Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

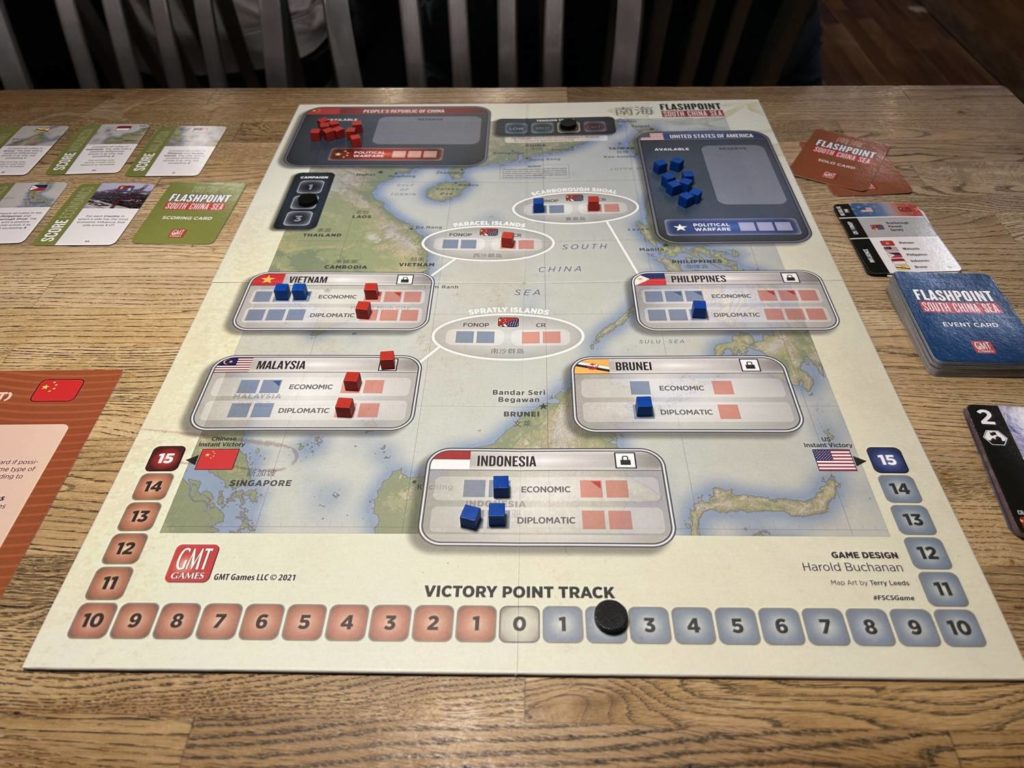

Flashpoint: South China Sea, a two-player game from designer Harold Buchanan and publisher GMT Games, is themed around the political tensions between China and the United States of America in the South China Sea. Fundamentally, it is a straightforward area control game, with players taking turns to manipulate economic, diplomatic, and military influence in Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines. Think of it as tug-of-war on an international scale.

Players take turns playing a card from their hands for one of its four different effects. This is standard stuff for Card Driven Games (CDGs), a family of designs especially popular in wargaming circles. Flashpoint is an especially approachable entry in the CDG canon, so let’s take a moment to get up to speed those who aren’t familiar with CDGs.

Card Driven Games

CDGs are designed around multi-use cards that depict individuals and events related to the game’s setting. The most famous example is almost certainly Cold War favorite Twilight Struggle, which includes cards such as “Fidel” and “CIA Created.” At the beginning of each of the three brisk campaigns that comprise a game of South China Sea, both players receive a hand of six cards. They can be used for the following qualities:

