Upon hearing of the Orient Express, I’d imagine a great majority drift—one way or another—to Dame Agatha Christie’s classic mystery. Some may think of Albert Finney’s classic Poirot, or David Suchet’s mainstay portrayal, or maybe Kenneth Branagh’s more recent iteration. Personally, I think of picking up the book again (and again, because why not?!). Regardless, there’s a priceless mustache involved.

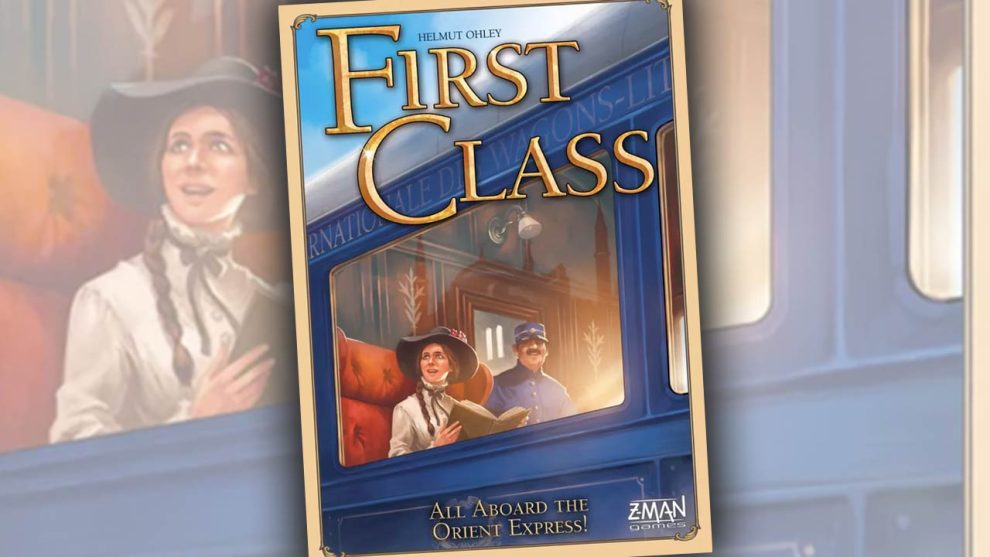

If the conversation moves from the living room to the dining room table for game night, a wholly different thought comes to mind. Instead of Dame Christie, I might think of Helmut Ohley’s railroad gem from Hans im Glück and Z-Man Games, First Class: All Aboard the Orient Express. Inevitably, even the board game forges a connection to the classic mystery, but there is much to see between here and there.

