A Brief History

I have a rather large game collection. Too large, by some estimates, but that is another topic. The point is this: I do not have a large collection of train-based games. I have played several, from the old crayon-rail games to more modern offerings. I like a few of them, find others to be tedious. I guess what I am trying to say is that this is not a theme I seek out.

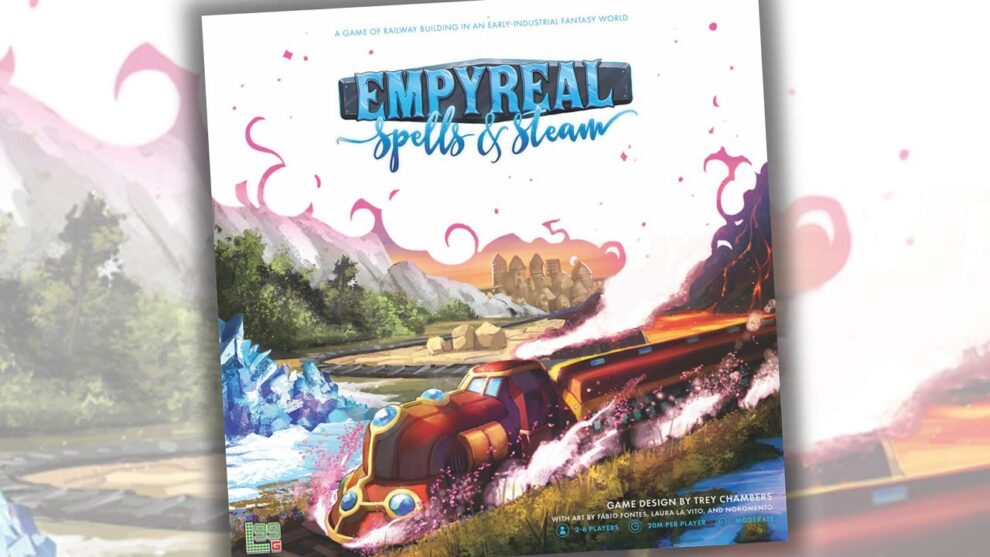

Before I started writing for Meeple Mountain, I was (and remain) a fan. One of the first things I ever experienced on the site was an unboxing of Empyreal: Spells and Steam. This video (and the others that followed) introduced me to the core game, the expansion, and the deluxe edition upgrade. I went from that unboxing video to ordering the whole kit-and-kaboodle!

So let’s take a look at this fantasy world train game, set in the early industrial-age and see what we have here, shall we?

Spells and Steam

In Empyreal: Spells and Steam, you have a magic-filled fantasy world that is just entering that glorious period of industrialization that is the age of rails. You have cities that demand goods, you have a landscape peppered with those goods, and you (as a fantasy-era rail baron) want to get those goods from the scattered landscape into the cities. Do this better than your opponents and you will find yourself triumphant!

Is this different from other rail games, you ask? Does it offer something new? The answer is yes: this is different, and it does offer something new. And the first thing it does is offer a ton of variability from game to game. No two games are the same, thus creating a tremendous amount of replayability.

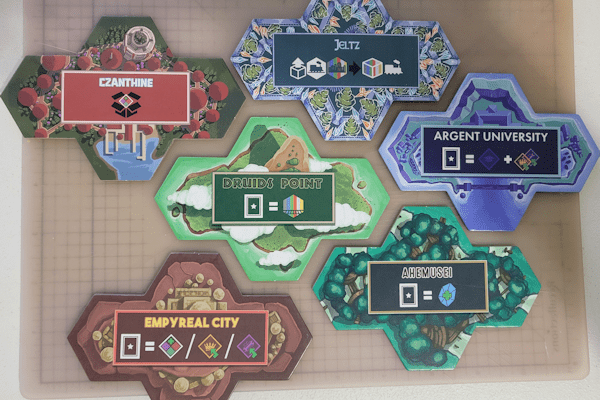

First, there is the game-board/map. This is modular and set up in a way that ensures that things do not look the same from game to game.

