Wednesday, July 17th, 2013 began with an alarm.

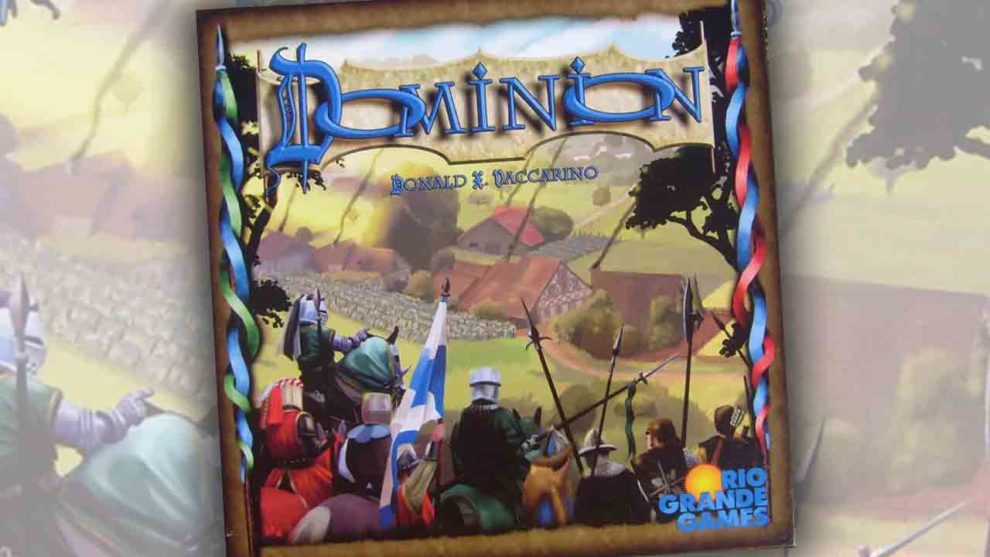

After putting it off for as long as I could, I stopped hitting snooze and finally caved in to the pressure to roll myself out of my bed. As I went through my morning routine, I had no idea that in just a few hours’ time, my life would be forever changed. That was the night that I was introduced to Dominion, an experience so unforgettable that I felt compelled to log onto BoardgameGeek to write a review of it. It was my very first review.

That was 10 years and 315 reviews ago, but I still remember it vividly. Dominion is a game that leaves its mark. The first time that I played it, I was changed indelibly.

Released in 2008, Dominion didn’t take long to start turning heads and winning numerous awards, including the coveted Spiel des Jahres in 2009. But the game owes its root to a game fifteen years its senior, Magic: the Gathering. Magic not only presented players with the components for a fully playable game, but it gave those players the ability to custom-tailor their game experience via the process of constructing their own decks from the available pool of cards.

And, boy do Magic players spend a lot of time constructing their decks! They study the meta like they were doing homework. They scrimp and save and wheel and deal in the hunt for the perfect singles to bring their deck(s) up to competitive levels. And when they sit down across from their opponent, they begin the game with confidence. Their deck is a fine-tuned machine, thoroughly tested, ready to be put through its paces.

Magic paved the way for many trading card games to come, but they all had the same tenet in common: every player should have their own deck before they sit down to play, and the cards in that deck should be interchangeable. Magic also introduced the concept of sustainable expandability. And that’s because Magic is more than just a game. It’s a game system. Its plug and play mechanics ensure that Magic is going to be around for a very, very long time to come.

Overview

Donald X. Vaccarino’s brilliant idea was to create a game around the process of constructing the deck, and that’s what Dominion does. In Dominion, every player begins the game with the same ten cards—seven money and three cards that provide end of game victory points but serve no other purpose—which they will be adding to over the course of the game.

Between the players is a market of ten different types of cards with ten copies of each. On their turns, players use the cards in their hands to acquire these cards and add them to their discard pile. Whenever their hand of cards is empty, they refill it by drawing from their deck. And whenever the deck runs out, they shuffle their discard pile to create a new deck to draw from. The net effect of this cycle is that, with each iteration, their deck of cards grows, making each turn more varied and exciting as the cards they’ve acquired begin coming into play.

