Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

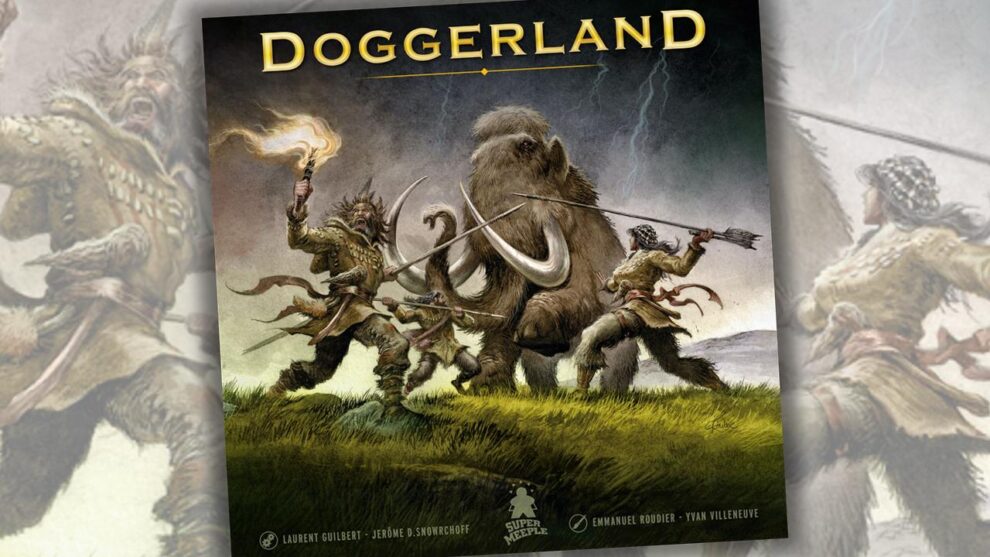

Doggerland is a reminder why certain types of game mechanics stick around—because they work. While this game is not going to blow your socks off with a completely new style of play and unusual mechanics, what it has is certainly enjoyable.

In the game, you’re at the end of the last ice age, around 15,000 years ago, in an area that is now submerged in the good ol’ English Channel. You’ve got a tribe to manage: you’ll need to feed them, hunt game, and make cave paintings. The setting is similar to Endless Winter: Paleoamericans, a game that I reviewed a while back, and if you’re familiar with the “get food to feed your people” style of game, you’ll find a lot familiar here.

Doggerland takes place in 5 phases. The first player walks each player through these phases on their player board, and each one of them is designed to be executed with surgical precision. First, you “program” which is the game’s terminology, and is a bit of a stretch. You’re really just placing your tribe members as workers around on various action spaces, paying a small upfront cost in some cases, nothing in others. You don’t execute the actions until phase 3, hence the programming, but a bit more on that in a second. The actions are standard fare—go gather different resources from specific spaces (though your workers can only haul back a certain amount, so you need to make sure not to over-harvest), hunt big game meeples, make cave paintings with animal meeples you’ve previously hunted, make various arts and crafts for variable amount of points, have babies (more workers), build more houses to house said babies, and use a special shaman piece to do super-once-per-game actions like teleporting across the board and taking first player.

The big limitations in the game are the previously mentioned carrying capacity of your workers, and distance from your tent. At the start of the game, each worker can only carry 2 resources back, and you can only gather two spaces away from your tent. As you upgrade your abilities (it’s an action you place workers on) you’ll get more carrying capacity and distance capacity.

Most interesting are the big game meeples. There are four kinds, and each kind requires you to have a certain level of know-how (a virtual value threshold that you have to meet by having enough tools and worker brainpower) to be successful. Plus, big game produces a bunch of different resources, and often, unless you’ve brought along your entire village or upgraded a ton of technology, you won’t be able to carry it all back.

After everyone has completed placing their workers, the map automatically adds new tiles to edges where players have placed components, opening new resource spots and new opportunities. In Phase 3, everyone simultaneously executes all of their actions in any order they want. This is likely why they refer to it as programming, though you’re typically going to be just doing specific actions first so you can have the resources required to do others. It’s do A so you can do B, which is technically programming, but it’s not particularly sophisticated.

In phase 4, the animals that weren’t hunted follow an automatic sequence, moving around the board, which is a neat little feature, and in Phase 5, players feed their villagers, have food spoil, and move their tent around the map, changing the spaces where they can gather.

At the end of the game, you’re going to score points for the huts you’ve built, the various crafts you made, there are more points for villagers and cave paintings, and a small majority competition for the most cave paintings done in a row in the cave painting display.

There are a couple of small features that really add to the experience, at least in my case. The game alternates between summer and winter sequences, and during winter, everything has extra costs. You can lose points if you can’t pay some of these costs, but the winter/summer alternation adds some nice moments and feelings of scarcity.

Adding to that scarcity is the fact that resource areas become unavailable after being used twice in a 3/4 player game, or once in a 2-player game. You have to keep running your village around the board, hunting and gathering in the truest sense of the word. You’ll never have a slick engine running because, well, engines and farming haven’t been invented yet.

All-in-all, the game is well-designed, if lacking a bit in player interaction. A shared board usually gets me excited, but the board grows large, and eventually there are enough resource spaces that there isn’t really a battle for terrain, and most of the interaction boils down to the typical worker placement motif of “you took my spot!”

But, it’s well-crafted, and if you enjoy a challenging puzzle with some novel mechanical flourishes and excellent components (par for the course for Super Meeple) you won’t be disappointed. Now, go hunt a mammoth.