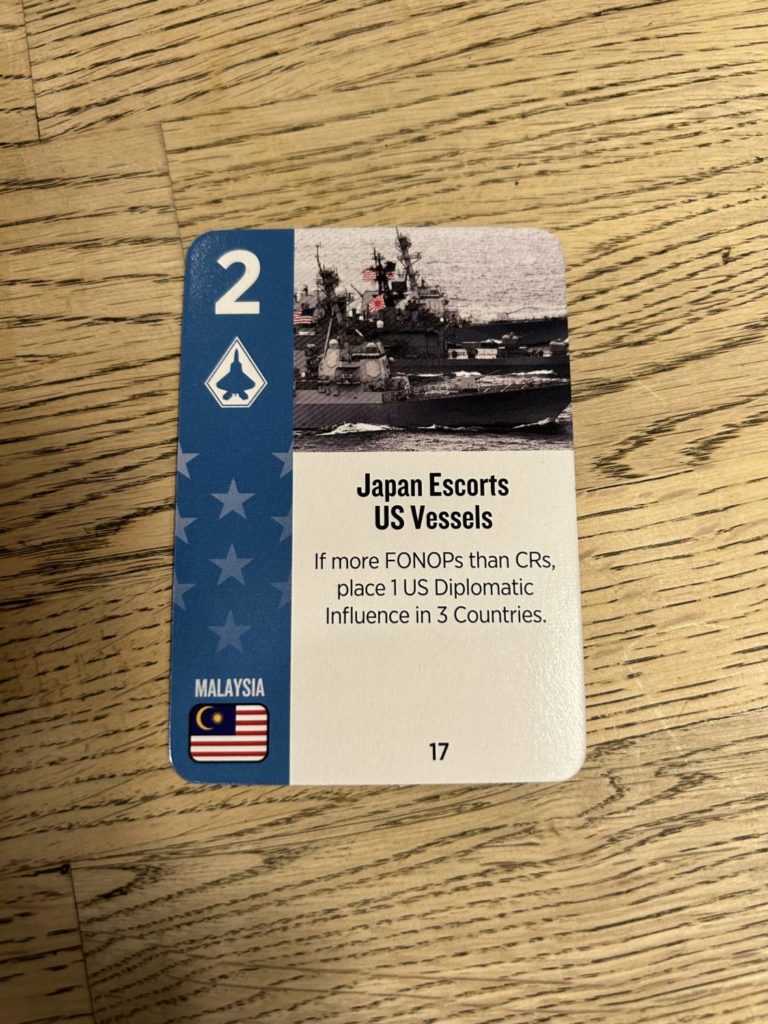

1. Event

This will in some way change the circumstances on the board. “COVID-19 Outbreak in China,” for example, allows the U.S. Player to remove up to three Chinese economic influence from the board, while removing just a titch of their own. A player can only use a card for its event if the event matches their side. “COVID-19” is a blue event card, and can therefore only be played by the U.S. This has troubling real-world implications if dwelt on for too long.

2. Operations Points

Each card includes a number between one and three in the upper left corner, indicating the number of Operations Points (OP) that card is worth. OP allow you to place various types of influence, to deploy FONOPs and CRs, or to wage Political Warfare (don’t worry about it). The stronger the event, the higher the OP value of the card.

3. Mode

Mode is how South China Sea deals with the luck of the draw. If your opponent discards an event of your own that you’d like to use, you can discard any card with a matching Mode—the icon under the OP number—to use the previously discarded card for either its event or its scoring criteria.

4. Scoring

Each card includes an icon in the lower left corner that corresponds to one of the seven scoring criteria. If you find yourself in an advantageous position somewhere on the board, you can discard a card to score those points immediately. The scoring card is flipped over, preventing it from being scored again that round.

Nothing Is as It Themes

I can understand why CDG designs have been popular in war and historical gaming for much of the last decade. They provide a thick varnish of theme, connecting the mechanics of what is essentially an abstract exercise to its real world inspiration. When I first opened my copy of Red Flag Over Paris, a magnificent CDG, I spent two hours reading through the deck and the historical notes, marveling at how the effect of each card was intertwined with what it depicted.

In the case of Red Flags, that attention to historical detail comes across in the gameplay. You feel the stakes of your decisions. Twilight Struggle overwhelms me with its decision space, but there is a thematic sense of the unknowable, a vastness to the scale that feels appropriate to two global superpowers duking it out. The biggest issue I have with South China Sea is that the theme doesn’t come across in gameplay at all.

