Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

At the end of the day, the games business—like almost every other business I’ve had a hand in over a 20+ year career—is a relationship business.

After meeting Dan DiLorenzo from R&R Games at PAXU 2021, I gained a real appreciation for what it means for a publisher to hand a game—any game, really, not just the ones that are “hot” at any given time—to media members for review.

Dan strikes me as the kind of guy that I would hang out with whether we were talking shop or not. So, when I learned he would be at PAXU 2022, he was one of the only people I made sure to chat with during my 24 hours in Philadelphia.

Dan came to PAXU because he loves Penny Arcade, the team behind the PAX events. I know he loves these folks because Dan had suffered a serious leg injury the week before the event, but still decided it was worth going to ensure he could meet with customers and fans to pitch his upcoming slate of games.

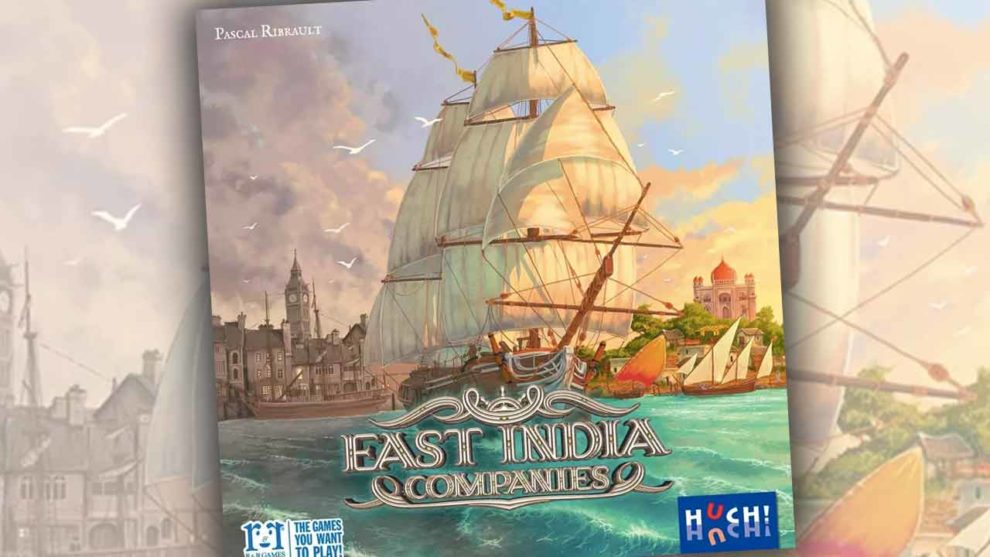

We talked for about 10 minutes before I began to walk to another appointment. Dan stopped me in my tracks. “Wait! I want to tell you about our new game.” He handed me a copy of East India Companies. I didn’t know anything about the game, so he gave me a brief overview before we parted ways.

I have to say that after multiple plays, East India Companies has left everyone saying the same two things:

- “Solid.” (Yes, everyone, sometimes separately, has called the experience “solid.” Maybe I need to diversify my network, or at the very least my love of the word “solid.”)

- “Why have I not heard about this game?”

Let’s talk about why.

Pick Up and Deliver the Equity Stake

East India Companies is a five-round, worker placement, pick-up-and-deliver stock manipulation game featuring boats instead of trains. At the end of play, the richest player wins. (Ahh, you have a game where I need to break out my poker chips? Color me intrigued.)

Players each control one of four competing trade companies—the British, the French, the Dutch, or the Swedes. Each round consists of five phases: placing Agents on various spaces to take actions, Stock Exchange, Navigation (where players place their boats on one of the three trade destinations), Loading goods onto boats, then Selling them to the European market. (The rulebook calls this last phase both Selling and Trading, but we’ll stick to Selling for this overview.)

The list of actions available during the Agent Placement step is straightforward. You can buy ships, build trading posts to lower the costs of buying goods in certain markets, take the initiative to become first in turn order, and increase the size of your dock to increase shipping capacity.

You could also dictate which goods are more or less available during the later phases to manipulate the goods market to your advantage.

