Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Let Freedom Ring

Monopoly tends to be a hot-button board game to discuss. Most people grew up with at least one copy floating around somewhere between their family and extended family, and it has remained ubiquitous since its release. There are hundreds of special versions and variations of the game. Famously, Monopoly originated as The Landlord’s Game, designed by American anti-monopolist Lizzie Magie. The game wasn’t intended to be a solid bit of game mechanics as much as it was intended to be a statement piece in support of an economic philosophy known as Georgism.

I am not a smart man. If you ask me how the economy works, most times, I would stare at you like a deer in the headlights, grunt, and shrug. But this bit of context is important because Freedom Rings is similar to Monopoly in so many ways. It wears its influence on its sleeve. It’s just that this game happens to be based on a different economic philosophy, taking influence from Stephen Taft’s 2015 book A True Free Market: Conversations on Gaining Liberty and Justice Through Economics. It’s unclear how involved Stephen was in the creation of the game itself, as there are no credits listed on the box or in the rulebook (other than the artist), but the opening foreword is signed by “Steve & Ben,” so I have to assume this is the same Steve(n) I talked to at PAX Unplugged about the game.

Though I am not an economics guy, playing this game made me more interested in checking out Taft’s book and getting a better picture of his ideas and philosophies because, unfortunately, I am not clear what the larger thematic points Freedom Rings is trying to make are from reading the rules and playing the game. It’s a lofty goal, to be sure, to try to boil down an economic philosophy into a digestible bit of board gaming, but when you aim for the moon, sometimes you don’t land in the stars. Sometimes, it’s just a long, long fall back to Earth.

Monopoly Mechanics

Out of the gate, the rulebook opens with a paragraph about the ideas behind the game and the design process. I am going to talk a lot about the rulebook. The rulebook is bad. It’s a brisk four pages that is roughly 90% dense text. The opening section explains that the goal of the game is to accomplish your chosen goal card’s win condition, then tangents into the game tactics you can use to accomplish these goals. The next section explains how to set up the game, listed under a section called “General Play”. Also under this section are the steps to a turn, the strategic advantages of accumulating property in the game, how interest works, what happens when you land on a property someone else owns, and the various different things that can happen when you land on a given space.

There’s an aside about how one of the industries differs from the others. It’s a bit all over the place and repeats itself frequently. There’s a QR code to scan if you’re tired of reading and want to watch a learn to play, but as of my last play of the game, it goes to a website without a video but instead containing more text. I am grateful that I did scan this code after my first playthrough because the rules listed on the website are even shorter than the ones in the rulebook but contain crucial pieces of information not present in the rulebook! For example, we did not understand how the endgame worked in our first playthrough. There’s no section in the rulebook for endgame; it simply says, “The game ends when a player declares, at the beginning of their turn, that their goal has been met and shows all other players their chosen goals”.

In our first game, I reached my win condition threshold, and we thought… okay! Game over! That feels weird! The website, however, says that final scoring is calculated with the value for each property square minus the debt the player has. This was not clarified in the rulebook. The rulebook does not mention the parks on the board or what they do. The website simply says they cannot be claimed like other properties.

All of this to say, I think I now have a handle on the general progression of the game.

