I picked up Dragon Pets three years ago, played it twice, and then put it on the shelf. To be honest, I wasn’t impressed. As I worked through my collection recently for a cull, I came across the cutesy box from Japanime Games once again. Spotting those adorable dragons and remembering (vaguely) the mechanics, I thought it might be a nice fit for my younger son and daughter, so I dusted it off and brought them to the table. We played several times, and they’ve been playing it ever since.

I’ve realized something else in this second encounter with the dragons: there’s something in this little box for the more tactically-minded adults, too. I’m not saying it’s going to gate-crash anyone’s top 10 of all time, but I was unwise to dismiss it so quickly the first time.

Dragon along

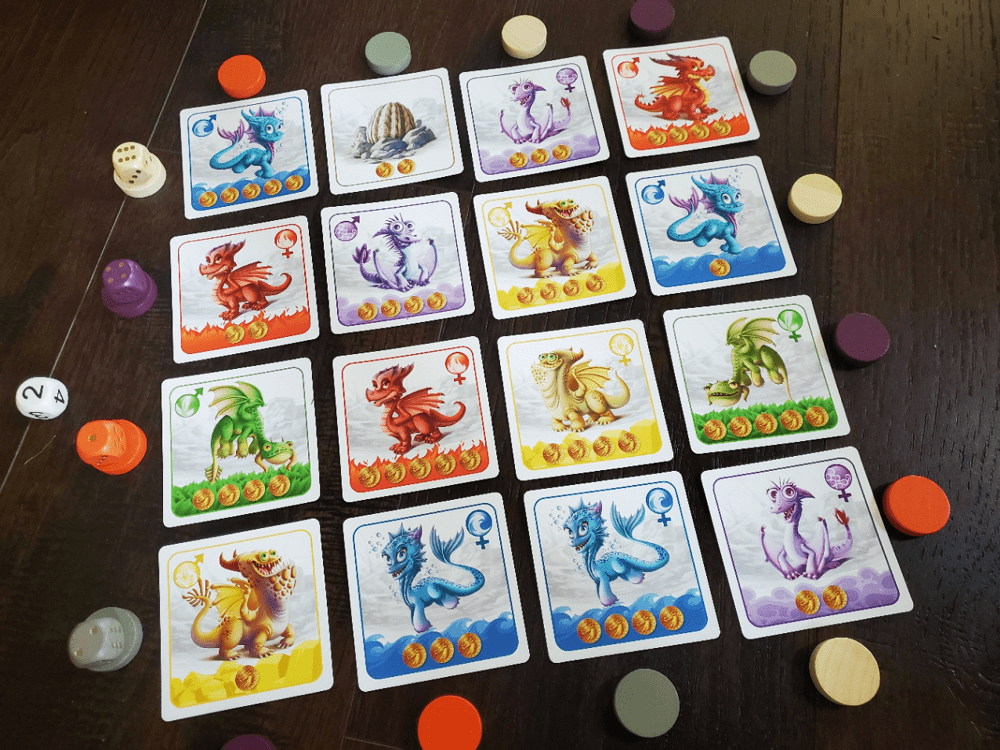

In Dragon Pets, players take up the role of dragon breeders to engage a 4×4 grid of square dragon cards. Each dragon is one of the game’s five colors and has a gender and coin value. The goal is to gather males and females of matching colors, collecting the higher of the two coin values from each pair. The player who accumulates and maintains the larger coin collection wins.

During setup, each player places four wooden discs along one edge of the grid. Each of these discs matches a wooden die in color. Each turn, players claim an interest in a dragon by placing one of their three meeples in accordance with the dice. If there is a purple three, for example, one choice is the third dragon up from the purple disc. There is a fifth, white die that serves as a potential modifier as well. So a white three might be used to turn an orange two into a five, or a gray six into a three. After a dragon is selected, the die that enabled the choice is removed from play and the remaining dice are passed to the corresponding discs for the next player.

This dragon selection is the fourth and only mandatory action available on every turn, but it behooves us to begin there before explaining the remainder of the options, as they make less sense without understanding the end. Please forgive my insubordination, but I’m going to explain the remaining actions entirely out of order, even though they must be performed in order.

The third action is rerolling the dice. This might be a viable choice if the dice happen to be terrible for you, or if the other players have removed certain desirable dice from play, either for their own good or simply to spite you.

As a first option, players might pay one coin for all players to harvest their dragons from the grid. Obviously it’s nice to bring the dragons home, but why would you want to help everyone else? Well, when claiming a dragon, it is permissible to bump a player by paying them a coin. If you really want a particular beast in your collection, the cost may be worthwhile before someone snipes it either for their own good, or just to spite you.

Secondly, if the grid has gaps from a previous harvest, players might pay one coin to draw new cards into the field. With only four dice potentially available, it is possible none of them points to a location with a dragon. In this case, players either pay one coin to refill or five coins in penalty for failure to place a meeple. It is absolutely delicious to survive a turn where six dragon locations are vacant and you’re down to only two dice, but you’re able to use one of them just to pass on the impossible situation to your neighbor out of spite.