First (Class) Impressions

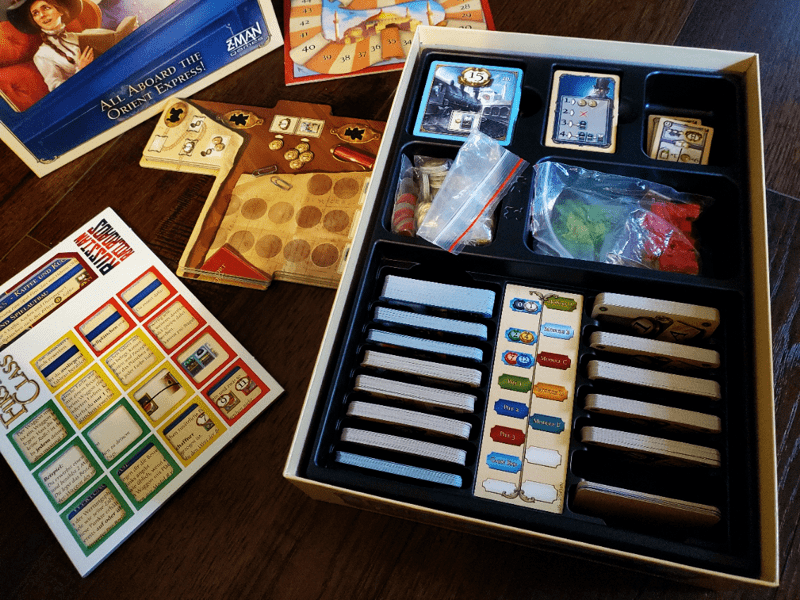

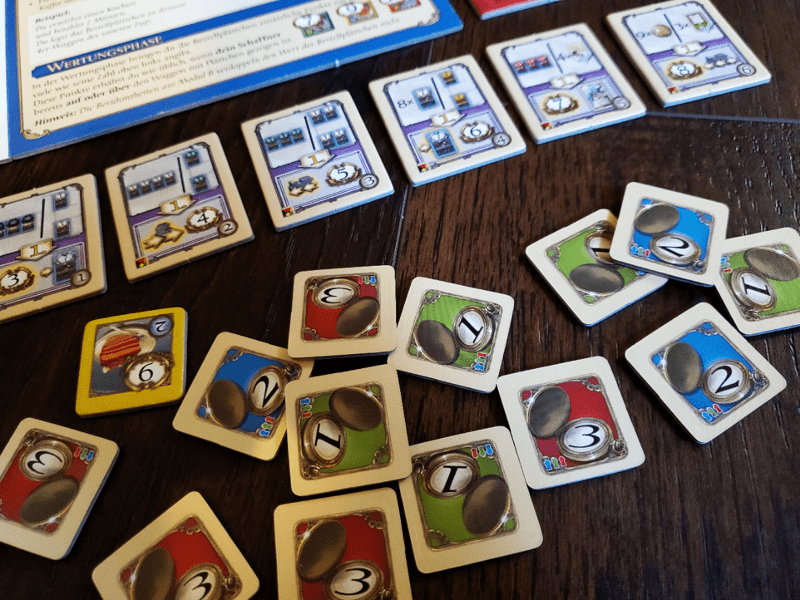

Opening the box is a bit overwhelming. Mine is a used copy—now used even more—so it arrived punched and sleeved (a problem which I swiftly remedied. There, I said it, I’m an anti-sleever). Two rulebooks, one for the base mechanisms and the other for the first five modules. Toss in the Teatime and Call for Tenders expansions and this thing is loaded. The insert is wonderfully designed to hold and organize the 327 cards, not to mention the hundreds of tokens, cubes, and meeples that round out the collection; and it is truly a collection unto itself.

The rulebook itself is thorough. Maybe too thorough. But I’ll happily welcome a bit of well-organized excess information over a gaping hole. While I understand the variety of the modules demands full pages, a player aid might have created an iced cake that would force me to rewrite this review in the form of a tender ballad.

The Engine

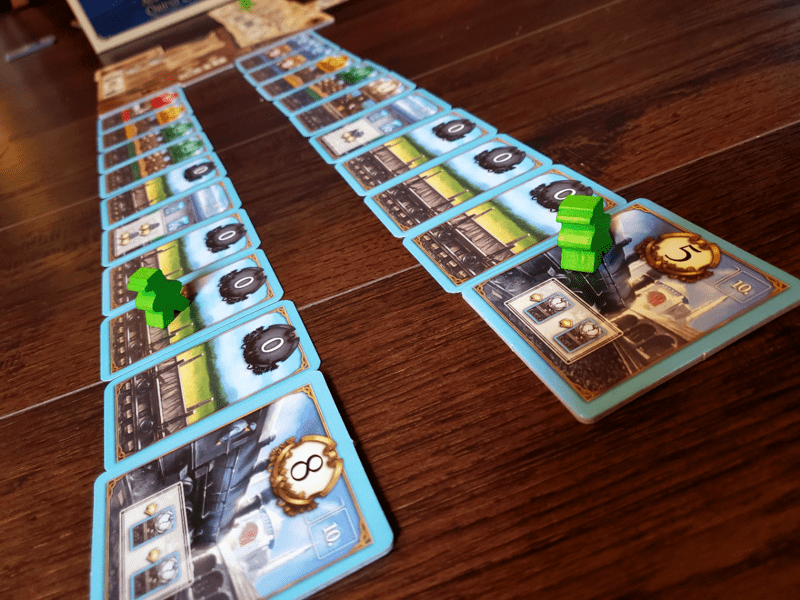

First Class is probably the longest game I own. Not in time, mind you, but in physical length. It seems harmless enough at the beginning, not unlike Santa Monica (and its far-less-efficient box), with a simple player board and a couple of rail cars. But by the game’s end, there is no surprise in having created a spread 17 cards wide. Small card tables need not apply.

