Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Ex Libris: Revised Edition is a missed opportunity, correcting the original’s skin-deep flaws but no further.

Ex Libris: Revised Edition is a game that peaks at university, getting looser and duller with every passing round.

Ex Libris: Revised Edition has such a strong theme and central puzzle that its problems are mostly forgivable.

Mostly.

To Start at the Beginning

You’re a librarian, looking to win the local librarian contest with your liberally stocked library of lively library books, some of which are liable to be literary liabilities.

To win, you want a collection of books arranged stably over three shelves in alphabetical order. But you don’t just want any old books: your library should be full-to-bursting with the judge’s favourites and your own specialism, have minimal banned books, and an otherwise good mix of the game’s book categories. The player who best satisfies these six scoring criteria wins.

This is the heart of Ex Libris, and it beats strong. Since all your book cards must be placed orthogonally next to other book cards, the first half of the game is spent estimating where to place cards in the hope you don’t block any future scoring opportunities.

I’ve got a ‘J’ card already on the shelf and a great ‘M’ card in my hand, but playing it now will rule me out from playing any ‘K’ and ‘L’ books for the rest of the game. Is it worth the risk?

These are the types of decision that permeate every turn in the first half of the game, persuading you to hold on to cards for just a little longer, or play them and potentially hamstring your future-self.

Predictably, the second half is spent cursing your past-self for your mistakes.

It’s rather wonderful, buoyed by one of the most intuitive and relatable settings I’ve encountered in a long time. Organising books on shelves turns out to be a widespread pleasure (although no one I’ve spoken to organises their books by title). Add in the quirky and occasionally genuinely funny book titles and it’s hard not to fall for Ex Libris’ charms.

It reminds me of Sagrada. In both you’re arranging dice/cards in a grid, navigating awkward placement constraints, satisfying scoring criteria and hoping to avoid painting yourself into a corner.

However, whilst the way in which you get dice in Sagrada is elegantly restrictive, the multitude of ways in which you collect and place cards in Ex Libris are anything but.

Ex Libris is not an elegant game and after the first couple of rounds it’s as restrictive as an all-you-can-eat-buffet.

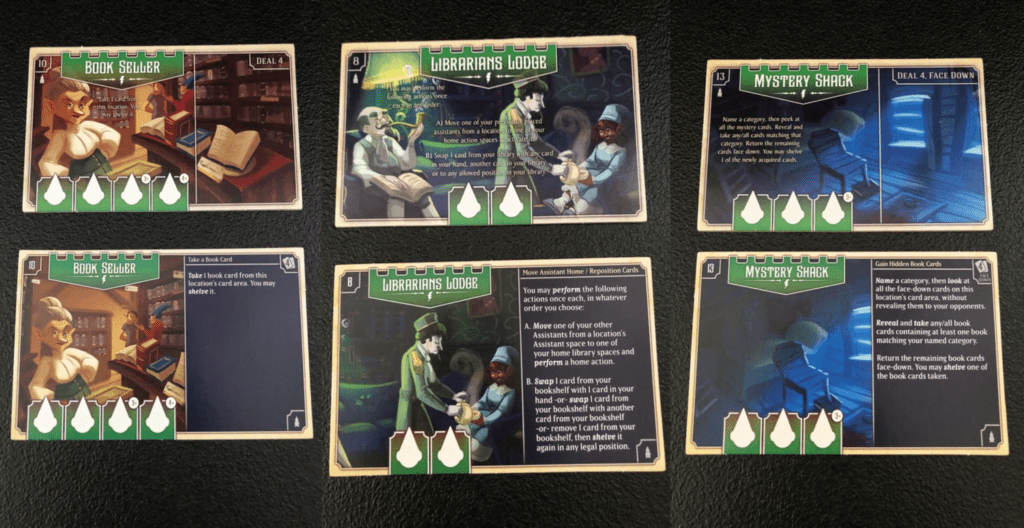

Each player has three assistants and on their turn places one at a central location or their home library. Generally, these allow you to draw cards from the deck or place cards from your hand, with the central locations being more interesting and powerful than your home library. Ye Olde Book Shop lets you swap out a card from your hand and shelve it, the Garbage Dump has you digging through the discard pile, whilst the Auction House sees players bidding for a lot of cards, and so on.

Yes, it’s that age-old gamer-favourite: worker placement. Personally, I find many worker placement games a little stagnant, but to its credit Ex Libris deals with this with gusto, cycling through the 18 different locations during the game, with one becoming permanent each round.

This I like… until I don’t.

There’s no cap on the number of locations that can be in play and the latter stages of the game become overwhelmingly cluttered.

By themselves, multiple or multiplying action spaces aren’t a bad thing. Just look at A Feast for Odin’s 61 action spaces, or the growing player-owned spaces of Lords of Waterdeep. But in both cases what each space does is crystal clear.

For a game about books, the location text of the original Ex Libris was ironically illegible. The Revised Edition is far better, but the text is still too small and overly wordy. Having to squint at a spread of 8 or more of the things that change every round is deeply frustrating. It’s rare I argue for more iconography, but either that or some strict editing would have helped here.

Beyond the legibility there’s also the fact that as the game progresses there are more and more spaces available. They’re all different but largely all variants on collecting or placing cards. Any tension and energy created by players competing for spaces quickly dissipates. More so than most worker placement games, the worth of each location comes down to the specific needs of individual players. What starts as opponents jostling each other at locations to nab the best books quickly loosens to players just passing each other in the street as they go about their separate businesses.

That core puzzle of where and when to play book cards also becomes less interesting as the game goes on and your options narrow. Whole swathes of the alphabet become off limits, or at least costly to play, so you can end up effectively just dismissing half the cards on offer. It’s more focused, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but less fun.

