I like to harken back to yesteryore, when me and my imp brethren would dig tunnels under the cruel whip of our ogre overlord or mine for gold. Occasionally, we’d get to use a Production Room, and the really lucky among us got to use the Reproduction Room. Ah, the good old days…

Those were the days of Dungeon Lords, before the warriors, healers, and bards (oh my)! Back when imps were valued for their natural abilities. Every now and then, a lucky goblin cousin was even recruited to fight. But those dungeons shut down long ago. Frigging paladins.

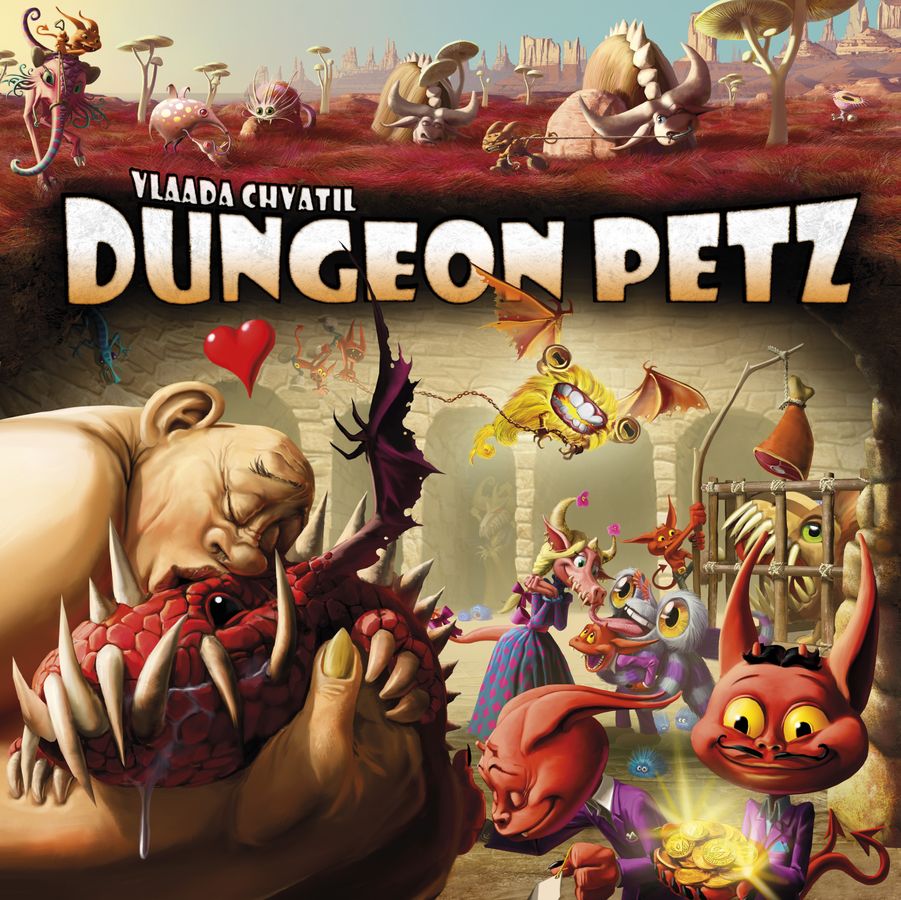

Vlaada Chvatil is a remarkable man with an unpronounceable name. His creative mind has conceived an exhaustive list of diverse masterpieces including Through The Ages, Dungeon Lords, Galaxy Trucker, Mage Knight, Bunny Bunny Moose Moose, and Codenames. I suspect he wanders through Wikipedia, clicks randomly, and designs a game from whatever subject matter displays. How else to explain Dungeon Petz?

In Dungeon Petz, players are pet store owners who purchase monster hatchlings, cage the beasts as they grow increasingly demanding, showcase the creatures to Westminster’s rejected judges, and eventually sell off their darlings to customers with specific needs and desires. No time to worry about what happens to their petz at that stage, as new younglings require constant feedings, entertainment, and cleanup.

How is this a game and not some Lovecraftian nightmare?

For starters, the petz are – dare I say – cute? While it was completely unnecessary, Chvatil provided an appendix of petz, providing the backstories for such little’uns as Snakitty, Cthulie, Wormie, and Bubl. David Cochard illustrates the game brilliantly; his doe-eyed Fluffy and Direbunny are so cuddly and adorable, it’s easy to overlook the claws and fangs and bloodthirst.

While the rulebook checks in at 20 pages, it’s packed cage-wall-to-cage-wall with illustrations and examples. As the rule-reader for my gaming group, I’m regularly saddled with deciphering convoluted instructions. Dungeon Petz’ rulebook is both thorough and logical; while there are boards and bits and pieces and parts and teeth to contend with, everything is easy to find and comprehend.

So how do you play this monstrosity?

Everyone gets a Player Board which represents their pet shop. As the previous owner of said shop didn’t give a crap about their business, they left you a rinky-dink cage with some crap in it.

The Central Board gets stocked with cages, cage add-ons, baby petz, toddler petz, artifacts, locally sourced meats and produce, potions, a track for bribing exhibition judges, a platform to showcase your wares, a hospital, and a refrigerator-worthy drawing of what my group refers to as “Uncle Charlie.”

