If you’re a eurogame designer, odds are, somewhere in your game there are going to be contracts of some kind. It’s the Mount Rushmore of resource management mechanisms. You gotta have something to do with all those bits and bobs you’re collecting. The exemplars: there are games with bespoke contracts that you acquire for yourself and only you can do (La Granja, Yokohama, Imperial Steam), there are games with contracts that everyone is fighting to complete first (Nucleum / Barrage style), and probably a zillion other ones that I’m forgetting.

But then, there is the fraught category of the positional contract. This style of contract is, funnily enough, more genealogically related to hidden role games than it is the classical euro point-converter.

Hidden figures

It goes like this: there’s a condition that the game state needs to be in, and when it is in that state, you can get points and/or win. In a hidden role game, your team needs to be winning or losing, or the game needs to be in a precarious position for your exciting reveal to clinch a win. You need to conduct the player orchestra to get the necessary conditions for your win. That’s why people keep coming back to games like this, and why games like Clans are still widely beloved.

The positional contract is the eurogame version of the hidden role, and its execution lies at the heart of Chandigarh. There’s a reason I’m devoting so much preamble to this concept, because this game shoots a mechanical arrow directly at the problem that positional contracts create. Unfortunately, it ends up re-rehearsing the exact pratfall that the mechanism has.

Moving and plopping

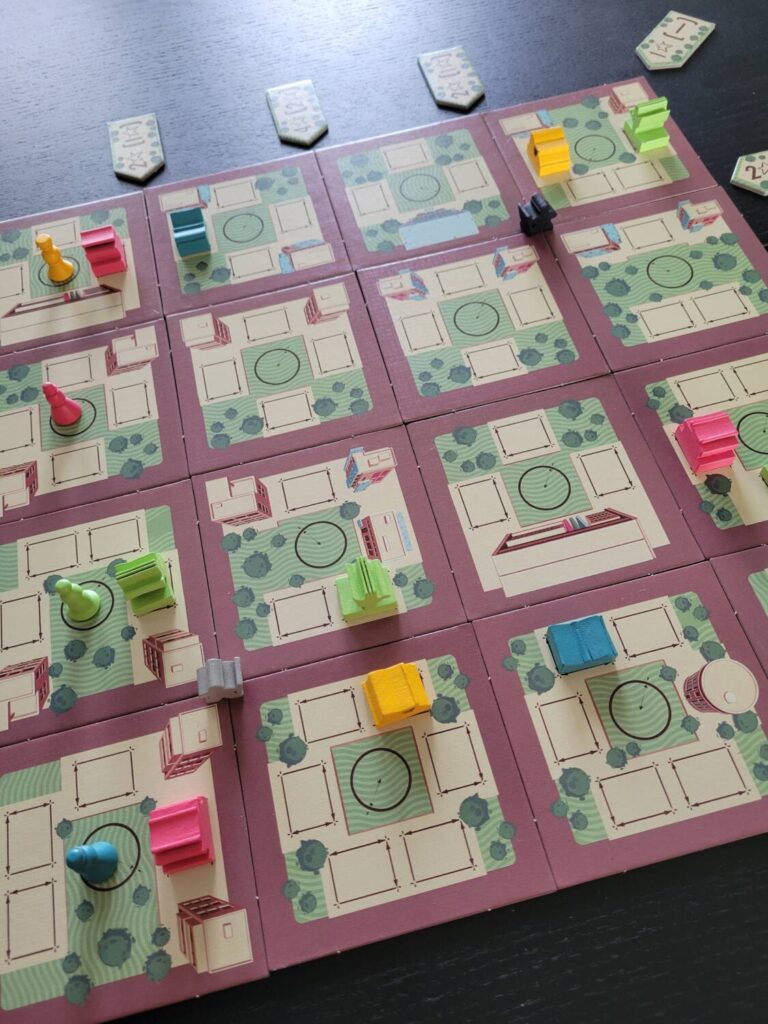

The game is mechanically elegant. On your turn, you move your little architect meeple around a 4×4 grid of a city, pooping out buildings along the way. You have a tableau of cards (a maximum of 3) that give you footstep icons, and each footstep lets you move to an adjacent intersection within the grid. You cannot stop on another player’s meeple, and for each step you take, you can plop out a building on one of the building plots that abuts the streets of the intersection. There are four colors of building: red, green, yellow, and blue, each represented by a lovely unique wooden piece.

You’re doing this running around and building to fulfill positional contracts. This leads into the other action you can take, which is adding another card to one end or the other of your tableau from a display of four available. When you add a card, it gives you more buildings into your personal supply—and, if the added card would be a fourth card, you score the card on the opposite end of your tableau.

The cards are contracts that score variable point multipliers based on relative positions of buildings and colors within the grid. You might see where I’m going here.

You scored me points!

Even though everyone’s available contracts and potential future contracts are on full display, and you could theoretically try to play counter to the contracts other players have at any given moment, two forces work against this. One, cards are repeated, and through bad flip luck and turn order, a player might get to capitalize on the same contract multiple times; two, the constrained grid makes it next to impossible to not accidentally help each other score.

This is something I see a lot, and struggle with myself in game design. There’s quite a bit to love in contracts that function this way, but it comes with an enormous problem to solve. That problem, if left alone, steals the feeling of playing well from players, which is the opposite of what you want in a game as thinky as this one. There’s a lot to like about the game, the color palette, the ability to rush the game by inefficiently accomplishing contracts, the special powers you can grab, and the small majority puzzle that is resolved at the end of the game—I haven’t really talked much about any of that.

The reason is that the contracts muscle out much of what is clever about the game, and you’re left with an experience that could be satisfying, were it not for the design running face-first into a classic problem. But, if you’re looking for a zippy 30-minute building game, there are worse games to pick from.