In ‘Beginner Mode’ Ex Libris: Revised Edition is hugely relatable, delightful and occasionally brilliant but suffers from issues of accessibility and overstay.

Standard Mode

Which brings us to the ‘Standard Mode’ and the four special assistants included in the Revised Edition.

Experienced players of Ex Libris will notice that four is considerably less than the 12 special assistants included in the original edition. The remaining eight plus an additional three are now packaged in the Expanded Archives expansion, which we’ll deal with later.

Normally I might baulk at the reduction of gameplay. In this case, I applaud publisher Renegade Game Studios’ decision, both because it means they can reduce the price and because I’m not overly keen on the special assistants as used in ‘Standard Mode’.

Special assistants replace one of your three standard assistants, and each comes with its own ability, from moving books around to bullying other players. They’re quite fun and occasionally speed the game along by providing extra opportunities to play cards to the table, helping the overstay issue.

But they vary so considerably in what they enable and the frequency with which players use them that they’re strangely isolating. While Bill is busy budging books with his wizard, all you can do is watch and wait for your turn when you’ll hide books or whatever. It’s not that they’re not interesting, but when to use a special power is often painfully obvious. I’m not sure they justify their existence. They’re fine, the meeple are cute and you might get more of a kick out of them, but for me they’re an occasional variation rather than the ‘Standard Mode’.

But…

Let me tell you how they’re used in the Expanded Archives expansion.

Expanded Archives – Jobs, Artifacts and a Fifth Player

The Job Faire module adds another 11 special assistants (as well as repeating the four from the base game). Whilst you can use them in ‘Standard Mode’, you shouldn’t because the new location tiles are far more interesting. Everyone starts the game with three standard assistants, but from the very first round onwards you can now hire special assistants to replace your standard ones, permanently or just for that round.

In many worker placement games the number of workers you have increases during the game, either through your own actions (think the ‘Wish for Children’ spaces in Caverna) or just as the game progresses (Everdell, for instance). This creates a satisfying arc, letting you feel more powerful as the game goes on. With Expanded Archives this arc is achieved by specialising your team rather than expanding it.

The result is a game with special powers that feel special because you’ve chosen and paid for them. It’s so much more fluid and interesting. By the end of the game everyone might have three unique assistants, messing about with the basic rules of the game to achieve their own book empire.

It’s a shame there’s still a weird thing happening with keywords. Someone in the design and development team is obsessed with keywords yet doesn’t know how to use them. Keywords are ubiquitous and useless. Even in ‘Beginner Mode’ the efficient use of keywords would have significantly cut the amount of text. But with the special assistants it’s absurd. Each has its own keyword (the Trash Golem ‘Recycles’, the Ghost ‘Possesses’) which is written on the assistant’s card and then explained on the reverse (and included in its own definition). It’s then never used anywhere else in the game. There’s already so much small text in the game, the inept use of keywords adds rather than reduces.

The Artifactorium module adds new trinkets and knick-knacks that you can shelve alongside your books, giving you special powers and new ways to score. The Foul Vowel Towel, for instance, scores you points for any vowel cards on your shelves at the end of the game, whilst the Alliterative Alligator lets you shelve a second card of the same letter as one you’ve just played.

Remember how I said that the heart of Ex Libris is the puzzle of placing cards to create your library? The artifacts quicken the beat. It’s not a shot of epinephrine, more like the flutter of flirtation, enticing you with interesting possibilities. Some of the artifacts are a little situational based on how you’ve already stocked your shelves, but you cycle through most of them during a game and I can’t say it’s ever bothered me.

It’s a shame that the explanation for each is on the reverse of the cards (meaning you have to look under them when you inevitably forget what they do) but it’s the right decision since they look fantastic on your shelves and, like the book cards, are a delight.

There’s no escaping the fact that both modules add to the volume of text and the general clutter of the game. I’ve groused enough about this already, but what I will say is that they’re worth it even if my interest in the assistants/artifacts offered by the new locations wanes in the second half of the game.

The final thing the expansion adds is components for a fifth player, which not only extends a game that tends to go on a little long, but also removes the ‘banned books’ scoring criteria and with it the joy of balancing the positive and negative elements of each card.

There are better games for five players.

Expanded Archives is a great expansion. It doesn’t fix the flaws of the base game, but it provides enough that those flaws, whilst more noticeable, are fractionally less frustrating. Crucially, the Expanded Archives expansion is backwards compatible with the older edition of Ex Libris so players don’t need to buy the base game all over again.

Epilogue

It’s a tricky one. I love elements of Ex Libris but find other parts genuinely tiresome. The increasing clutter and needless text puts me off. Give me a couple of hours and I could halve the word count of Ex Libris and its expansion. I’ve been kicking around an idea of a maximum number of locations available at once, with new locations being added and older locations discarded each round. For me that might keep the interesting changeable locations aspect without losing its focus.

What I hope to illustrate by telling you about a potential house rule is that there’s so much that works. It’s hard to overlook its missteps, but I’m willing to keep trying to find the version of Ex Libris that doesn’t get in its own way.

Tellingly, the decent solo mode starts the player with 6 central locations, removing 2 and adding 1 each round. Whilst it probably wouldn’t work for the multiplayer game, it invigorates the worker placement aspect of Ex Libris, creating tension and compelling challenges through its shifting and shrinking selection of locations.

The writer Stephen King has a rule when editing the first draft of any novel: cut the word count by at least 10%. The effect is to concentrate the experience, removing anything superfluous to the book and creating a stronger and clearer piece of writing. Despite this being the ‘Revised Edition’, it’s clear King’s rule hasn’t been applied to Ex Libris. There’s a Pulitzer Prize winner somewhere in this design but some ruthless editing is needed.

Add Comment