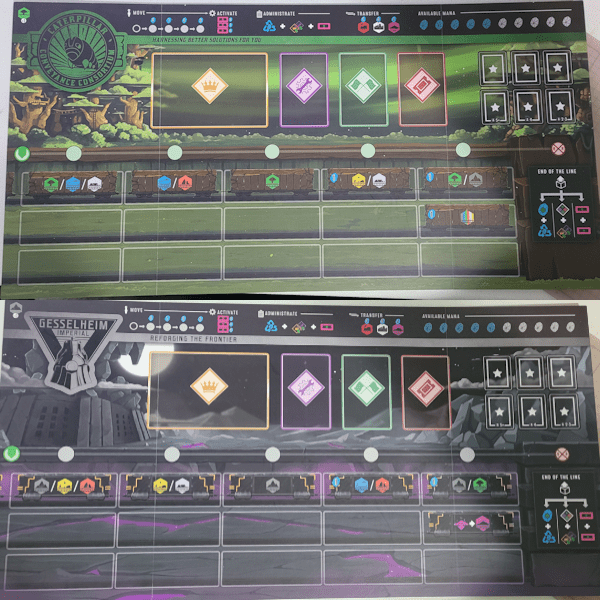

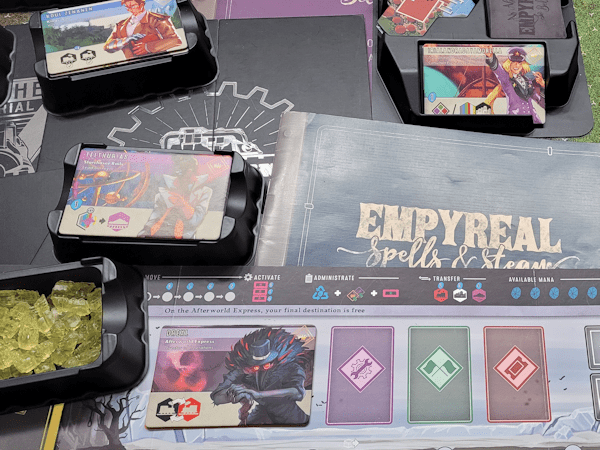

Second, we have the various companies—this is an asymmetric game, with each faction having a different focus. Not only do the companies have a captain with different abilities (and players have the option of using one of the two free-agent captains instead of their standard one), but the starting train cars (called spellcars in this game) emphasize the focus of the company as well.

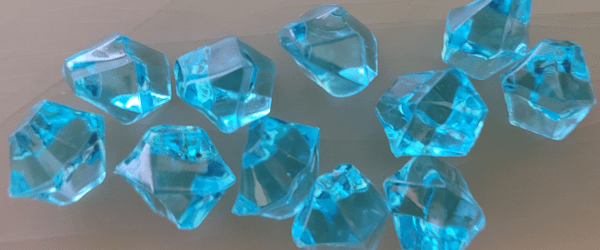

Some abilities, be this the captain, some other specialist you hired during the game, a particular spellcar, or your desire to do something such as activating more than one spellcar in a turn, will cost mana crystals. Each player starts with five mana crystals; they can acquire more as the game goes.

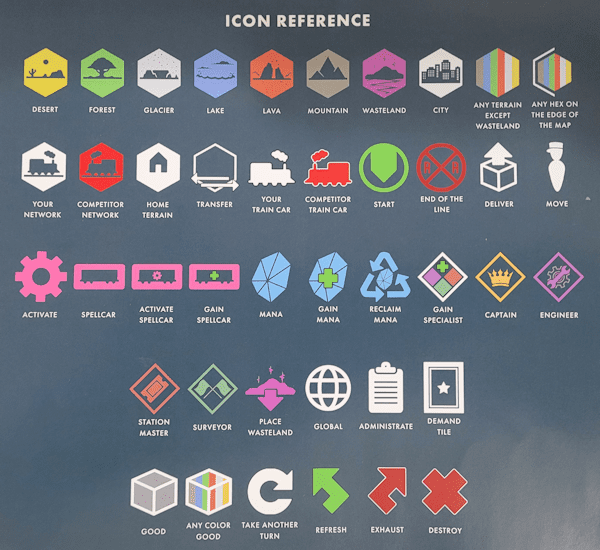

The map is made up of six primary terrains (i.e., desert, forest, glacier, lake, lava, and mountain); there is also a wasteland terrain, but this one is a bit special. Each primary terrain has a good it contains, although wastelands do not. Each city on the map has a particular good they would like delivered to them, and if you can meet the higher demands of that good in a single delivery, you can get bonus points.

