can be upgraded as you progress through the game). Action spaces in the game take the form of buildings or hazards (granjeros in this game). The masterstroke of the design is that your opponents are adding new buildings to their queues at the same time you are adding buildings to yours, and these buildings are obstacles to you both. The end of your queue is a delivery of cows to Buenos Aires, which is where the second critical mechanism comes in.

You have a deck of cards with cows of various values. When you reach the end of your queue, you “deliver” your hand to your discard pile, representing a successful delivery of cows to market. The catch is that only cows of differing values count toward the total money you make. So, if you deliver four grey ones (Niata) to Buenos Aires, you get 1 whole dollar. Cards are used as you move along taking actions to get benefits, allowing you to cycle through your deck, with the hope of having a good hand when you make your delivery.

The final main mechanism is a little train. There’s a track that you move a train along at the top of the board, and it gives you the opportunity to get benefits and boosts (in the form of station master tiles), as well as shortening the length of your queue. The farther you get your train, the earlier you can hop out of your queue and make a delivery (this is a departure from the original GWT).

There’s a fair degree of complexity to the game. There are also many subsystems. You need to manage four types of workers you acquire from a market, which upon acquiring, grant bonuses and help you build better buildings, move your train farther, get more cows, and acquire grain, one of the primary resources that you convert into additional points and benefits when you make a delivery. There is a variable end to the game, where players decide how quickly they can make the most points while rushing the endgame. There are spaces to unlock on a player board, and paths to choose to enhance the main actions of the game. There are small taxation costs you can throw in the way of other players to disrupt their queues (this is my favorite subsystem).

This is a review, not a rules document, so I’ll leave the rest of the mechanisms for you to discover yourself if this sounds interesting. Now, I’m going to return to my original question—why?

The beauty of the original GWT, and what is magnified in this reimplementation, is one of the most successful economic engines to be found in board gaming. This design contains a unique feeling that few low-conflict, high-computation games have: the feeling of battling a frontier.

Every game of GWT and GWTA starts the same way. You have this wide open shared board of neutral actions, a market of available workers to hire, and a hand of cards. Time to make your fortune. In GWT, the game is won and lost in how each player is able to see what kind of frontier is in play, and most efficiently create wealth for themselves while hamstringing the other players as much as possible.

Depending on who you ask about the original game, there are dominant paths, and paths that repeated plays have revealed as nonviable. GWTA is more difficult, more nuanced, and more opaque, and that feeling of having to fight an unforgiving frontier is still present, and is in fact more agonizing than you’d find in the original version of the game. You can make huge errors in judgment, and pay the price for them, and all of the dominant throughlines of the previous game are made more difficult and balanced.

There are many different ways this shows up in this reimplementation, but my favorite is the way that the boat mechanism works. In the original game, when you deliver, it’s sort of like one of those carnival competitions where you swing a giant hammer at a button, trying to get a little metal piece to rise up and hit a bell. When you say, deliver 10 dollars worth of cows, you get to place a disc on the 10 dollar slot, unlocking an area on your board, and getting some sort of advantage. You lose money based on counting these tiny railroad crossing signs. The farther ahead you’ve moved your train, the more profit you stand to gain, and the less the crossing signs deduct.

In GWTA, you make deliveries in much the same way, but you have to pay a new resource called grain, and if you don’t have enough, you lose money in a similar way to the original. However, instead of “cities” that you deliver to, you deliver to boats, which work in the same way, but at several critical junctures in the game, the boats “deliver” their discs to these extra city boards that offer additional opportunities to gain resources and bonuses. If your discs aren’t on the boat when they leave, you literally miss the boat.

What this offers is more nuance in the decisions you make, which is a great upgrade from the original, resulting in a more complex game with more depth, more choices, and more opportunities to screw it all up—for me, that’s what reimplementation is all about—making things deeper, more nuanced, more meaningful. You can’t ask for much better than that.

Add Comment