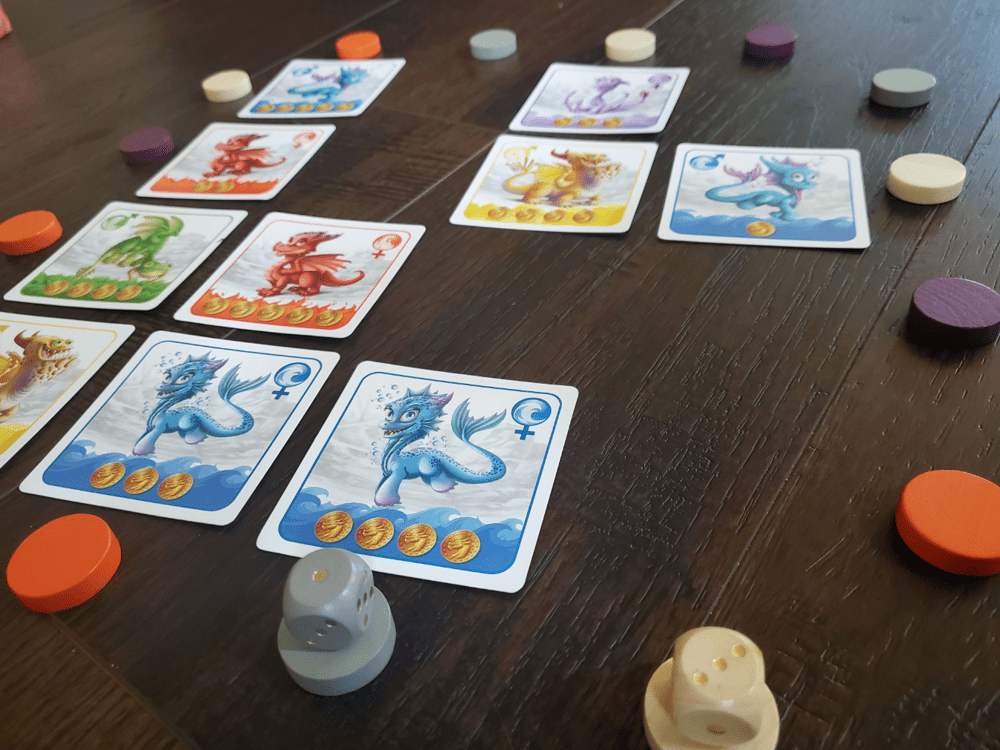

Players, then, must exercise these actions in order: harvest, refill, reroll, claim, on every turn, with the final claim being the only mandatory part. Play continues until the deck comes up short during someone’s refill action. Yes, you read that right, someone has to pay to end the game with coins, which are victory points.

There is a bonus at the end for collecting at least one pair from every dragon color. Any unpaired dragons result in a loss of the coins depicted on the card. Feeding the bonus, there are also a number of dragon eggs in the deck depending on the player count. These eggs grant two coins at harvest, but in pairs they count as a wild towards gathering the set of five. The player with the largest coin collection wins the game and vindication over the spiteful spiting that characterized the previous half hour.

Dragon my feet

Dragon Pets is a delightful little game to play with children. I get to celebrate every cute pair of dragons my daughter lays down. Sure, I could bump her from a dragon now and then, but it will be with some sort of a funny face, and she’ll simply reroll and (hopefully) bump me back before the next harvest. It’s all so adorable.

Then another adult sits to my left and the funny face goes away. Where I had previously been so peaceful, my voice in such soothing tones, I now angle my brow and bite my upper lip in plotting silence as I make every effort to pass the least palatable situation around the clock. I alter my plans, shifting to a different colored pair in the spur of the moment just to steal away what seems to be my neighbor’s most desirable card. I become an opportunistic miser, and I delight in my stingy antics.

I think I missed the Hyde side of Dragon Pets three years ago because I only played with my children. In kindness, it was void of interesting tension. And there’s a lot of fiddling with dice just to be really nice to my neighbor. The end of every turn involves passing each active die to its corresponding disc on the next side, then passing the spent dice. There’s a lot of handling for such a light experience, especially when a turn might only consist of the one mandatory meeple placement before passing the dice again.

But that mechanism is rather unique and makes for interesting decisions. The discs are fixed on each side, but each die gives the next player a wholly unique opportunity. With the reroll coming relatively cheap there isn’t much reason to calculate beyond the next player, but it is often within range to cost your neighbor at least a coin through your decisions. And every coin matters.

Dragon Pets is a game for the mindful spendthrift. The eight coins given during setup might become 20 or 30 by the game’s end. But I’ve also seen the game end in bankruptcy, which leads me to the other potential gripe about the grid. It’s possible to get caught in a rhythm—say in a three-player game—where one player pays to harvest, refill, and reroll. The next two players benefit from all those decisions, claiming dragons with two dice, eating up the modifier die, and sending the situation back to the first player, who now feels compelled to pay for the reroll. Again. It’s a vicious cycle, especially if the victims are your children.

I don’t find the same trouble with adults or more capable kids. All you have to do to break the cycle is withstand one selection, maybe even by taking away the die you know your neighbor will want, or hold off on a harvest just one more round. Of course, waiting opens the door to some of the more cutthroat possibilities for the spitefully minded, but that’s where these cutesy critters are most interesting. A little attention goes a long way.

The last few turns are especially fun as the threat of penalties looms overhead, card counting efforts backfire, and you realize you’re not going to get a mate for that five-coin purple dragon in your hand. Do I pay two coins to harvest and refill just to end the misery? There are two yellow males and two females out there…should I claim one and hope nobody else ends it? Will I even have the dice to make the match? Is it worth it?

Dragon Pets is fairly diverse and definitely more interesting than I formerly gave it credit for. It is nominally fiddly. It is occasionally out of balance. But it has potential as a shifty-eyed tactical filler. It rolls downhill to an enjoyable ending with a very straightforward conclusion.

Where I thought I was pulling out the scaly pets for their swan song, they just may have survived this cull for a bit of unexpected exploration.

Add Comment