It’s been a bad year. I have never been proud of being an American, and 2020 has only served to validate my disgust with my country and its treatment of the disenfranchised and powerless. Given these circumstances, it’s the perfect time to play Rick Heli’s Founding Fathers, a game about attempting to wrangle political chaos for personal gain.

My father is always describing me as being farther to the left than anyone he’s ever met and he’s telling the truth. If you’ve read any of my writing, you’ve likely caught a whiff of this. I’m going to talk about games, of course, don’t worry! But I’m also going to talk about the personal, which is impossible to divorce from the political. Negotiation games are the most personal games that I know and therefore cannot be separated from the political. It doesn’t hurt then that the game (or argument simulator) that I will frame this piece around is one about the founding bros of the good ol’ US of A.

We’ll come back to my politics.

The Game of Wigs

2007’s Founding Fathers (not to be confused with 2010’s Founding Fathers, a game co-designed by Jason Matthews, one of the designers of Twilight Struggle) is a negotiation game modeled after The Republic of Rome, a game that I have never played and will not speak more about here.

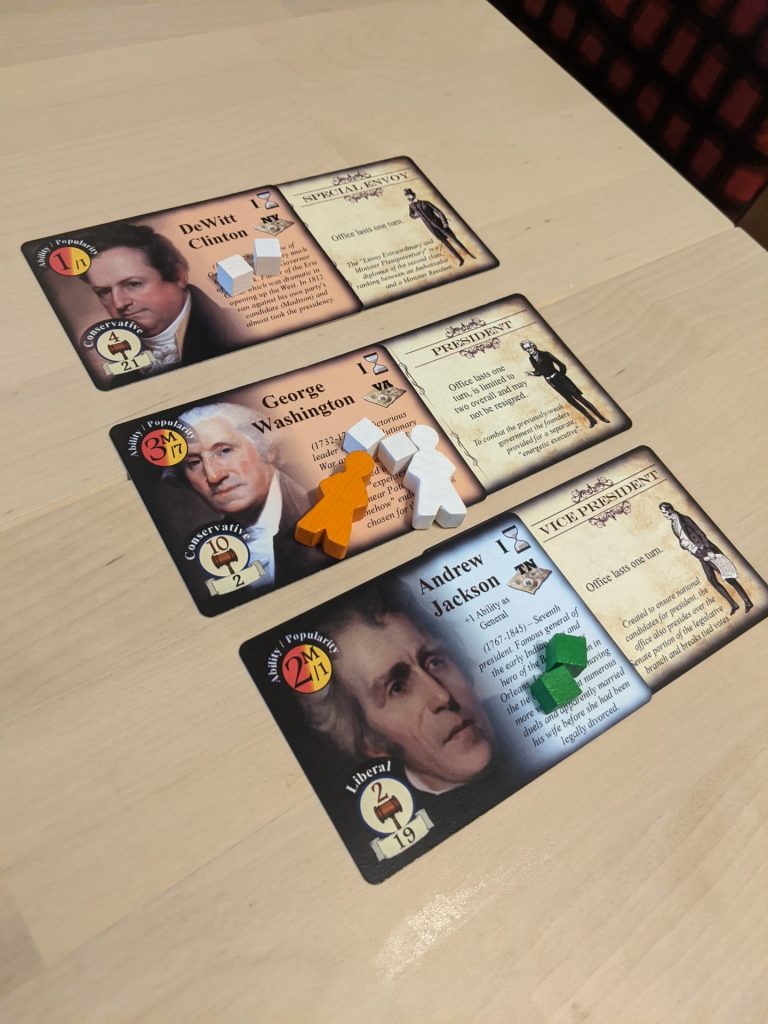

Each player is a “faction” and has a roster of cards representing various politicians of the period. Each politician has stats that indicate their ability, age, popularity, political party (liberal or conservative), votes in Congress, and possibly a special ability of some kind. The faction votes as one, regardless of party (with a few exceptions), and the faction gets to manage a faction supply of resources called influence cubes. Individual politicians can have their own private stashes of influence cubes as well.