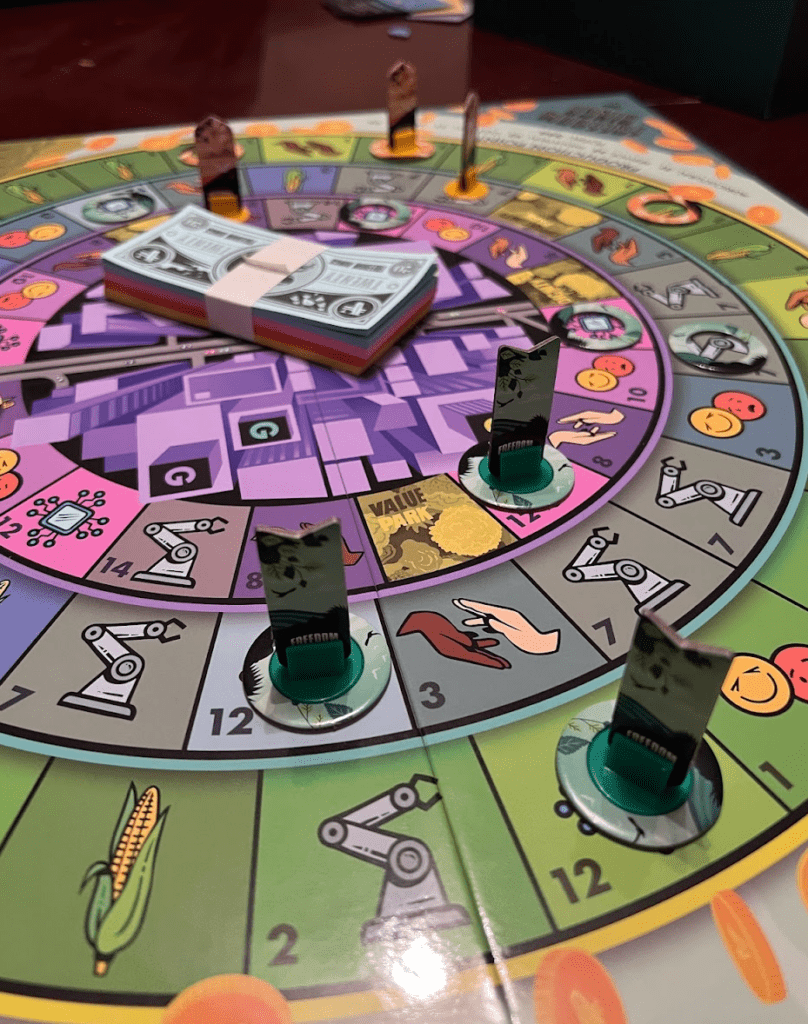

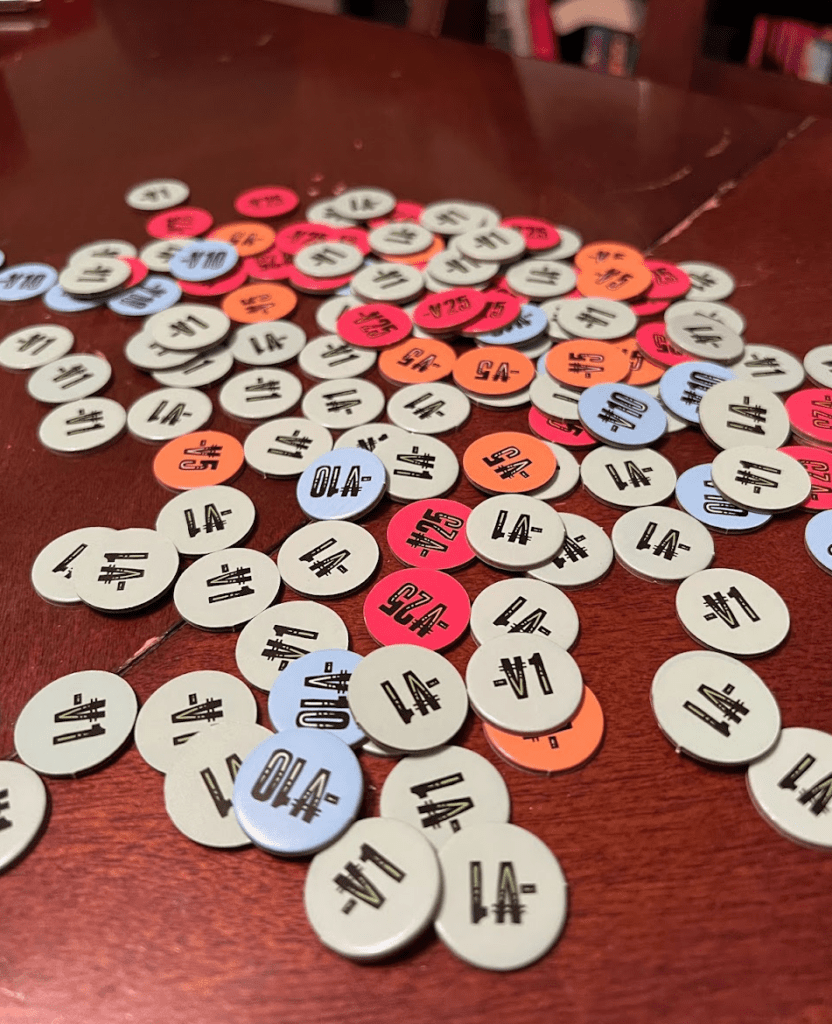

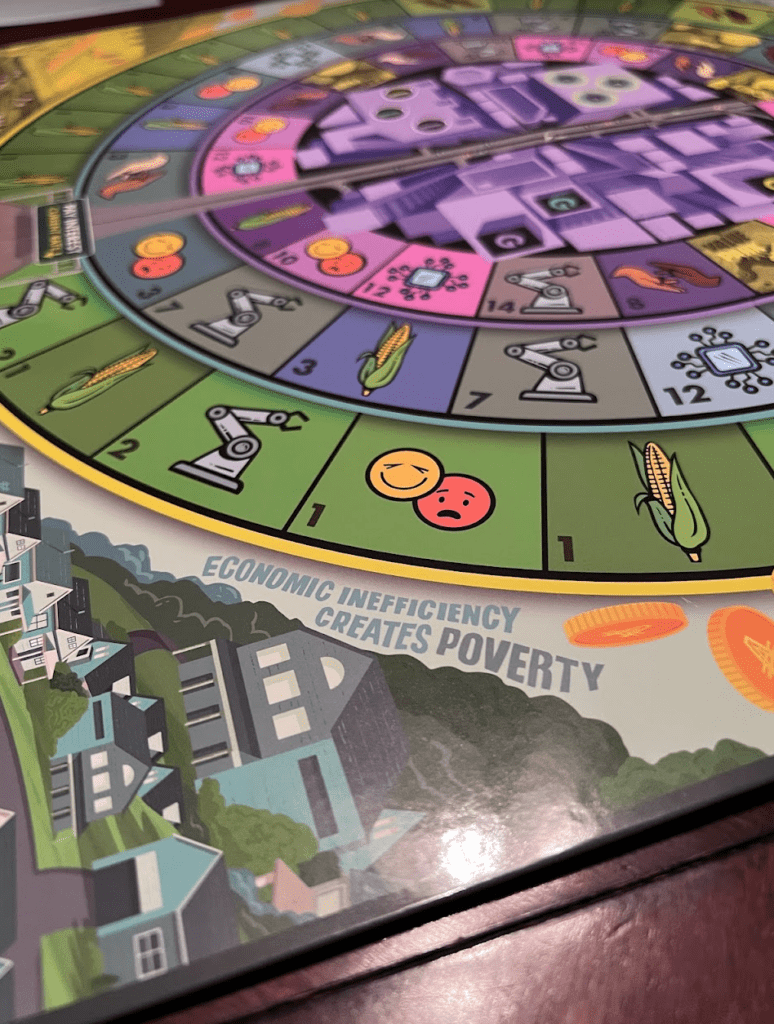

At the start of the game, players choose one of seven goal cards from their hand to be their win condition for the game. There are five goal cards specific to the five industries in the game (Agriculture, Industry, Service, Culture, Virtual), plus one card for the most wealth and one card for diversifying across industries. On your first turn, you will claim any agricultural space on the outer ring of the game board. This is your starting space. You will choose one of the three rings on the game board (rural, suburban, and urban) to activate on normal turns. Then roll a die. Move your pawn on that ring that many spaces. If it’s unclaimed, you can claim it by paying for its printed production value. If you don’t have money, it’s okay, you can go into debt to pay for it. If it’s claimed, you must pay rent to the owner equal to its production value. Regardless, you can also claim any unclaimed space on the ring you’re on and then move your pawn to that newly claimed space. So… rolling the dice only really matters if you’re going to have to pay rent to someone. When you cross the Pay Interest Street (this game’s version of passing “Go” in Monopoly), you must pay interest equal to one dollar for every ten dollars of debt you have. (As a note, the game doesn’t refer to anything by an actual currency name; it calls debt and money “units” instead.) You can then barter and negotiate to trade resources or properties with others at the table. After you’re done, pass the die to the next player.