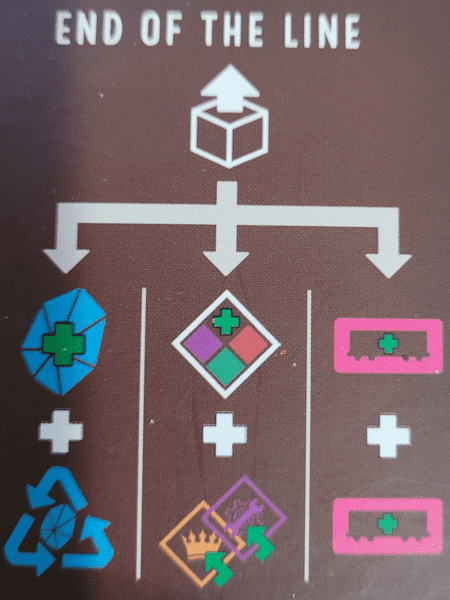

What you can do on your turn is broken into two possibilities: you can do administration (which is where you replenish your supply of mana crystals, refresh your captain, and gain a new spellcar), or you can move and activate (which is where you move a token representing your conductor along your rail yard and activate one or more spellcars in that area, or if you move to the end of the line you deliver some goods and perform one of three upgrades to your company). Moving your conductor is truly the core of this game.

On your faction mat are three rows of spellcars, with room for five cars each. You start the game with one complete row of spellcars which emphasize the terrain your faction favors. You also have one unique spellcar that accentuates your company’s focus in the game. As you acquire spellcars, they will go into the other nine slots; once those are filled up, you can begin replacing the original spellcars you started with.

The conductor starts at the far left of the rail yard, moving along the five columns toward the end of the line activating spellcars as they go. Moving one space is free, while moving more spaces in one turn costs mana. Activating one spellcar is free, activating more spellcars in that column costs mana (and some spellcars have their own inherent mana cost associated with them).

Spellcars can do many things, but the most common ability is to place trains (that is, expand your rail empire) into a specific terrain or set of terrains. Others can be used to gain mana crystals, move trains, manipulate goods, and so on. Moving the conductor and activating spellcars is how you advance your faction and reach out into new markets.

Once the conductor moves past the last column of cars, they have reached the end of the line. At that time, the player can gather up one type of good that is within their rail network and deliver those to a city that demands that good as long as they have at least one train adjacent to that city. Once the delivery is complete, the player can then upgrade their company by hiring a specialist (each one grants new powers and abilities), gaining mana crystals (allowing you to activate more powers and abilities before needing to replenish), or purchasing more spellcars (granting you more options during your turns). Once the upgrade is complete, the conductor moves to the start of the line again.

The game continues until one of two things happens: a player runs out of trains, or a player has claimed a specified number of high-demand tiles (this number varies depending upon the number of players). Once one of these things happen, players complete the round so that everyone has the same number of turns and final scoring takes place.

Spellcars, Specialists, and Mana (oh my!)

The sheer amount of variance from game to game based on the modular board, factions, captains, specialists, spellcars, and so on is tremendous! No two games will ever be quite the same.

As you expand the capabilities of your company, one of the ways you will do this is with specialists. This includes engineers, surveyors, and station masters. Each of these use similar rules, but are treated just different enough that they feel truly distinct from one another. Each game will only have a certain number of these available in the market—one plus the number of players. This means that the specialists available for hire are different every game.

The core game is quite simple. The rules take up a fraction of the modest rulebook. Although opening the enormous box and seeing layer after layer of components come out can be intimidating, I would say that after one play through anyone that can grasp Ticket to Ride should have no trouble understanding this game.

You have mana crystals, and they do power some things, but the magic is a bit more than that, and it is beautifully subtle. Mana crystals can allow you to perform more actions in a turn than you could otherwise. They can allow you to power some of the more powerful or esoteric spellcars. And so on. The game has a magical feel where the magic is a part of the world without overwhelming it.