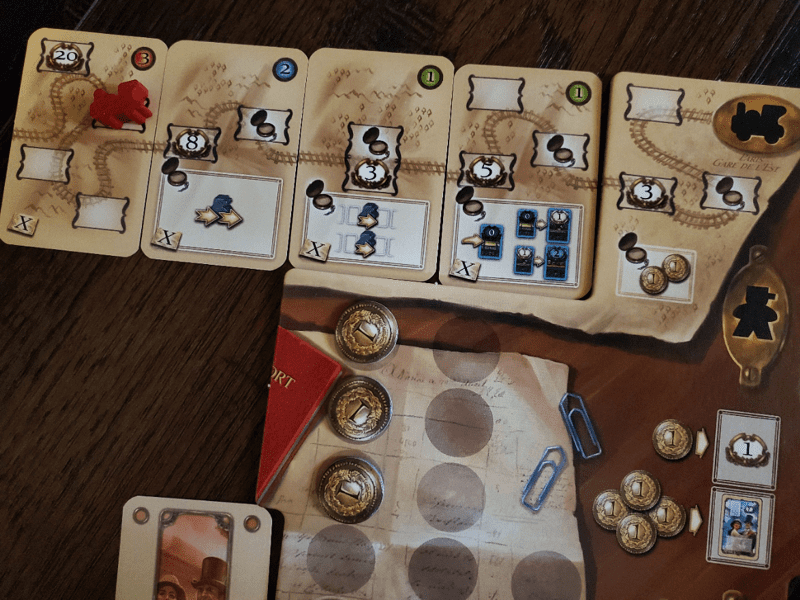

Protruding from the left of the player board, a rail map extends, inviting each player to move their Locomotive along to collect one-time point bonuses and residual pocket watch effects. Extending to the right are two trains which can span ten cards each. Conductors will travel along the cars, unlocking their point and bonus potential.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

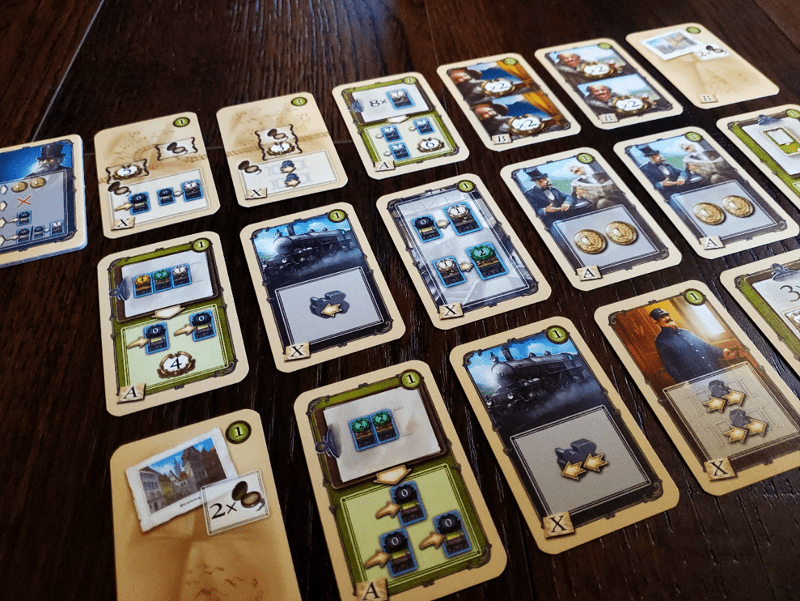

First Class is a six-round open drafting game. Each round reveals a field of 18 cards, set out 6×3 from which players will take turns selecting. Once a number of cards equal to the number of players has been drafted from a row, the remainder of that row is taken away. Therein lies the genius of this draft and a wellspring of congenial stress. There is also a first-player token which may be selected in place of a card to gain the lead and unleash a series of bonuses for everyone except the new second player—how strangely exclusive.

The field of cards is full of potential. Cards that extend and upgrade train cars, pushing the game wider to the right. (Upgraded cars must have descending values from left to right in case you were wondering) Cards that extend the map and entice Locomotive movement to the left. Cards that move the Locomotive and/or the Conductors. And let’s not forget cards from the five modules, which are described in the next section.

At the outset of the game, three decks are prepared, each with a blend of cards from the base and two modules. Think Sushi Go Party! but with trains. Each deck populates the field of cards twice with a few cards to spare, just to keep things spicy. Following the second round with a given deck, a scoring round ensues.

During scoring rounds, players first visit their train maps to trigger any unleashed pocket watch effects that have been crossed by the Locomotive. These might add train cars, move the Conductors, or award straight points. Next, players score their trains. In order for a car to score, the Conductor must have moved atop or beyond it. Conductors are always moving right towards the Engine. After the third deck expires and the final scoring round is complete, the game is over.

