I have the great fortune of serving as a member of the tabletop media. As a result, about 95% of the games I cover are review copies forwarded by publishers. That helps keep personal spend at a minimum, which is vital for a person who reviews about 125 games a year.

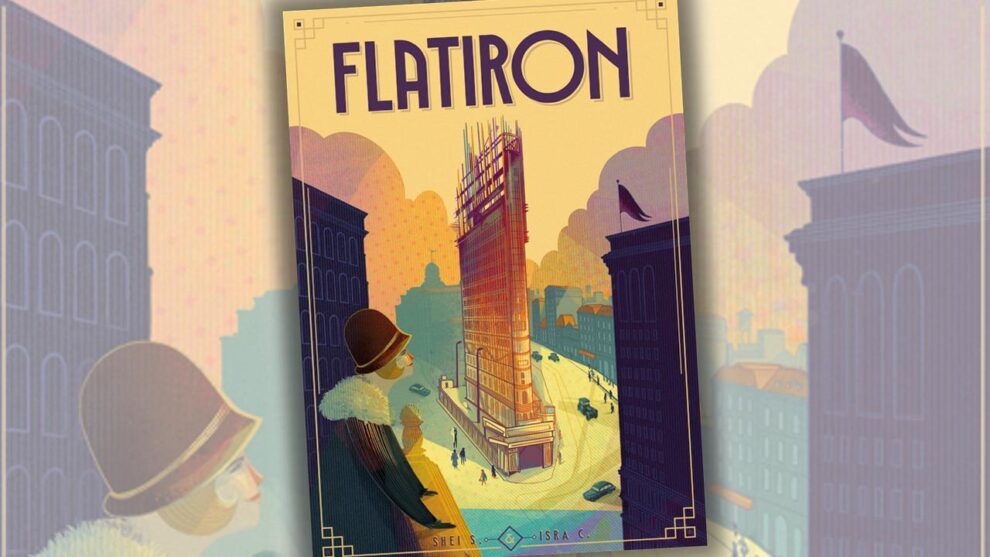

However, I occasionally break my own rules when a game tickles my fancy. Llama Dice, the design duo composed of Israel Cendrero and Sheila Santos, is the main reason for me to break some of my own rules because they are the duo that gave us The Red Cathedral and The White Castle, two of my favorite games of the last five years.

When I learned that Llama Dice had a game hitting at SPIEL this year, I happily stood in line to pay 25 euros to grab a copy. That game is Flatiron (2024, Ludonova), a 1-2 player city-building game based on the duo’s personal travel to New York City touring some of the great architectural wonders there. The duo’s appreciation for these trips is detailed in the acknowledgements of Flatiron’s rulebook.

Soon after I returned to the US, I got Flatiron to the table for three plays: two solo, and one with my wife. Flatiron is far from the duo’s best work, but as a quick-playing efficiency model with a handsome “toy factor”, Flatiron is worth a look.

Pillars, Pilar

The game is set in the early 1900s, as competing architects race to build the historic Fuller Building (later renamed the Flatiron Building) by acquiring then placing building materials and adding floors to a cute 3-D structure on a small map of the intersection where the real Flatiron building is today. Using a single pawn action selection system, players have to move their architect to a new location each turn to take one of three actions:

- Buy a card,

- Take actions,

- Take two dollars.

Whereas some games make the “take a buck” action feel like a pass action, I found myself taking the $2 option in Flatiron a few times each game. That’s because money can really tighten up if a player can’t optimize their player board, which serves as the heart of the game and offers its most interesting decision points.

Each player’s personal board—unique from their opponent, with eight different player board choices in the box—serves as their action menu. The four spaces on each player board are the same four spaces on the Manhattan map: 5th Avenue, Broadway, 22nd Street, and 23rd Street. When a player wants to take actions, they move their architect meeple to one of those locations and trigger every action in that player board column from top to bottom.

When play begins, the complete list of actions available to each player at a location is always two—a mix of buying or selling building materials (represented simply as pillars that make up each floor of the skyscraper), taking a little cash, adding pillars to a floor, or completing a floor by dropping a new tile on top of the previous floor’s three pillars. Buying new cards allows a player to slot a new card in one of the four action spaces, either above or below existing actions (with a limit of three cards per action space).

