There are a lot of reasons that Chinatown, a game originally released in German in 1999, has since been reprinted twice in English. It’s a solid, fun negotiation game.

There are also reasons that it hasn’t gained the world-wide fame that games like Monopoly or Catan have. It’s only fun if you enjoy trading or negotiation. Additionally, its theme of playing as a Chinese immigrant to 1960’s New York drips with racist stereotypes, so you’ll find yourself slightly uncomfortable if you pay any attention to the theme, whether you’re culturally sensitive or uncomfortable playing as another race. (There’s no option to play as a 19-year-old Donald Trump.)

In 2019 and on, should you buy/play Chinatown? Read on for an overview of the 2019 Z-Man Games edition’s gameplay and artwork, as well as my thoughts.

Gameplay

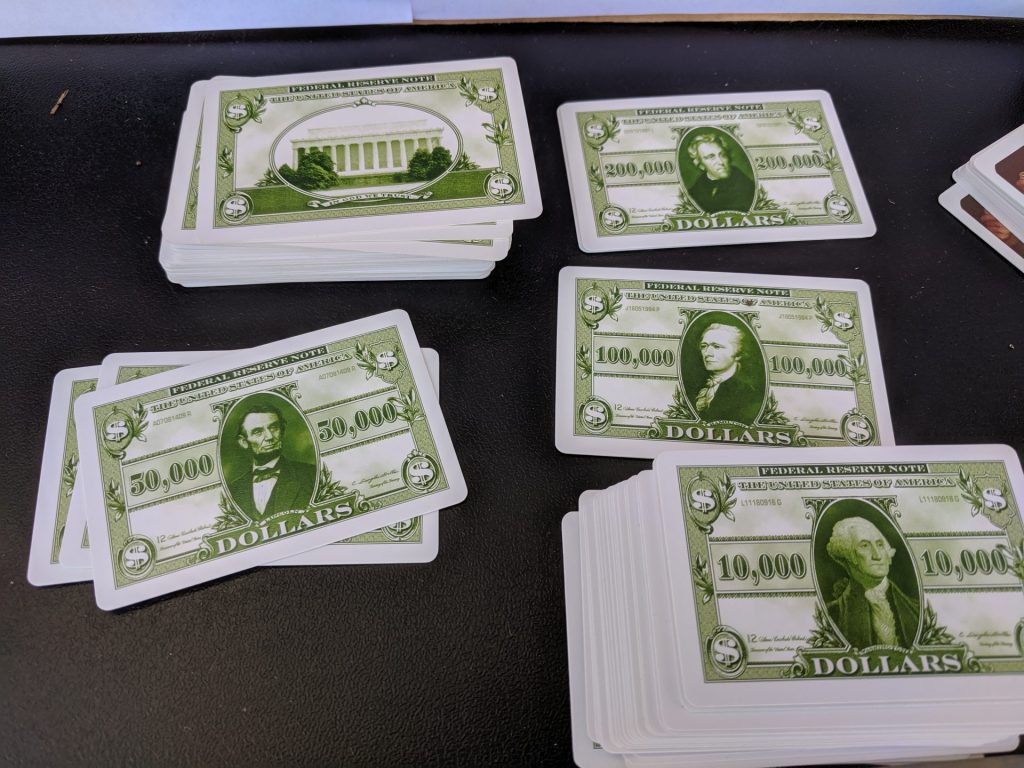

In Chinatown the winning objective is to acquire the most money. Players are Chinese immigrants to 1960’s New York with the dream of owning an empire of large income-generating shops within Chinatown. Each player starts with $50,000. There are 6 rounds of play represented by the years 1965 to 1970.

This Drives the Market

During each round, there are 6 phases:

- Dealing Building cards

- Drawing Shop tiles

- Trade

- Placing Shop tiles

- Earning Income

- Move the round marker

During the Dealing and Drawing phases, everyone acquires an equal number of building lots and shop tiles depending on player count. The first phase of dealing Building cards allows for choice – players do not get to keep all the buildings they were dealt – but drawing Shop tiles is purely luck of the draw. At least for the first turn, players will end up with more shop tiles than building lots to place them on.