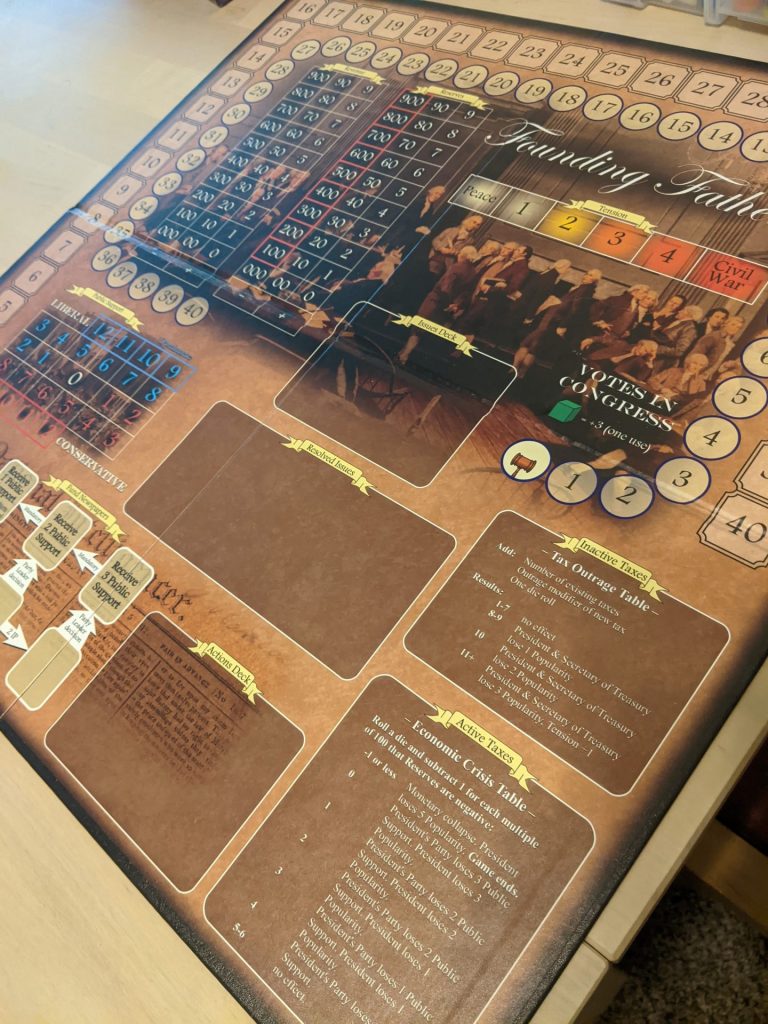

One player (whoever starts with Washington in their roster in the general scenario) is the president and another player is the vice president. The general flow of the game is this: there is a deck of 67 “issue” cards, which the president flips one at a time, resolving each one before flipping the next until they’ve resolved four of these cards and assigned all of the game’s offices to different statesmen, at which point a new election is held. These cards represent challenges to the budding republic and have requirements. Usually, the president will need to appoint an officeholder like the Secretary of State to resolve an issue using their ability stat (which can be supplemented by the green influence cubes), which will have effects on the republic. The republic is represented by a board with different statistics measuring fiscal health, the movement toward civil war, and party dominance. Depending on how issues resolve, the president and officers who work to resolve an issue will receive white popularity cubes, which are points when the officer retires/dies or the game ends.

Offices are powerful because they give officeholders a popularity cube upon receiving them and they give players agency in resolving other issues. There are also issues that require all players to use their congressional votes to pass/fail issues, which also affects the president and relevant officeholders. In addition to the issues deck, the president can try and pass tariffs and taxes to raise the country’s revenue. Players have a hand of action cards, which include more statesmen that can be added to a faction’s roster or traded with other players, and action cards that allow players to create chaos (in our last game, one of my friends killed one of my politicians in a duel).

The game ends when the players have collectively resolved all the issues through 3 decks of play, financial collapse occurs, or the country descends into civil war.