This gives Flatiron some really nice heft. I loved figuring out where to place my cards so that I could trigger future actions in a way that fit my strategy. Card purchase and placement also comes with an additional consideration. Each card comes in two halves, and each half comes with a reputation score. When you initially tuck a card, you have to commit to either the top action or the bottom action of that card.

At the end of the game, columns that have a net positive reputation add five points to your score, with negative rep costing a player three points per column.

So, you want to add cards that keep the reputation balance close to zero, ideally positive. However, as you would imagine, the cards with a negative rep do some really juicy things by making some actions much cheaper than normal, providing a large boost of coins, etc. How can I simply build a good engine when there are options for a truly great engine lying around right in front of me??

Flatiron also features a fifth action location, City Hall. At City Hall, players can buy end-game scoring cards instead of cards that strengthen the engine. Only one action is available at City Hall: whatever is pictured on the current Newspaper token. This is usually a slightly better action than the ones on a player’s personal board, and they change with good frequency throughout play when other players earn Newspaper tokens (used as bonus actions) when players trigger scoring milestones for every 10 points on the score track.

Games run in a straight line. There are no end-game income actions or traditional rounds in Flatiron. Players take turns until someone builds the fifth and final level of the building—the roof tile. Play immediately ends, then scores are totaled, mixing points scored during the game with those end-game scoring cards and adding or subtracting points based on reputation. In the case of a tie, the player who built the roof wins.

I Liked It More Than My Wife Did

Flatiron was an interesting time at the table. The card tuck mechanic—building a new series of actions each game that help make visiting certain street locations pay off in a unique way—is the reason to play Flatiron. You’ve probably seen tableau building mechanics quite often if you have tabled other fun engine builders like San Juan, Terraforming Mars, or Race for the Galaxy, so you know how much fun it is to take actions late in a game where your initial plans have led to taking a small river of actions to maximize a single turn.

Flatiron certainly has those moments. That is balanced against a feeling that you are almost always setting up your opponent, a feeling that both my wife and I agreed on during our two-player game. I don’t think that’s an issue with the design, but rather a personal feeling that competing with someone should feel more like I am not making decisions based solely on how much this helps my neighbor! “I really don’t want to finish that floor,” my wife said at one point. “I know on the next turn I can’t block you from finishing the floor and scoring six more points!”

And that happened a lot. One player will finish a floor, which sets up the other player to do a double-build of pillars on the next floor, scoring them nine or ten points, triggering another bonus for that player as they advance on the score track. (The person who gets to the next 10-point milestone first draws two bonus tiles, selects the one they want, then hands the other to their opponent. Everyone gets something, but the person in the lead gets the thing they want most!) If one person places the third and final pillar on a floor, it felt like the other player was always ready to place the floor tile and score six points.

As a tug-of-war, I was OK with that. It also led to each player having a couple of very sweet combos in that two-player game. This also happened when I played against Daniel Burnham—the real-life architect of the Fuller Building who is also your opponent during solo play. The combos were everywhere. In a lot of ways, Flatiron is like a car drifting game—it’s a blast to piggyback off of someone else’s great driving (or in the case of this game, great building!) to score points and move into the lead. Lurking just behind another player and setting yourself for a big turn soon after your opponent does a major action quickly became a hallmark of that two-player game.

I don’t think of Flatiron as timeless, though. In terms of replayability, you do get a nice mix of player boards, but the actions are mostly the same and just positioned in different street locations. I highly recommend using the “hard” side of each player board right away, to increase the variability in the ways each opponent attacks the game. The cards have a nice mix of actions, but there are limited end-game scoring cards and some just felt categorically better than others. In a game where there are certain colors of pillars on each floor, those might score a ton of points for the player that snatches those from City Hall first.

After my three review plays, I’m struggling to imagine a scenario where I would consistently reach for Flatiron to break it out with my wife over other games. Flatiron is a game that you will want to play with the same partner regularly—the iconography is a bit difficult, and the game’s rhythms would work best with equally-matched opponents—and we prefer the other Llama Dice designs mentioned earlier. The White Castle, like Flatiron, plays in about 45 minutes with two players, and I’m still trying to figure out ways to master The White Castle with a decision space that is ultimately more interesting.

Flatiron was fun. It’s not a lifer, but I needed to know if Llama Dice brought it home again or not. I’ll have to settle for a good-looking production that provides a decent amount of fun on a Friday night.