The market acts as the game’s timer as well. After a certain number of card stacks is empty, the game ends. Then the players gather all their decks and examine the point-scoring cards to tally their final scores. The player with the highest score wins.

General Concepts

Before you can begin playing Dominion, there are a few general concepts you’ll need to understand:

1. You’ll begin every turn with exactly five cards in hand. However, depending on the cards you play during your turn, you may wind up playing many more cards than that.

2. Each card has a specific type—Action, Treasure, Victory, Curse, Attack, or Reaction. Of these, the first three are the ones you’re likely to encounter the most often. Actions let you do things such as draw more cards or purchase cards from the market. Treasure is what you spend to acquire new cards. Victory cards are worth points at the end of the game and can be purchased from the market; the more they cost, the more points they’ll provide.

3. On your turn, you can play any number of Treasure cards from your hand. These are added together to determine your purchasing power for the turn.

4. On your turn, by default, you are allowed a single action (playing a card of the Action type) and a single buy (purchasing a card from the market). These limitations can be extended by playing specific cards that allow for additional buys and/or actions.

The Cards

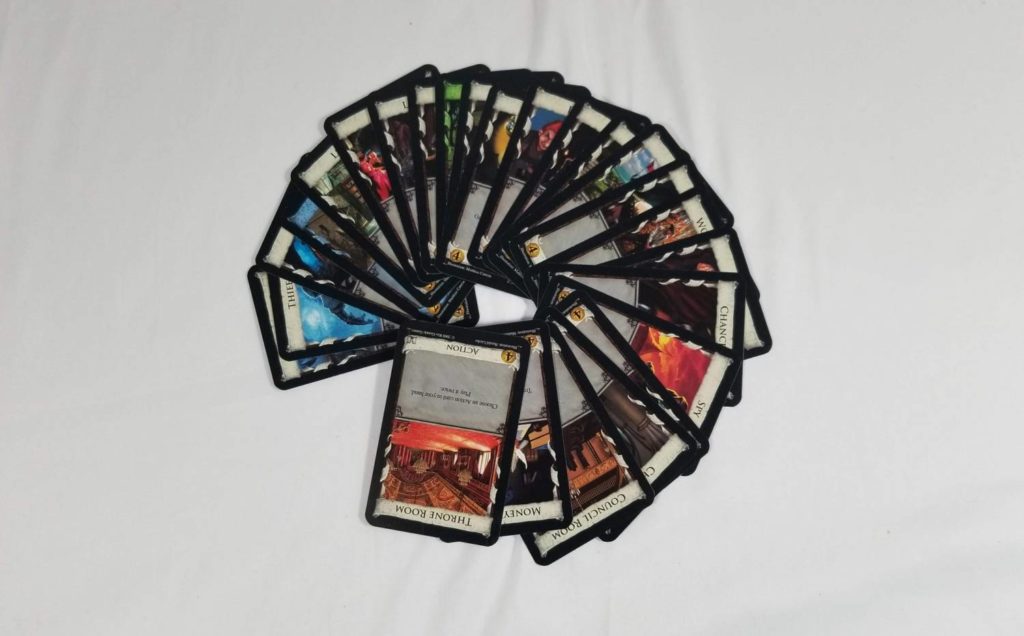

At the time of this writing, there are fifteen expansions for Dominion which, combined, add another 390 different Kingdom cards to the game, as well as new mechanics and concepts. Even without those, though, there’s still plenty of game in the base game box. The base game includes 25 different Kingdom cards, only ten of which you’re going to see in any given game.

During setup, ten of these Kingdom card types will be selected using the included randomizer cards or one of several Dominion randomizer apps (I use the aptly titled Dominion Randomizer). Or, you can simply choose which ones you’d like to play with.