Instead of taking a normal turn, you can take two alternate turns. First, you can also consolidate your properties. This lets you trade in two matching properties on the outer ring for a single matching property on the next ring up. This matters because most industries get more valuable as you get closer to the inner circle. However, the “Virtual” industry always costs a lot in every ring but has the bonus of giving you +4 to your virtual spaces once you have three of them. Second, you can become a “Power Player” if you own enough properties on a given ring, letting you take actions that affect the whole game, such as modifying the interest rate or productivity values on a given ring or changing your goal card out for a different one.

What’s the Point?

Once someone has met their goal, they announce it at the start of their turn, and that’s the ballgame. I think. That’s what I deduced from the video-less website with different rules. It’s just a race to complete your goal first, all of which are hitting certain score thresholds by adding your goal-related properties and subtracting your debts. You get there by rolling dice that only matter if you land on an owned property because you can just… buy any space you want on that ring, anyway. Sometimes, you’ll get extra debt units or something if you have enough existing debt. The difference between debt and money barely matters because everything can be paid for with everything. It settles into a rote experience pretty fast. Once properties are snatched up, the only intrigue comes from possibly negotiating with other players. If you see someone scooping up all the cultural properties, you might wanna cut them off and force them to negotiate with you, for example. It runs into the problem many negotiation games have, where your ability to complete your win condition is wholly reliant upon other people allowing you to do so.

And that’s even more frustrating because this isn’t really a game about negotiation! It’s sort of an afterthought. In most games of Freedom Rings, there wasn’t much negotiating. This is partially because the game’s mechanics allow you to buy any spot you want every turn. I can’t believe I’m about to go on record defending Monopoly (and I’ll never admit to it if you tell anyone), but at least with Monopoly, when played correctly, properties that you land on MUST be bought, or they go up for auction immediately. This can lead to some jockeying for position and force some interesting moments of negotiation. (I said it can do that, not that it does regularly). But here, you can just go buy another space. There’s no reason not to just go all in on your goal because there’s nothing getting in your way unless another player chooses the same goal randomly or wants to tank their own goal to spite you.

Maybe this is for you! Maybe your family loves Monopoly, and you’re looking for a progressive, less capitalism-worshiping take on that specific experience. You’ll find plenty to love that’s familiar here, even down to the flimsy paper money. To its credit, the game has outstanding artwork and graphic design. The game board is colorful and pops visually. Artist Dave Homer did a great job creating a clean, sleek visual language for the game.

Look: there’s probably a deeper game here beneath the surface than I saw in my handful of plays. I actually like the “Power Player” mechanism, where you can spend a turn to make a major, permanent change to the game state. If I were to theory craft what a deeper game of Freedom Rings might look like, it would involve balancing the game on a knife’s edge around these powerful turns where you can upend someone’s whole strategy and force them to the negotiating table. That is interesting. That is cool. That is not what happened in any of the games I played. Freedom Rings needed a bit more time in the oven to produce anything resembling an experience I’m ready to try again. The art is pretty, and I’m actually fascinated by the economic theory that inspired the game. But if you’re going to borrow mechanics and take inspiration from a game about the economy, why did it have to be Monopoly? Food Chain Magnate is an excellent distillation of supply and demand. John Company takes a deep look at the principal-agent problem. Even if searching for something simpler, Acquire is sitting right there. There are tons of better starting places for designing a game about specific economic theories. It’s a shame such a unique theory wound up stapled to such dated mechanisms.

Wow. A game that has to be compared to Monopoly, and loses. I might need a shower after reading this one. 😀