Every space is open to all players every turn, with minor limitations. The action spaces are spread in a circle, and workers can only go to an adjacent action area from where they are currently based. (There is an exception to this, which we’ll come back on later.) If any other players occupy the space you want to use, you have to pay each player there a coin before taking that action.

The ship-buying spaces will likely see the most action during a game of East India Companies because boats drive everything in the game.

Each ship is ranked based on its speed and tonnage (cargo capacity). Faster boats arrive at locations earlier, which means they can buy and later sell before slower boats. Each player owns two Galleons to begin the game; each of these dinosaurs has a speed and tonnage of one. Boats become available based on the current round, so you can’t buy your Steamers until round four, but you can buy your Indiaman (speed of one, tonnage of two) or your Schooner (speed of three, tonnage of one) right out of the gates.

The succeeding phases in each round move at a brisk pace. East India Companies is a stock game, with some elements changed to streamline gameplay. That means that each player is the President of their company, and they get two shares in that company when play begins. After that, all players can buy shares in all active companies by paying the bank (not the company) for a share at its current price. This bumps that company’s stock price up a level, and the game features dividend tiers based on their share price.

At the end of each round, dividends are paid out to shareholders, but these dividends are paid by the companies, not the bank.

This is the only part of East India Companies that feels thematically off. (I’m avoiding the word “broken”, but for veterans of 18XX games or games such as City of the Big Shoulders, it will feel strange that you are not getting the investment money to better operate your company when shares are bought, then you are being asked to pay dividends later.)

After players pass consecutively in the Stock Exchange phase, East India Companies gets to showcase its talents. Picking where to send ships, buying goods, then selling those goods in a tight market is all an absolute blast.

During the Navigation phase, players take all of their ships into their hands then announce their number of ships and their speeds. In Initiative order, players place one of their boats in either India, the East Indies, or China; each boat is placed face down. Once all boats are placed, the Loading phase begins, and so does the chaos.

I’ll Take the Rest of the Tea—As Well As Your Soul

East India Companies is a pleasant, friendly experience right up until it is not. It’s also a riot when buying and selling goods gets rolling.

Just before the Loading phase, one other thing might happen during Navigation. Any player who selected the ability to choose the specific supply or demand card during the Agent Placement phase picked a card that will be revealed during the Loading and/or Selling phase. This is important because this card is added to a series of public die rolls that was conducted when the round began.

The die rolls guaranteed a certain number of goods to be added (supply) or removed (demand) from the display. In this way, players have some public information about the current state of supply and demand for the game’s four goods—tea (available from all regions), spices (India), coffee (East Indies) and silk (China). But they don’t know everything, although the back of the game’s rulebook provides information on what each goods card could add or subtract from that round’s supply and demand.

The big reveal in East India Companies is quite a moment. When Loading begins, the die rolls are accounted for first. Then all players find out how many goods will be added from the card, which may have been picked by a player or added randomly with a good shuffle of the available options.

No matter what, the same thing happens. Groaning. Profanity. “You’ve got to be kidding me”-like lines are spouted. It’s a blast, even if it serves to kill off your chances of buying any goods.

Loading begins with China. Any player who has a boat there has a chance to buy silk or tea first, based on which boats are revealed to be the fastest ones there. Speed is what matters; the fastest boat placed in each region gets first dibs on the goods offered in that region.

Tea can be bought by boats in all three regions, but there’s not enough tea to go around, especially late in the game. If a player hoped to buy tea, but sent their boats to India (India buys last, after China and the East Indies), there’s a mighty fine chance that all of the tea goods cubes will be gone when that turn finally arrives.

Plus, you guessed it: the cheapest goods go to the player with the fastest boat that was first to arrive. When four or five boats show up, you can count on some of your dreams being dashed.

The same holds true on the back end during the Selling phase. After goods that were held back in previous Loading phases are sold to the market, the fastest boats that are highest in Initiative order get to sell to the European market first.

More groans. Sometimes, screams. Some goods can be held for future rounds on your docks, but even if a market is out of space for decent prices, all goods can be sold for one coin each if there is no market for them.

