Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

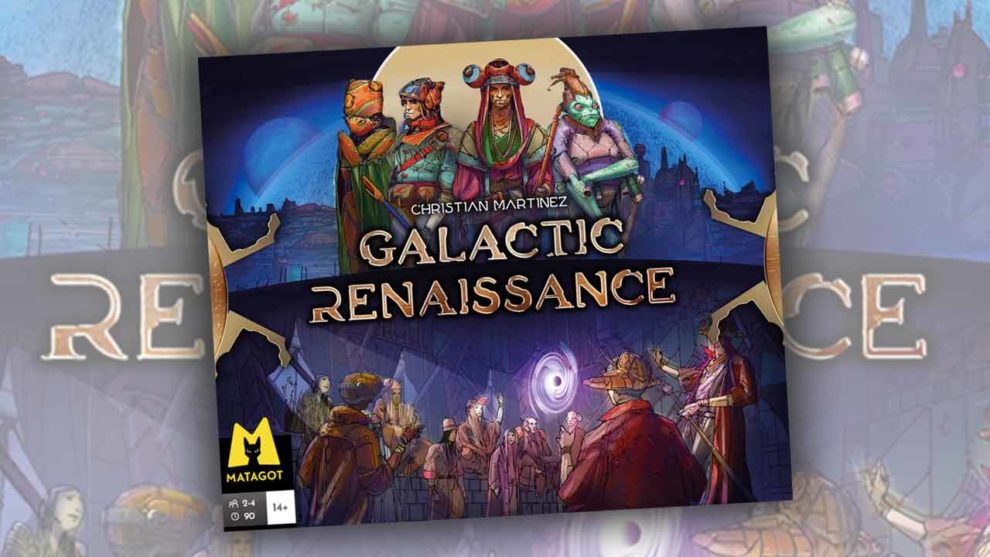

I’ve been on a roll lately, writing about new editions and implementations of games. Galactic Renaissance is very much in the same mold. While it is not a reimplementation of Inis (a titanic achievement in game design), it seems to be part of a “political trilogy” or expansion of the concepts laid down in that game.

Because of this little bit of information, I’m torn about which critical frame to adopt.

Evaluated as a design by itself, compared to the similar field of games about using patterns to score points, I’d say it’s a perfectly serviceable contract-fulfillment eurogame.

Evaluated against its sibling and predecessor, Galactic Renaissance very calculatedly accepts all of the wrong critiques and complaints about its precursor design, resulting in something that is essentially an intellectualized game of whack-a-mole.

I’ll start by evaluating Galactic Renaissance on its own merits.

The game is a deckbuilder of sorts, more in the Concordia or Faiyum slowly-add-cards-deck-management school than the Dominion buy-cards-from-a-big-market school.

Each player starts with a deck of the same cards, plus one additional “specialist” card, which is usually a variant of the starting “core team” with additional features. On their turn, players play cards from their hand, which have a range of abilities: from sending different types of pieces out to different planets in the play area, scoring points, gaining new cards, and maneuvering their position within the game state. Some cards allow you to immediately play another card, and you may discard specialist cards to draw additional cards as a free action of sorts, which can result in you cycling through your entire deck once you get into the later stages of the game. The system does eliminate the memory component of deckbuilding, enabling you to really refine the strategy you want to create.

Each planet in the game has special powers you can seize and use, and control and position on the various planets (often relative to other players) let you score points through shared objective cards that change as the game goes on and players score more and more points.

For example, one objective might say that you want to have exactly two pieces on a planet where other players have pieces, scoring you one point for each planet where this is the case. When you play the Senator card, you score all of the objectives you qualify for. The first player to hit or surpass 30 points instantly wins the game.

Conflict in the game is driven by a mechanism called stability, which is a set number of pieces that can be on a planet before the population of that planet gets, well, unstable. When this stability number is exceeded, disorder is triggered (i.e. combat). Starting with the active player, each player removes or repositions their pieces until a full round of said removing and repositioning occurs. After a round, if you’re back at or below the stability threshold, the disorder is ended. If that doesn’t happen, you go around again.

What this results in is a deckbuilder with a map, where you spend your turns in the game setting up configurations of pieces and then scoring them. There is a unique system of movement featuring three different colored portals, restricting movement between planets that share the same color(s) or portal, which throws a wrench in your plans.

At the end of the day, you’re bowling. Other players can interfere with your plans, but in most of my plays of the game, this usually happens by accident, or tangentially on the way to a goal. While there are significant ways to interfere with other players, conflict is usually very sedate and polite, as becomes a game that claims to be about peaceful galactic politics.

So, if you like the sound of this, back the Kickstarter. I haven’t seen the production copy of the game, so I cannot speak to that, but I could see a fun bling factor being brought into the game.

Now, here’s the part where I talk about Inis. Inis is a game about politics and the essential conflict that political struggle contains. Extreme violence is possible but usually doesn’t result in long-term gains. It’s a game about waiting for the right moment to seize power, about proving that you can lead. Everything in the game is designed to test your ability to evaluate a situation fairly, and not respond in anger to events that occur in the game. I frequently say that Inis enters the endgame when somebody loses their temper, and that person usually is the biggest loser.

A lot of people have criticisms of Inis that I think are pretty uninteresting. The first is that the conflict in the game is very punishing and often zero-sum or unpredictable in the outcome. The second is that the game goes overlong. I commonly dismiss both of these critiques, because very few games lean so hard into violence as a poor tool for solving problems. Violence in Inis, which on its face resembles a dudes-on-a-map beat-em-up, is bad. You don’t want to fight unless you can win, and that’s often very hard to do. Games often go overlong because people get too fixated on fighting, or are unwilling to sometimes pass their turn. Waiting is a virtue in Inis. And, buried within this, is a lesson about political struggle that players have to experience to understand.

What does this have to do with Galactic Renaissance? Well, it wraps up consistently in a tight 90 minutes because you’re just absolutely propelled toward an endgame through escalating scoring, and the conflict is much more rules-governed. In Inis, a fight can stop whenever players agree to stop. In Galactic Renaissance, you go a full round, check and see if the fight is automatically over, and then go another round if not. It takes agency and replaces it with maneuvering and rules. It removes decisions in favor of fairness and mechanisms.

I don’t like that. I don’t like seeing something mechanically and emotionally rich turned into a mechanistic operation that on its face seems designed to streamline the experience. It creates a second entry in a so-called “political trilogy” that has about as much politics and bite as a wet mop. So, decide for yourself. If you’re looking for a mechanically sound low-conflict area majority/contract fulfillment game, check this one out. If you want something in the vein of Inis, look elsewhere.

Add Comment