In addition to these Kingdom cards, there are also going to be several Treasure and Victory cards available for purchase. The cost for purchasing a card will always be shown in the bottom left corner of the card. As these cards are purchased, they are added to your discard pile. As the game goes on, they cycle back into your hand and you begin playing them.

This is when Dominion truly begins to shine.

Every card has a unique effect. Rather than provide you with an exhaustive list of cards, here are just a few examples to give you an idea of what you can expect:

Bandit: adds a Gold Treasure (buying power of 3) to your discard when it is played. It also has the potential to force your opponent to trash (remove from game) a Treasure card they have previously purchased or acquired.

Festival: +2 Actions, +1 Buy, and +2 buying power

Laboratory: Draw 2 more cards and also get +1 Action

Vassal: +2 buying power. Additionally, discard the top card of your deck. If it happens to be an Action card, you can play it immediately.

There are also cards that will outright give you cards for free, will add negative point value cards to your opponent’s deck, or provide a way for you to trash unwanted cards from your own. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. One card specifically, Throne Room, is so complicated that it prompted me to write an entire lengthy post about how to use it properly.

In short, there’s a lot to explore. What worked in one game may not work in the next. And that’s a good thing. Dominion will keep you on your toes.

The End Game

If, at the end of someone’s turn, the Province pile (one of the Victory cards) is empty or three or more of the Kingdom card piles is empty, the game will come to an end. Every player will gather up their cards and separate out the cards featuring a victory point symbol. Most cards with this symbol are worth a specific number of points. Some provide points based on how well the criteria laid out on them are met.

The player with the most points wins.

Thoughts

I have played a lot of Dominion since that first game back in 2013 and it still holds up after all these years. It’s a fine game and I have a lot of fun playing it. But each time that I play it, it doesn’t take long for me to remember just why it was that I slowed down on it so much.

Dominion, like many strategy board games, has a problem. It has been played so thoroughly by so many players that one dominant strategy has evolved, regardless of which Kingdom cards are involved. That strategy is referred to by serious Dominion players as ‘Big Money’. In ‘Big Money’, the idea is to focus your efforts on buying money and/or Provinces and not much else. The strategy itself isn’t the issue. The issue is that the strategy is so prevalent that almost everyone that plays the game employs it. Before you know it, Dominion becomes all about either giving in and playing ‘Big Money’ or trying to find a way to beat ‘Big Money’. The other cards may as well not even exist. It’s worth noting that the game’s many expansions address this to some degree, but this is a review of the base game, and the base game just doesn’t.

Coming from a Magic background, Dominion really spoke to me the first time that I played it. I loved the way that the cards interacted with one another. I loved the idea of constructing your deck as you go. It was my first ever deck-building game and the concept was something unique and unusual. Dominion even inspired me to design my first game, an anti-deck builder where the idea is to dismember your deck more efficiently than your opponents.

But time has soured me on the game somewhat. Maybe that’s because of the ‘Big Money’ fiasco or maybe it’s because Dominion’s biggest legacy is all the games that it inspired which sprouted in its wake—games like Valletta, Clank!, Dale of Merchants, and Altiplano just to name a few—that have improved upon the ideas that Dominion brought to the table. Those games have the benefit of hindsight, a thing which Dominion never had. By today’s standards, Dominion just feels old and uninspired. When talking about the game, I have to force myself to remember that Dominion wasn’t just an example of a board game archetype. It WAS the archetype.

Taken as the progenitor of the deck-building archetype, Dominion never fails to impress. I mean, here we are fifteen years later and it’s still being expanded upon. But taken on its own merits as a game, stacked up against every other game out there, Dominion falls flat. What it does, it does well, but there are just so many others that do it better.

There’s a special place in my heart for Dominion and I’ll always love it because of that. And even though it’s not a game I find myself eager to pull off of the shelf any longer, I would gladly accept an offer to play it. Like an old friend I haven’t seen in ages that I have very little in common with anymore, Dominion and I are comfortable with each other. I’m always glad to see it.

Sometimes that’s all you need.