I should mention coins. Along the way, players are collecting coins into three columns, always from bottom to top, left to right. No matter what, coins arrive in that fashion. They are spent any way the player sees fit. Essentially, this means that the leftmost column must refill before the central column refills, and so on. This is important because each column’s coins are used for increasingly potent effects. At the game’s end, they help scoring either through the purchase of points or lucrative endgame bonus cards.

Where coins find their true value is as the fuel for wicked combos. When each player places their fifth car in either train, they immediately add a mail car, which comes with a specific bonus action. Coins in the leftmost column allow a player to buy a few cars to add the mail car which moves the Locomotive which scores points after passing a pocketwatch that will unlock more wicked combos during the scoring round. That same leftmost column might be emptied to buy the ninth car, which immediately adds an Engine/Locomotive placard which is worth points and upgrades.

The central column moves the Locomotive or one of the Conductors. Did I mention the first, second, and third Conductors to reach a finished Engine/Locomotive placard receive a fat bonus? Did I also mention that one player could conceivably grab the first two bonuses with the right lavish expense of coins?

The Cars

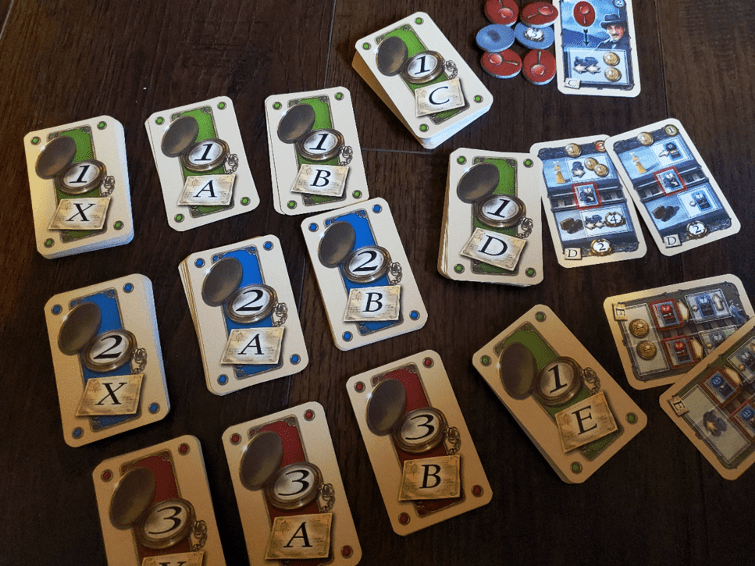

The modules are labeled A through E.

Module A introduces Contracts to the field of cards. Contracts are exactly what you might think: achieve a certain condition, gain a certain reward. Have at least six rail cars upgraded to Level 2 or higher. Have both mail cars in place. Have at least three completed Contracts. These mid-game rewards direct the drafting effort and help ease the analysis paralysis.

Module B welcomes Celebrities and Postcards to the rail cars. Celebrities are placed partially beneath a car with a tab sticking out indicating a doubled score for that car in subsequent scoring rounds. Postcards serve the same function, but they are placed beneath the map cards.

Module D is more stereotypical with Passengers and Luggage. Passengers are placed above the upper train and trigger once a condition for the car is met (most often a meager upgrade). Likewise, Luggage rests beneath the lower train and functions much the same.

Module E involves Switches and Mechanics. Switches are placed horizontally between the two trains with a condition that must be met by two separate cars, one from each train. Mechanics also ride between the trains and trigger both immediate effects, like coins, and provide additional upgrades when other conditions are met.

There are two additional Modules out in the aether which I’ve yet to acquire. Module F welcomes trinkets via Storage and Factory, and Module G lets a Magician loose on board.

The Caboose

You might have noticed that I skipped module C. Remember that Agatha Christie lady? Module C—First Class Murder—is an attempt to add bloodshed and mystery to the mix. It is also, by far, the most panned module of the bunch.

In each round’s draft, cards featuring the famed mustache of Hercule Poirot serve one of two purposes. First, they grant a small bonus and force every other player to take an Evidence token. Most of the Evidence tokens have 1 to 3 fingerprints on the bottom. A few allow for a discard of one token. A few grant bonus points. I’ll say it again, most of them are bad. Additional Poirot cards grant a much more substantial bonus, but require the selecting player to take an Evidence token.

At the beginning of the game, players receive an identity card, one of which may be a murderer depending on the player count (at four players, there will always be a murderer). At the game’s end, Identities are revealed to discover the truth about the murder. If there was a Murderer, that player receives two additional Evidence tokens before tallying the totals. The player who collected the most fingerprint icons during the game is eliminated. Just like that—taken away by the police. If the Murderer got away with it (wasn’t eliminated), they receive a massive bonus as a reward, compensation for selecting the cards necessary to hide the Evidence throughout the game. If the Murderer was caught, well, that’s good, we can all sleep well.