Part of the problem may be that there is no true narrative end to this game. Red Flag ends with either the taking of Paris by the French national government or the Commune succeeding in their takeover. There’s a premise, a middle, and an ending. Twilight Struggle ends with one side or the other emerging from the Cold War victorious, and you see the cards change as the in-game years pass. South China Sea uses one relatively small deck and ends, well, after three rounds. It ends at an arbitrary point. The story isn’t over. The battle for influence carries on after the game ends.

That strikes me as intentional. It makes sense that designer Harold Buchanan purposefully left the door on the endgame open. While most CDGs use cards based entirely on real historical events, and cover “finished”—in so much as anything in history is ever actually finished—happenings, South China Sea depicts an ongoing situation and uses some cards based on potential future events. It’s a fascinating idea, even if I think the arc of the game suffers as a result.

Clear and Present Danger

I’ve written about my mild discomfort with war games before. The thrust of it is that I struggle with abstraction of human deaths and suffering in an explicitly non-fictional setting. The war games I enjoy make you feel the ramifications of your decisions. At the same time, I am predisposed towards games that center around political tension. Does this hold up to scrutiny? It does not. Enjoying political games while having slight reservations about war games reminds me of what may be my favorite tweet of all time: “I’m a social liberal, but a fiscal conservative. The problems are bad, but the causes? The causes are good.”

The theme of Flashpoint: South China Sea is appealing to me. I especially love the idea of a CDG depicting current events. That promises a rich space for sincere investigation of how these sorts of situations have to be navigated. As designed, South China Sea falls far short of those possibilities.

Your decisions can only have so many repercussions. War, in this game, is impossible. I have philosophical issues with that, but in the immediate the gameplay suffers for the lack of stakes. There are so many turns where I or my opponent said, “Sure, I’ll do this, this seems like something to do,” because nothing feels consequential. If tensions get too high, everyone stops deploying warships. That’s not how it works in real life. Buchanan has designed a game with unflagging belief in Pax Americana. International relations with the bumpers on. The realities of tensions in the South China Sea are not a game. I wish this game understood that.

This was actually the first GMT game I ever played. I found it interesting, especially the part where players bid victory points to get to select China, who starts the game with a more firm footing.

In my game, I figured out how to get China to over-extend and ended up with then not being able to really do anything their last 2 turns. It is an interesting push pull game, although I am not certain how much replayability their will be once you have seen everything the game has to offer. Then again, playing any game 10 or so times, and this one is short enough to do so, is still pretty good.

It is a rock-solid system, and I am looking forward to what comes next in the series. I would find a lot more replayability in it if I felt the narrative, I think, but I also agree with you that any game I buy that gets to the table at least ten times was well-worth the money. Thank you for reading!

I have enjoyed this game, with the understanding that the design supports a game of conflict rather than a traditional war-game with specific counters and unit stats. I did find it thematic, at least in so far as the cards do represent recent historical events and other incidents that have influenced the growing tension in and around the SCS, and China’s growing global ambitions in the face of what it calls American hegemony.

For the ease of set-up, “ripped-from-headlines” feel and gameplay time, this is an entertaining diversion while I wait for heavier titles to land at my doorstep, after they have been delayed by the “COVID-19 Outbreak in China”.

I am satisfied FSCS does not see to emulate the likely consequences of open conflict with a near-peer adversary.

In that scenario, we all lose.

I’m glad to hear you’ve enjoyed it, and thank you very much for reading! I love that FSCS doesn’t have complicated rules for the sake of having them, and I am certainly not someone who needs loads of stats and details to feel a theme. I’m the guy in the corner of the insane asylum insisting that Lost Cities is deeply thematic as a play experience. FSCS is absolutely thematic in terms of everything fitting and making sense. When I criticize it for lack of thematics, I am focused on the emotional experience of playing the game, rather than the details of gameplay itself.

I completely agree with you about the last part. I don’t need the game to emulate such a scenario all the way through, but the lack of concern that there could be severe consequences didn’t sit well with me as I continued to play.