The Trade phase is the core of the game, but your motivation to trade is driven by placing Shop tiles and earning income.

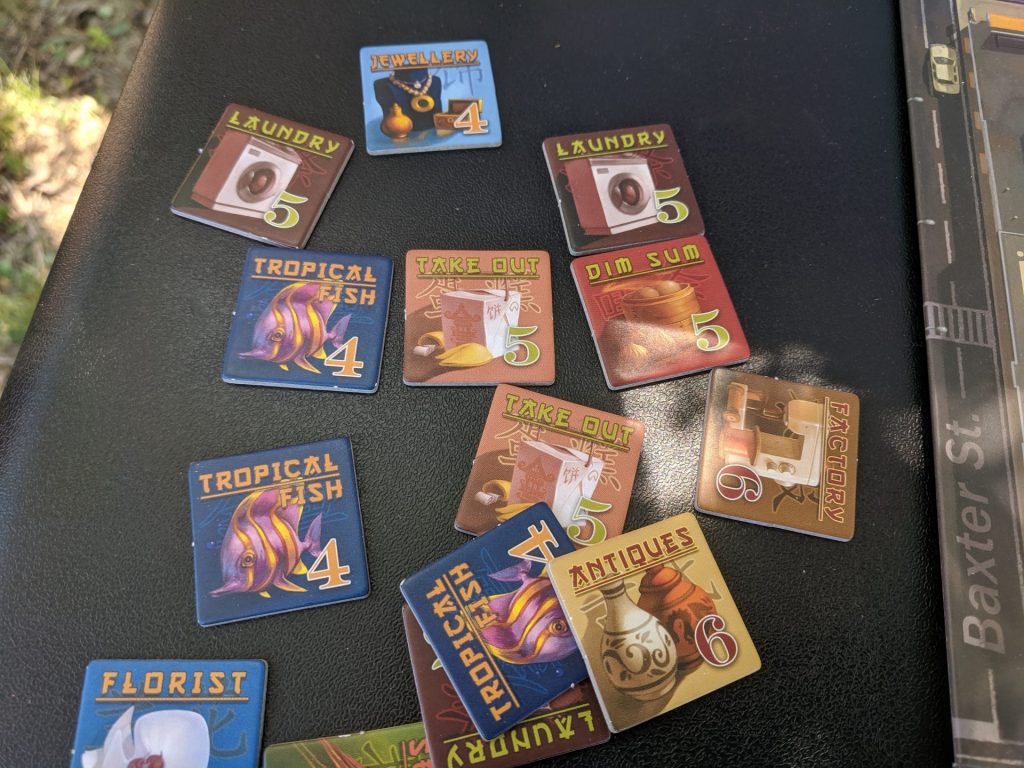

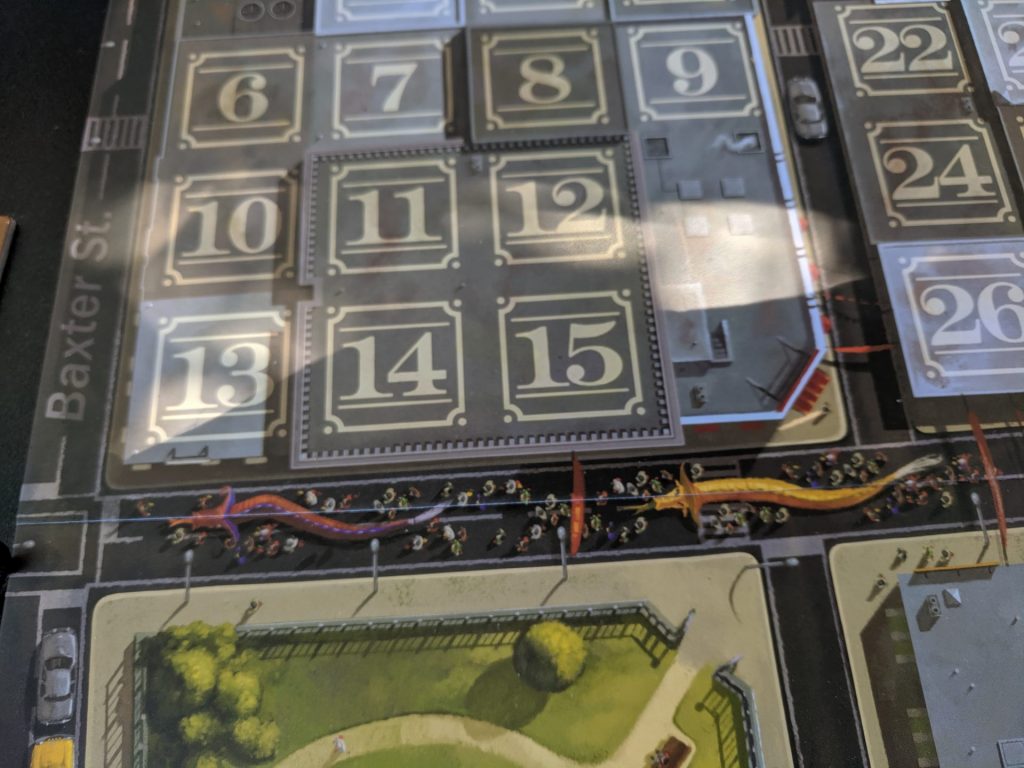

During the Placing Shop tiles phase each player places as many of their shop tiles as they wish onto any of their building lots they choose on the board, along with an ownership marker. (Important note: a placed shop tile may never be removed.) Building lots are indicated by numbered squares on the board arranged in blocks which represent Chinatown. Shop tiles are comprised of various types of businesses such as Restaurant, Laundry, Tropical Fish, etc. Shop tiles also have a number which indicates their maximum business size. Players will aim to place identical shop tiles adjacent to each other until they have reached their maximum size, which generates maximum profit.

During the Income phase players receive money based on the size of their businesses created by adjacent shops on the board. A completed business earns significantly more money than an incomplete business of the same size.

This IS the Market

This can’t be said enough; the Trade phase of the game is the most important phase and defining feature of Chinatown. As the rulebook states: during the Trade phase, “Anything goes!”

Most trades involve unplaced shop tiles, building lots, building lots with placed shop tiles, and money. “I have this Flower Shop which you have one on Lot 44, I’ll give it and some extra cash to you for the Restaurant [which I have 3 of already].” “Give me Lot 29 for these two Seafood tiles, we’ll both be making the same income as a result!” Trading money is an interesting quirk as well, since in Chinatown, money is the only thing that counts as “points” at the end of the game. You’re literally trading points for the prospect of future points.

More ambitious and dangerous trades involve trading something now for future promises. There’s nothing built in to enforce such a trade and no rules preventing you from finding a way to enforce it either. You might get away with breaking a future promise but is it worth trading on your reputation? Maybe!

Other than the rule regarding not removing placed shop tiles, there is no other rule regarding trading. You want to trade some gum for that shop tile? Go ahead. You’ll mow my yard for all my building lots? Sure, why not?! These kinds of trades probably don’t happen often, but I love how possible they are.