The amount of information to which a new player is initially exposed can be a bit overwhelming. It does not take long at all for this to settle into familiarity thanks in part to the wonderful iconography of the game. The symbols are distinct and easy to read; and the back of the rulebook has a listing of those symbols and a brief definition of what they mean.

Scoring is pretty simple: 1 victory point for each good delivered plus the points for each high-demand tile acquired. Add those together and that is your score.

Advanced Rules and Options

The game offers a few options considered to be advanced rules. This includes:

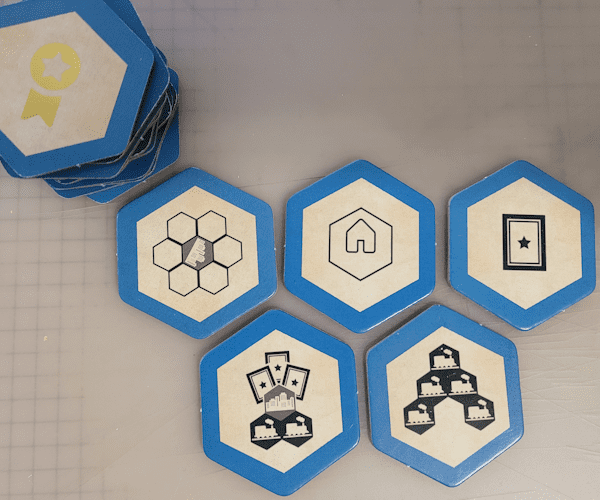

- Special goals (called Awards) can be used to grant bonus points at the end of the game for doing specific things (such as building tracks near cities that have no remaining high-demand tiles). The initial rule for the goals is to select two at random and use those. An optional rule (for the optional rule) is to draw one goal per player plus two. Then, each player in turn removes one until just two remain.

- The market for specialists is not public knowledge. Until you go to hire a type of specialist, you do not know what specialists are available. One optional rule is to make this market known at the start of the game.

Each of these is a very minor tweak to the game. The goals/awards are minor enough that I am not really sure why this is an optional rule or listed as being advanced. it really should just be the way the game is played, period.

Expansion: As Above, So Below

The expansion adds:

- Two new factions (for a total of 8).

- One new captain for each faction (for a total of 16 dedicated captains). At the start of the game, after you have selected which faction you want to play, you can choose either of the captains for that faction, or one of the free-agents.

- Metropolitan Cities. These large cities take up four hexes and comes with a specific set of rules that govern its play. This includes three Metros that add new components to the game when they are used: two Metros have spellcars only available when they are present; a third adds a whole new type of specialist you can acquire.

- With the new factions, the expansion has rules for playing up to 8 players (although the Metros cannot be used with more than 6 players).

- The expansion includes rules for solo play.

- New awards and specialists.

Overall, the expansion is well worth getting.

The Deluxe Upgrade

The deluxe upgrade box has replacement faction mats for all eight factions that are much thicker and made to look like a financial portfolio. This alone is worth the upgrade price.

The tokens used for the goods are replaced with plastic replicas (as seen in the pictures in this article).

There is an art book with some very nice larger renditions of some of the amazing artwork in the game.

And there are postcards from each of the Metro areas. These are cute, but (like the art book) have no in-game function.