Loading and Selling are the phases where East India Companies really comes to life. Profit margins turn me on. They really do. In this game, the act of buying goods and getting them to their destination for a reasonable profit is really interesting. Drama is created in a satisfying way and the loop stays fresh even after multiple plays. Another fun element surfaced in my later plays during the worker placement phase: when Agents are not located in ideal places, a player can move a worker to the center of the worker placement area, effectively passing. This led to some good old-fashioned drama in later rounds where players didn’t want to reveal their true intentions until all other players had taken their turns.

Separately, Quite Interesting

What I find most interesting about East India Companies is that its design seems to make each one of its game mechanics slightly more accessible than other peer products. It would not surprise me if the game’s designer, Pascal Ribrault, tried more complex experiences like Imperial Steam or an 18XX game, then decided to make his own more accessible version of those games.

The best example I can provide is with the boats available in East India Companies, and I’ll compare this to how trains work in 18XX games. In most 18XX games that I’ve read about or played, you start with no trains of your own as a personal investor (and once you invest in a major corporation, that corporation also has no trains). Available trains start in a common pool, and corporations have to go out and buy trains from a limited supply. Over the course of play, usually dictated by when other corporations buy newer trains, older trains “rust” and are phased out, pushing players to constantly keep up by buying newer and more expensive trains.

In East India Companies, each player has their own personal supply of the same ten boats, so no one is ever blocked from buying new boats. Relative to the game’s economy, buying new boats in East India Companies is very, very affordable. While boats can’t always be promised availability to sell their cargo—the game has to include SOME drama, right?—the front end of the operation, buying boats, is never brutal. Only two of the ten boats, the starting Galleons, can ever “rust”, and they only rust in the fifth and final round. If you are still using those boats that late in the game, you are probably going to lose anyway.

That makes East India Companies a minor surprise to me: it’s an excellent way to introduce more complex games to friends, or to scratch the itch of a route-building economy game without the route building nor the rules overhead. The teach is easy, about 15 minutes. Worker placement spots are accessible. Scores are easy to count up: cash on hand, plus the current value of the shares in each player’s possession. In my games, scores have ranged in the 125-175 range. (There’s no score sheet nor points tracker located on the board, but I’m surprised to say that this was not a problem.)

The game is not perfect. As I mentioned, for gamers of a certain age and experience, the investment in corporations feels a bit off. There’s only one English language player aid in the box (however, if you read German, I have good news for you!). The first round may tempt new players into investing at a point in the game where they will not understand the weight of that action when trying to buy goods or pay tariffs to travel to other regions with their boats.

But East India Companies is a very…solid gaming experience. That leads to my next question: why is no one talking about this game?

John Company, For One

East India Companies is about the various competitors fighting for business in the 1700s and 1800s. It only pushes a couple of historical accuracies, mainly to stick to its gameplay: the logos of the four competing firms, the names of the boats, the regions where trade occurred.

Maybe you’ve heard about a game called John Company: Second Edition, from Wehrlegig Games? That game was released to so much fanfare I sometimes have to intentionally avoid it because so many people in our space love talking about it. (I told a friend I had just played East India Companies, and he thought I said John Company even though I hadn’t said the word John. We’re still laughing about this.)

John Company is, in fact, a game about the East India Company, but takes a completely different angle to the subject matter.

I enjoy both games for different reasons, but it wouldn’t shock me if East India Companies is attempting to ride some of the historical coattails made suddenly popular by John Company. And, I get it. Selling games is important, and if naming this game East India Companies makes it more popular (particularly in other regions where this game is being marketed), that makes a lot of sense.

The game’s credits include a disclaimer, one that I use below because I feel the same way: East India Companies is a game, period. I find that sometimes, people go into these endeavors searching for a deeper meaning when one is not there. For an accessible market manipulation game that plays in about 90 minutes, I had a lot of fun playing East India Companies and I recommend it for its solid gameplay. It has quickly risen to the top of the list for my favorite gaming surprise of 2023.

Disclaimer, from the rulebook: “East India Companies is first and foremost a game without political considerations. The historical setting is only there to reinforce the mechanics, which fits perfectly with the theme that surrounds it. It deals with another time with other ‘reference points’ than ours. East India Companies is a game, a work of fiction, but in no way a documentary. And it must be considered as such.”

Add Comment