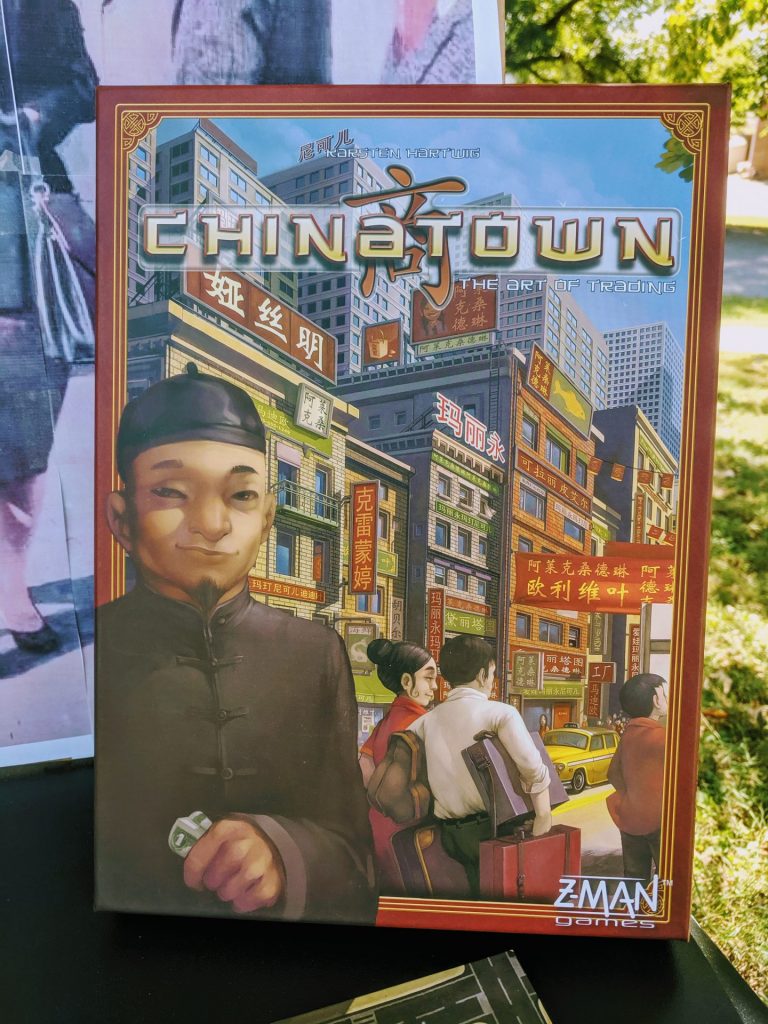

Artwork/Components

The box of the game is titled Chinatown with a tagline of “The Art of Trading”; I’m going out on a limb here to say it’s riffing on Sun Tzu’s Art of War. The box art features tall buildings with Hanzi (Chinese characters) signs and a few people depicted with some typical Western stereotypes of Asian appearance-squinty eyes and mandarin collared robes. When I browsed the web trying to find photos of Manhattan’s Chinatown from the 60’s, all I could find outside of news reports of holiday festivities was a photo depicting both Chinese and Caucasians dressed in the typical American style of the time–suits with hats and dress jackets with skirts.

The board displays the building lots with a top-down perspective along with a few scenes of activity: a car crash, a parade with Chinese dragons, and roaming taxis. The shop tile types are also stereotypical: Take Out depicted by the traditional white box for Chinese-American food, Laundry, Tropical Fish, Antiques depicted by vases, and Tea House, just to name a few.

All of the art is well done for what it depicts. I’d say not legendary artwork – reminiscent of textbook artwork, but more pleasing than such and even better than most comic books.

Components are a plastic year/round marker, thick cardboard for shop tiles, plastic round markers for ownership tokens, and thin but stiff cardstock for money and building plot cards. Practical but nothing to write home about.

Thoughts

I’m not going to start by telling you how great this game is, and why you should or shouldn’t buy it. Ordinarily I’d try to convince you to buy any game I love, but it’s already off the main retail market, for the second time. You’d have to buy it from some shady third party who has it marked up far too high. You might try to to buy my copy but I don’t think you’ll make me an offer that convinces me to sell. Let me tell you why…

Chinatown provides a remarkable environment to trade within. It’s not overly complicated: each player has a chart detailing exactly what the income will be with what they own.

At any given point you can determine what income you are guaranteed to earn from an immediate trade. For the shops with the lowest maximum business size, that’s likely to be the total. However the larger businesses and the random drawing of more plots and shops each round shake up the long-term math into relative uncertainty. The downside is that luck of the draw does impact final scoring – this is not a game for those who want to win on pure skill. The upside is that skillful negotiators aware of basic statistics will succeed more often than not.

There tends to be more friendliness involved despite the very direct competition. The randomness of the draws means you need trades to survive. Make an enemy too soon and your trades may dry up. Waiting for a trade to be more valuable may work out to your benefit, but may equally help the rest of the table instead. Trading with someone usually benefits both players, so there’s incentive to make a deal valuable to both of you, now.

All that to say, the gameplay of trading and is a ton of fun to anyone not put off by wheeling and dealing negotiation.

So what’s the problem?