Some Other Cars that were Before the Caboose

While we’re talking variants, allow me a brief word about the expansions. Call for Tenders is a simple row of conditional bonuses, available throughout the game, that provide a larger reward for the first player to achieve them than every player after. Each player has two tokens to place on these rewards, but certain rewards disappear throughout the game, releasing the tokens back to the players for another opportunity. It is fairly seamless: a simple row placed out at setup and a bit of extra attention to the specific conditions during play.

Teatime introduces bonus points to various cars during the game at a cost of two coins. However, the bonuses can only be purchased for cars boasting a particular scoring level, creating another similar “strike when the iron’s hot” feel. Simple cars serve coffee. Mid-range cars serve cakes. Fancy cars break out the champagne and grand confections. This one requires a bit of maintenance during the game to set out the right tokens, but overall it is a low-intensity addition.

Does This Train Ever End?

Less than a quarter mile from my home, a train passes several times each day. I imagine reading modules upon modules in succession feels like watching the longer afternoon train pass by. Like I said, opening the box is overwhelming. But the gameplay is relatively simple to grasp. Draw a card, place it where it belongs, do what it says. No problem. Where the game takes on its remarkable character is in spotting the rich combinations buried in the decisions. Taking a card at the right moment, piling on a few choice uses of coins, unleashing massive point chains—that’s the good stuff in this box.

I adore this game on the table, mostly. It was first published in 2016, but it has such a classic feel. Michael Menzel (Stone Age, Rococo, My City) knocked the artwork to the stratosphere for my tastes. If I have a complaint about the endgame table presence, it is the inevitably high number of Zero cars on the table. It’s just not possible to upgrade everything, and it would be a strategic error to attempt to do so, but the result is a rather bland train when all is said and done. That one complaint aside, I love the ridiculously long trail of maps and cars spread all over the place. It smells like accomplishment.

Two modules are always mixed into the game decks, creating ten possible pairings of the modules. Shuffle the decks, deal them 18 at a time, leave a dozen cards hidden on the sideline every game, and I’d say you’ve got a hint of variety to entertain for a while. Certain modules will undoubtedly become favorites, but I’ve not had two games feel quite the same yet.

Because the rows clear out after a certain number of cards, the game feels largely the same with two players, three, or four. The major difference in a two-player affair is that you are keenly aware of what you were denied when the row is swept away. The number of cards drafted remains the same, and the goals don’t really fall out of line.

But the murder. Modern gaming has mostly eradicated the need to eliminate players from contention, even if it happens in the final ten seconds. So I understand the primary complaint against the infamous module C. And I will say, the two-player game is essentially ruined by this module. One person will be stricken. Where’s the fun? Why labor for so many points just to be handed a victory because the other player happens to be a sloppy criminal?

At four players, on the other hand, our friend module C isn’t all that bad, provided everyone at the table knows what is going on. I would never use module C with a first time player. I would use it with a group of friends who know and love the game and decide to welcome a little mur-dah to the game night. It’s the most gimmicky module, and the one that will see the table the least; of this I have no doubts.

As for the other modules, I can honestly say I enjoy them equally. Contracts are classic and give the game a well-established feel. Celebrities cannot be ignored if they are in play—doubled cars are just too valuable. Passengers and luggage are curious because they don’t always demand attention, yet they are invaluable for a mid-game boost. Switches and Mechanics are perhaps the widest departure from “normal,” but they force a different sort of attention to the trains that I appreciate.

Strategically, because there are endgame bonus cards, there are reasons to overemphasize either the map or the trains. But I’ve yet to see someone go all in on one—and I mean all in—and win. First Class requires a bit of attention to keep things even. There are opportunities for spite-drafting as a defensive play. There is a reason to take the first player marker instead of a card, sticking the new player two but rising to the top, especially in the four-player game. The two expansions maintain that same tense interaction as important bonuses are gobbled away. In short, there is plenty to think about in this box, and there are plenty of configurations in which to think.

First Class quickly joined the ranks of family favorites. Our gaming friends immediately fell in love with the combo-tastic play and the charming presentation. I am on the hunt for those last modules. They’ll fit in the box, and even if they are as divisive as module C, they’ll be worth a game or two for exploration. In the meantime, anybody need a few hundred sleeves?

Add Comment