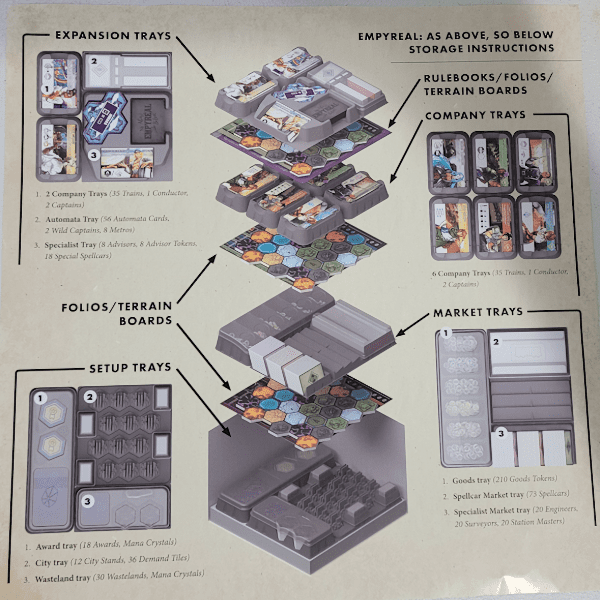

The Box

Some of my colleagues like the game (some approaching how much I enjoy it), but they complain that the box and the inserts are, well, let’s just say ‘over-the-top’ (I believe one used the word ‘ridiculous’ to describe them). I can see where they are coming from, but I disagree. I find the inserts useful and the box (and storage) to be easy to work with. But, if you are not me, you might disagree—so I thought it best to be up-front about this aspect of the production.

Conclusion

Empyreal is a wonderful game; I have been really enjoying it. It is fun, easy to grasp, and the strategies are not immediately obvious, creating some great thinky moments in each game. The variability of the game is something I have barely scratched the surface within the plays we have had… so we look forward to what we will discover each time we play. I highly recommend this game.

But it is not without its flaws. These flaws are not enough to warrant bringing this down from a 5-star game, just some things to note. The first batch have nothing to do with the rules, game play, or what-have-you. They have to do with the production of the game. And considering that Level 99 Games is trying to push themselves as a premium brand, this is a disappointing fact. Most of these are exceedingly minor flaws, certainly, but they are a distraction from an otherwise near-perfect board game experience. They include:

- The backs of the spellcars have significant variations in the print color from tile to tile. Given how these are shuffled and stored, this is not as serious as it could have been.

- Much of the game is keyed and linked using color. Lake spaces (for example) are blue; the goods that come from lake spaces are blue; the city that has a demand for lake goods is marked with a blue pattern; the high-demand tiles that go with lake goods are various shades of blue. The same is supposed to be true for desert/yellow, forest/green, glacier/white, lava/red, and mountain/black. So it is rather disappointing that the use of color is not consistent.

- On some elements, the mountain/black is printed as mid-to-dark gray.

- The deluxe goods for the mountain/black spaces are mid-to-dark gray.

- On some elements, the glacier/white is printed as light gray.

- The deluxe goods for the glacier/white spaces are pink (for some reason).

- The deluxe goods for the lake/blue spaces are mid-to-dark gray (and almost the same color as the mountain/black goods).

- The iconography for the goods, the images in the rule book for those goods, and the deluxe goods do not match. At all.

- This issue with color extends to some instances of the icons. The printing of overlay elements on icons representing a terrain type (e.g., the track indicating that you can build on that terrain) is sometimes done in black, sometimes done in white, and sometimes done in what appears to be transparent. It is just odd to see this variance.

- My copy of the core game came in a heavily damaged box. My copy of the expansion has four severely damaged wasteland tiles. I contacted Level 99 Games and they sent me a replacement box and replacement wasteland tiles. In the email exchange, it was indicated that I was certainly not the only person with these particular issues. This was a large project for them, and several production issues certainly crept in. The replacement items were in perfect condition.

- And so on…

The things that are rules and game play related are also minor, but annoying. They include:

- The goals/awards include objectives that are mirror images of each other or even mutually exclusive. I truly believe that these tiles should have been made double sided so that when you draw the random goals you select a random side of that tile and thus, in a given game, no two mutually exclusive objectives could be selected.

- The goals presented are not generally objectives that would cause a shift in play. This is exacerbated by the fact that, as a single player, you may not even have control over whether the objective is even possible: e.g., will a city have remaining high-demand tiles at the end of the game or not? Who knows? And if you have no idea if this is going to happen, how can you plan to have trains near that city or some other city?

- The first time we played, we were confused when the rules made reference to a quadruple demand tile. The high-demand tiles have numbers on them and those numbers were 1, 2, and 3; quadruple indicates a 4. It took us a few moments to realize that the tiles with the 1 have two images of the good demanded; the tiles with the 2 have three images of the good; and the tiles with the 3 have four images of the good. A close reading of the rules indicates that this is addressed, but I think it could have been made much more clear.

As I indicated, this is all minor stuff. Despite these flaws, I would highly recommend the game. I think it is a good, fun, interesting, and thought-provoking game with wonderful art and some great ideas.

Add Comment