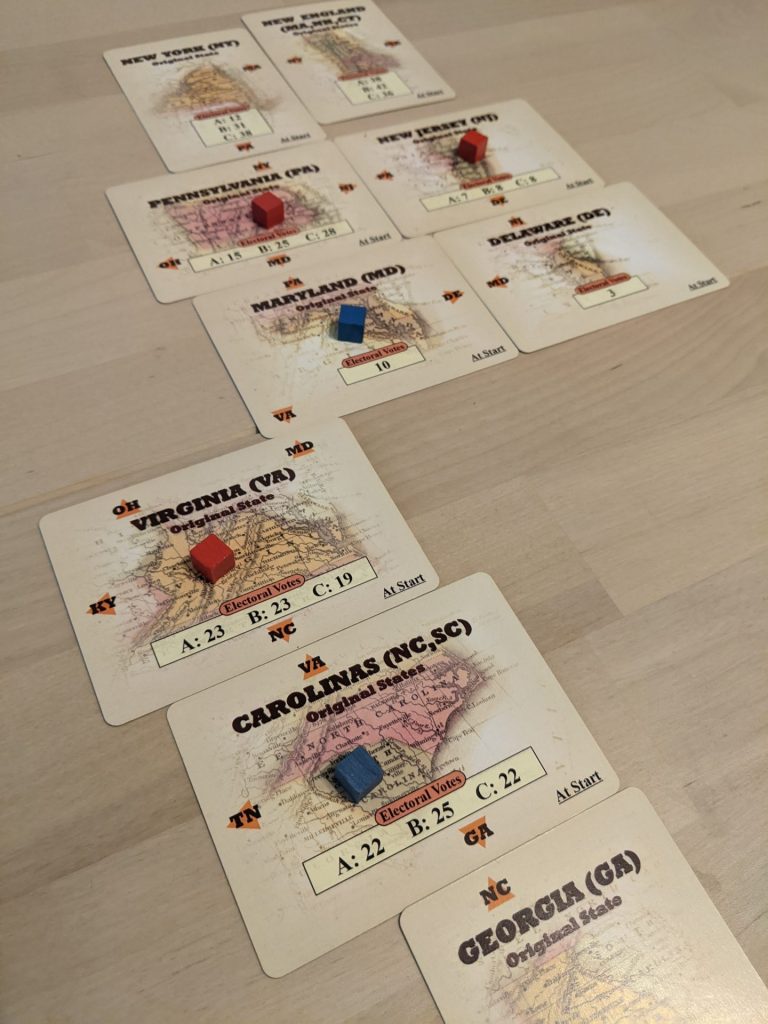

If it sounds a little nuts, it is. It’s complex, and there are four different ways elections occur after the president has assigned all the offices and resolved four issue cards. Players grow the union with more and more states, which, come election time, form a sort of area control contest as two tickets (or possibly four tickets) compete to become president and vice president. You gotta be president. President gets to be in the hot seat and scores beaucoup de points.

Negotiation: The Board Game Equivalent of the Wilhelm Scream

I forget who said it, but somebody said, “All games are negotiation games.” That’s crap. If you abstract a statement to the point of utter meaninglessness, then yes, all games are forms of negotiation. True negotiation games are games that are formed and framed by a set of rules, but the tenor, pace, and tone of the game are entirely defined by the will and mood of the players involved. Mood, will to power, the desire to dominate that day, the desire to befriend that day — that creates the game you have when you play a true negotiation game.

In this sense, there is no better experience for my money than Founding Fathers. To quote one of my friends who played: “I remember feeling the complete range of human emotions, from abject elation to foppish indolence.” Founding Fathers generates a complete sense of catharsis; also known as me threatening to rain hellfire down on someone if they didn’t vote yea, and my nearly being reduced to tears by the ire and stonewalling of my opponents when I pulled ahead and started trying to ruthlessly generate points. It also took 8 hours.

Now, What Does This Have to Do With Politics?

I enjoy games about the manipulation of capital and power because, for most of my life, I have been harmed by those forces. My family was bankrupted again and again by medical expenses and debt; I’ve seen firsthand the horror generated in the lives of people I love by cruel little men who preached austerity but practiced cruelty. My life, evidenced by this supposed “worst” year and most years before it, has been characterized by a lack of control, a lack of power beyond mostly meaningless consumer decisions. Getting to play power fantasies about affecting this stuff does not affect that reality, but the fantasy and politics of such games sometimes help me get through the day.

Let me tell you about a story in the game.

Very early on, the issue card “End Slavery” appeared. This card in isolation does not seem to do much. It grants a modest gain to the power of the liberal party and it slams the country’s financial reserves by -200, which can possibly result in the game ending early if a die roll lands wrong and we don’t pass some taxes. We survived it, though a few players were worried about financial collapse, and we ended slavery (which also had a high difficulty level, so we had to pool influence cubes to do it). Having never played through the game before, we did not realize [SLIGHT SPOILERS AHEAD] that ending slavery early results in around 12-14 issue cards never entering the game, as those issues (and the expansion opportunities they offer) are dependent on slavery’s continued existence.

We also did not perform the “Indian Removal Act”, though we were slap-happy around hour 6 and probably didn’t think about the ramifications of that one, which also prevented us from adding a bunch of states to the union. We blitzed through the remaining issues of the game, fought a few wars, and the game ended with a friend gathering enough points after a single party dominated election (a scenario that can occur within the game).

It wasn’t until the next day that I realized something about the game. By refusing to continue slavery and displace indigenous people, we inadvertently messed up the empire-building and expansionist project of the early union, resulting in a country that didn’t have a mess of states, and was unable to become the shambling monstrosity it is today. We had power for a day and painted a fantasy picture of a different America. Was it a game we played? I don’t know. Did we have fun? At times. At other times, the entire spectrum of negative emotion unspooled itself in the medium of cardboard and plastic. But the experiences were undeniably meaningful and valuable.

And if that isn’t the intersection of the personal and political, I don’t know what is.

Note: I do not normally give out information about where to purchase a game, but this one deserves some exceptions. It is published by Up & Away Games, a publisher that prints entirely through The Game Crafter. You can acquire a copy for yourself at this link. I also recommend getting the first two small expansions, as they allow you to counterfactually bring female politicians into play, as well as giving more negotiation options to players (AKA “more yelling”).

Add Comment