A Brief History

I do not recall the first time I played this game, but I do recall loving it for years and years. The best sessions of Diplomacy were while I was in the Navy. We had a six-month deployment, so what we would do is handle the game one move per day. Players had a 24-hour window to secretly negotiate and scheme with each other: and scheme they did!

One person (usually me) would collect the orders from each of the players; at a designated time set so we could all be there, we would run through what took place, adjust the board. Everyone would crib down notes on who was where and then disappear for a few hours. Phone calls would take place. People would meet for lunch or midnight rations. And then, within a couple of hours of game time, I would start getting visited by players as they turned in their orders. One game we played on the USS RANGER lasted over two months. Given that two moves in the game is one year, in that game World War I lasted over 30 years.

Diplomacy is a wonderful game… if you have the right people.

The War to End All Wars

Imagine Chess where, instead of the cycle of “you move – I move – you move – I move” the game was organized such that you commit your move, as do I, and then both moves are revealed simultaneously. Based on the results of those moves, you then calculate what you want to do next and commit your move, as do I, and so on. Repeat this until the king is trapped or captured.

This is a fair description of the base mechanic for Diplomacy.

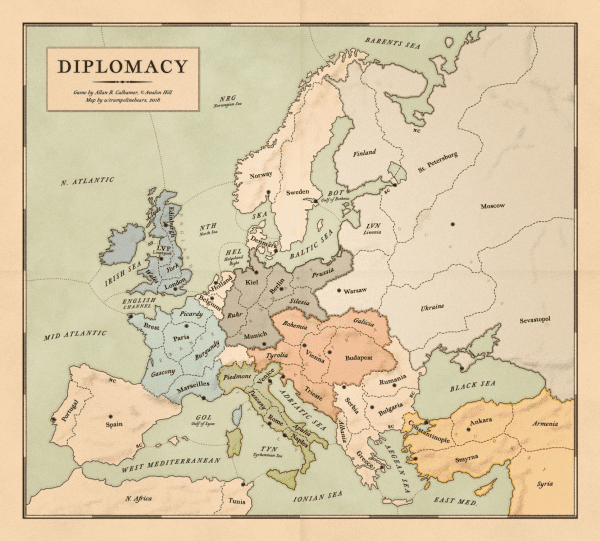

Each player in Diplomacy is one of the seven major powers in Europe just prior to The Great War (World War I). Each player is given three units (four for Russia) which are located on various supply centers on the board, within the initial boundaries of the nations they are defending.

Units are simple: they are either armies or navies. Every unit has exactly the same strength and the same movement (one space). Navies can obviously traverse the seas; they can also control coastal areas. Armies are limited to the land, but can move inland where Navies cannot exert any control.

Outside the borders of the various nations are the areas of contention. These are minor powers, smaller nations, etc. They also have supply centers—which is good, because this is what you are after. The total number of units of military you can support at any given time is equal to the number of supply centers you manage to keep control over.

Players spend some time scheming and talking. They make plans for working together in the next turn, but the deals they make are not binding! Players will often find that their orders all fail because the people they were counting on did not follow through. Then, on a set schedule, orders for the units are turned in. Nobody knows for sure what will move where until the orders are revealed. One by one, orders indicate moves, support, naval convoys, amphibious landings, and so on.

The rules for conflict are simple: First thing—no dice, no cards, no randomizer of any kind. The game uses no luck-based elements at all. No more than one unit may ever occupy a space. If two units attempt to move into the same space, barring any support, then they will bounce off of one another and not move. If one of those two units has support from another unit that is capable of moving into that space, then that unit now goes into the space with an advantage and can occupy it. If both units are supported equally, you are back to the standoff position. Navies can occupy and support within coastal regions. They can also be given an order to convoy an army over the seas.

Any order other than a move/attack order can be canceled due to being attacked. For example, if a Navy in the North Sea is due to convoy an army, but is attacked, then the convoy order is canceled as it defends itself. Same for support. If a unit is ordered to support a movement into a region, but is itself attacked, then the support order is canceled while it defends itself.

Players move their units (Spring), then move their units again (Fall). After that, each nation counts up the number of supply centers it controls. They will then adjust their unit totals to match this number. They may get to build new Navies and/or new Armies to aid in the conquests. They may have to disband units that can no longer be supported. This is called Winter Reinforcements.

At the end of any Winter, if a player controls 18 or more supply centers (that would be more than half the supply centers in Europe), they win.

The War to End All Friendships

Diplomacy is strategic thinking and charismatic negotiations embodied into a simple set of rules that result in some complex and deep game play. It is, perhaps, the purest of all war games. And for that, it deserves the long-standing respect it has had for 50 some-odd years.

But as I said in the beginning of this review: Diplomacy is a wonderful game… if you have the right people. And therein lies the rub. People that are emotionally sensitive, easily upset, or have difficulty separating the alliances within the game from the friendships outside of the game need to avoid this one. Nothing will put a strain on a friendship like having a support order you thought was coming withheld, or a convoy order you were not expecting take place. I have watched people get amazingly angry in this game—not at the game, but at the player that they had bargained with when that bargain turned out to be a red herring.

This is one of those games that also brings out the true Meta Game in some people. What I mean is this:

Suppose Andy and Bob are playing Diplomacy. During the game, Bob double-crosses Andy. This may be a significant turning point in the game; it may be a relatively insignificant move; it may have not even worked. It really does not matter. What matters to Andy is that Bob double-crossed him. Skip forward to a different board game sometime in the future. It does not matter what game it is. But Andy does something in that game to royally screw over Bob. The move may not even help Andy in the slightest, it just messes up Bob something terrible. Bob gets upset. He asks why Andy made that move. Andy smiles, and says “Remember that support order I was supposed to get in Berlin during that game of Diplomacy three months ago?” Seriously. I cannot tell you the number of times I have heard conversations just like that. I even watched as two close, lifelong friends came to blows.

Granted, this is a player issue, not a direct issue with the game. But this game certainly brings it out in people. Be careful!

So why does Diplomacy bring this out in otherwise reasonable people? Personally, I believe it has to do with the nature of the negotiations and the orders. In a game of Risk, for example, Bob (above) might double-cross Andy in the same way. But when Bob does this, Andy sees it and can adjust his plan. In Diplomacy, everything Andy did that round was dependent upon trusting Bob to be his ally. There is no time or ability to adjust. Andy is just plain screwed—and he is so because Bob looked him in the eye and assured him that they had a plan.

There are very few games that allow such a maneuver. This maneuver is at the very core of Diplomacy.

Conclusions

Diplomacy is a great game. I can recommend it—to the right people. I rate this game a 4 out of 5 stars – but that comes with a rather large asterisk! Your game group needs to be able to handle it. Unfortunately, you will not know if you can until you have put your closest relationships to a very stressful test. Go forward with caution.