Good gravy, that’s a lot! But I warned you a few paragraphs ago about the plentitude of bits and pieces and parts and teeth, so get used to it. In fact, there’s another board to contend with.

Okay, you think. I’ve done board games with two boards before. That’s not a deal-killer.

The Progress Board contains the round marker, the real exhibition judges, needy customers, your extended imp family members, and the end game scoring.

Three? That’s a lot of –

Your Burrow Board stores your food, gold, artifacts, and every family member you intend to put to work. It also contains handy-dandy, icon-laden references for turn order, needs and consequences for unmet needs. For those accountants among you, a color-coded breakdown of each card type stands front and center. All of the references are above the crease so you can fold your board up for the blind-bidding portion.

Now that you have enough boards to build your own pet store, play flows relatively easily. It’s a bidding and worker-placement game for action selection, so…

- Each player secretly selects family members to send through tunnels. The largest groups of imps (and gold) goes first, with tiebreakers starting with the first-player token and moving clockwise.

- Imps (groups or solo) are sent out to perform the tasks on the central board. A cage requires at least two imps, buying a pet requires you supply an imp with at least one coin, and everything else needs only an imp. You may not want to keep your family members in the burrow, as odds are high you’ll need them to perform other jobs.

- Collect everything your imps have gathered, and place your pet(z) in your cage(z). Selecting the proper cage for each pet is important, as anger and magic need(z) are fulfilled primarily with the cage’s inherent construction.

- Determine what needs your little beasts have by counting the different colors fully revealed along the bottom edges of their eggs. Draw a need card for each and every need they have. If they’re hungry, feed ‘em. (Make sure carnivores get meat and herbivores get greens.) If they need to play, send an unoccupied imp to frolic with them. If they have magic or anger needs, check your cage to make sure they don’t mutate or worse, escape. If they’re crappy, add poop to their cage. Manage that poop carefully, lest your pet get sick and suffer with a disease need.

- Once you’ve satisfied all the needs on all your petz (or suffered the corresponding consequences), you’ll have opportunities to showcase your miscreation to the judges in every round after the first. The exhibitions on the progress board include an eating contest, beauty pageant, and magic show. Sometimes, judges want to see your best individual specimen; other times they want to examine every horror in your little shop. Whoever best matches what the judges are looking for scores points on the platform (as do the bribes), and the highest scores win points.

- Each round after the first also has customers perusing the shops. If your pet’s needs match the buyer’s wants, you can sell your little darlin’ to the likes of Porky Orky or Dungeon Girl, among others. You don’t have to sell it now, though. You can keep it in your shop with hopes for a better-matched buyer. Ghosty would probably be a better companion for Warlock than Dungeon Granny. Customers can buy one pet from each shop, and in the last round, two customers will come a’callin. Sales are worth double points, or if you sell from the platform, triple.

- Imps that weren’t sent out to the central board or used to play or capture potential escapees can collect a coin or, more than likely, shovel manure. A clean cage makes a healthy pet!

- Any petz retained in your shop will age by turning the dial on their egg. This will create more needs to be met, and potentially create more needs to match judges and buyers, creating more points. And suffering. And mutations. And poop. So much poop.

- At the end of six rounds (five in a four-player game), consult the progress board for endgame scoring. The shop owner with the most points wins!

Dungeon Petz is a game stocked with frustration and rewards – there’s little chance of accomplishing everything you set out to do. Analysis paralysis can run high, and there’s plenty of risk leaving spots open on the central board. There are so many priorities, and you need all of them.

Every pet requires a cage, so buying too many petz is dangerous. Every cage without a pet is useless. In a four-player game, it’s possible that both cages and one pet have been swiped up before you send out your first imp. To guarantee you getting the specific cage and pet you want, you can overbid with all your imps and gold to get to take both the first and second actions of the round. Congratulations! You got everything you wanted! Now you have no more imps this round to gather food. No imps to chase down that angry Trolly. No imps to play. No imps to clean the cages. No imps = no good.

For those of you believing it’s easier in a two- or three-player game, Chvatil includes specific rules of a third imp family blocking spaces to sustain the tension and desperation. You can always stockpile food and cage improvements and potions, and send an extra cousin to the platform, but you have no dungeon petz to show or sell? You kinda missed the point of the game. It’s right there, in the name.

The longer you keep your petz, the more likely you are to fail meeting their needs. It’s a thing of beauty. And agony.

I admire the illustrations as they fully immerse players into the setting. The box cover and all of the boards are overpopulated with busy imps doing impy business. It’s frenetic and sets the tone for the ensuing stress. This makes it a fitting sequel to Dungeon Lords, where players perform as many actions as they can to prevent the game beating the crap out of them. Part of me is thankful Chvatil hasn’t yet considered the idea of cross-breeding petz, and another part can’t wait for that third installment in this trilogy which will probably never happen.

Dungeon Petz is silly, fun, complex, fiddly, and a game I will bring to the table whenever someone suggests it.

Add Comment