The problem is the theme and the artwork. Frankly, it disturbs me a bit. The theme of this game is merely adequate to get the concept of gameplay across; it doesn’t get in the way, but I believe it could easily be swapped out for a multitude of other themes or stories. There is nothing about the history of 1965 New York’s Chinatown that drives the gameplay of this game. Unfortunately, the history of Chinatown and the stereotypical depictions are more than adequate to misrepresent and be offensive.

I found myself wondering why a German designer in 1999 would theme his game on 1965 New York Chinatown. It was probably convenient at the time and probably not recognized as offensive to the majority culture back then. Which leads me to wonder if Z-Man put any thought into it when they reprinted Chinatown in 2008, 2014, and now again in 2019 (when cultural sensitivity is high).

You can play the game and ignore the theme and artwork, and have an absolute blast. I get such a thrill from making a good solid deal, especially when I can make it seem like the other person is getting a better one.

So…you still want my copy and think you can convince me to give it up? I got “lucky” and picked up my copy for a bit over $50, but it’s out of stock again and I’ve seen some copies available for $100+. There is one way I’d be willing to give up my copy. Convince Z-Man Games to retheme and reprint a version of this game and I’ll let you have my copy for free.

Do we have a deal?

I thought about going to Chinatown for dim sum this weekend but now realize how much I’ve been relying on, and perpetuating, offensive racist tropes. Thank you.

“I found myself wondering why a German designer in 1999 would theme his game on 1965 New York Chinatown.”

Here is the answer from the Designer:

It´s so incredible; The Orginal Game by Alea takes place in New York in the middle of the 30´s after the world economic crisis with the “rebuild” of news shops … Take a look to the old Alea Cover.

I never really noticed that the Filosofia crew change it to the 60´S.

Thanx for your nice review 🙂

The Designer

P.S.: Where are my 5 Bucks ??? Or are they gone, cause my english is so bad, or cause I´ve found this Artikel so late…

keep on playing, keep on having fun!

Thanks for the additional information! Frustrating for publishers to make changes without consulting the original designer first. Again, great game, so thank you for designing it!

For the $5, you do accept Chinatown cash, right?

“Unfortunately, the history of Chinatown and the stereotypical depictions are more than adequate to misrepresent and be offensive.”

I’m an Asian, a Chinese descendent, and I don’t find anything about this game offensive at all. Maybe most, if not all, Asian would agree with me on this. We love tea, we love Dimsum and we love trading!!

I would find it inappropriate if it showed a naked squinty eyes Asian or a Caucasian dressed in suit on the box of the game titled Chinatown. You know, something that really misrepresented what Chinese were. As for the game, I’m thinking about getting one because I feel like my dad will connect with the game through the theme and culture, and he’ll get hooked on broad games.

Thank you so much for your review.

I often find it concerning when people vehemently assume there would be offence taken by others. It often strikes me as quite condescending and sometimes really quite iffy. Like assuming because someone is a minority they are somehow more sensetive and acting like representations of their culture isnt just as likely to be understood as celebratory and positive as something negative.

Are you saying that traditional asian dress is something to be ashamed of? That parades with dragons in the street is something invented by white people to opress? Are you assuming the game is pushing some stereotype that asians are bad drivers?

Why be insulted on someone elses behalf when that could be just as insulting? Why be ashamed of liking a game about people trying to make it in an interesting and thematic time and setting. I dont see the problem att all.

“Stereotypes” exist for a reason…because those tend to be the most visible actions, dress, entertainment, food, etc. for a given people group. But they become stereotypes when people outside of that people group use those things as the only defining thing about that group. So, do Chinese people dress that way _sometimes_, yes. Do they have have parades with dragons, yes. But to continually use those as examples of what defines a Chinese person is what might bring offense.

But to address your last question…if I’m not part of a specific culture, then I can’t know for sure when something is deemed offensive. But I should listen when THAT CULTURE says when things are offensive, and I can then call those things out when I see them used elsewhere. Based on your name I could potentially assume you’re a white man, living in the United States. Do you like it when people from other countries might assume that you’re a fat, loud-mouthed, rude American if they came across you (because that’s one of the stereotypes of Americans)?