Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

And a 1, and a 2, and a 1-2-3

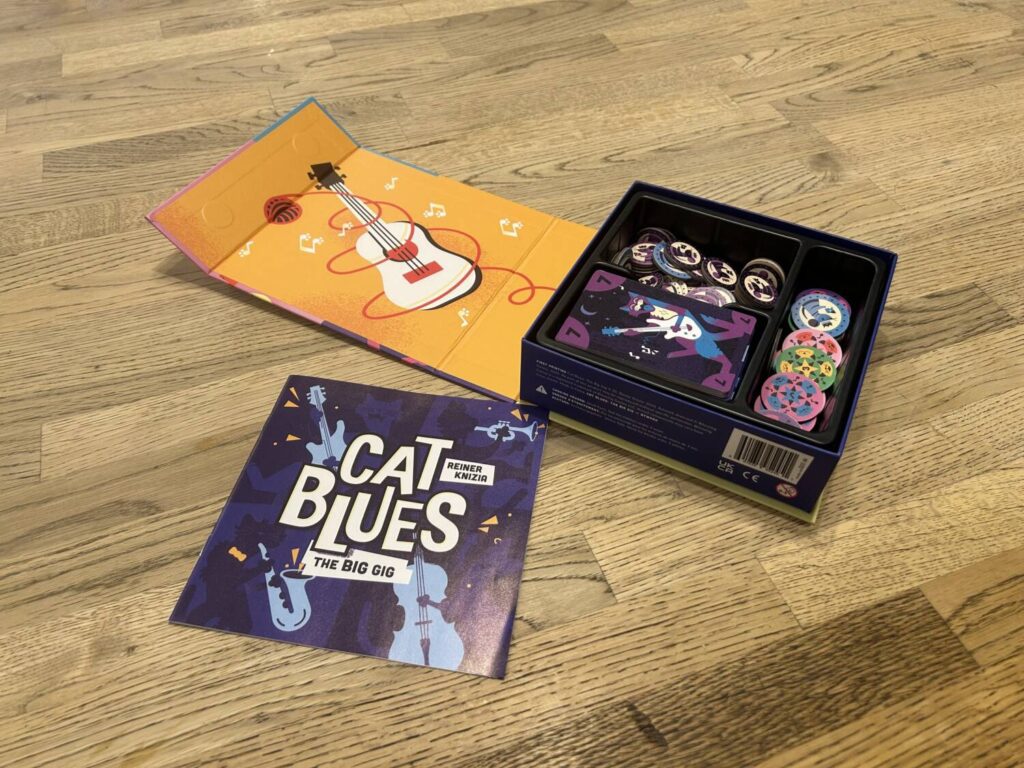

Cat Blues: The Big Gig is an auction game from designer Reiner Knizia and publisher Bitewing Games, a reimplementation of Knizia’s 1998 release Katzenjammer Blues. While the original has long been out of print—a 2019 Korean printing is the only edition from within the past decade—it has retained a minor cult following. With Bitewing’s appetite for reviving more obscure Knizia designs, a reprint felt inevitable.

What we have here is an auction game, played over three rounds. The deck consists of cards valued from 1-5, along with wild Jokers. Each auction starts with the Band Leader—the winner of the previous auction—revealing cards off the top of the deck until they draw either a duplicate of a card already in the market row or a Joker. At that point, the bidding begins, with the market row as the prize.

The player to the left of the Band Leader can make any bid they want. Bid values in Cat Blues are idiosyncratic, though sensible enough once you get the hang of it. You can either bid any number of cards with different values, or you can bid a specified number of cards of the same value. A bid with more cards always beats a bid with fewer cards, while a bid with a higher specified value always beats a bid with either a lower or no specified value. Two 3’s is better than a 5, three cards is better than two 3’s, and three 1’s is better than any of those.

Once every player save the last person to bid has passed, they discard the bid cards, pick up their winnings, and then have the option to meld sets. You score points in Cat Blues by collecting sets of four matching cards and playing them to the table in front of you. Each set scores you points equal to the value of the cards—a set of 4’s gets you four points, a set of 1’s gets you one—taken from a common pool of point chips. After you win an auction, you can meld as many sets from your hand as you want, but keep in mind that you’re also depriving yourself of cards to spend on future bids. Is it better to play those four 3’s or to hold on to them?

The Jokers can substitute for any card in either a bid or a melded set. While that’s a powerful tool, the player with the most Jokers at the end of the game, both on the table and in their hand, loses five points. That’s significant in a game like this. The only way to get rid of a Joker is to meld a set of four of ‘em, but it won’t score you any points, and card quantity is money in this game.

On top of all that, there are external timing considerations to keep an eye on. The round ends immediately if a player empties the common pool of points, or if the draw deck empties out. You can push your luck by holding out until later to meld, but you risk someone else ending the game. And remember, to meld anything, you have to win an auction, which means spending cards, and if your opponents recognize that you’re in desperate need of winning, they can make it cost you a whole lot.

Any one of these pressures is a great double-bind in and of itself. All of them together is excellent.

It’s the Cards You Don’t Bid

Cat Blues is typical of Knizia’s best work in that way, forcing players into the murky space between two potentially disastrous decisions, but we come now to a crucial difference between the Blues of a Cat and Katzenjammer variety: economy of scarcity. To the extent that Katzenjammer Blues is known for anything, it is known for being unforgiving to new players. An ingénue can overbid early in the game, meld a set, and find themselves consistently outbid for the rest of the game. If you don’t have any cards, you have no way of getting more, and you’re a passenger for the rest of this journey.

If that were the result of blind luck, I’d consider it bad game design, but you only find yourself in that situation if you did it to yourself. It’s a learning curve, one that’s alien to most contemporary audiences. Bitewing Games and Knizia have introduced a few modifications to soften the edges, including the option of drawing back up to four cards after winning an auction and completing any melds. While this makes Cat Blues more accommodating, and certainly lowers the age limit by a number of years, the change also drains most of the excitement from the game. There’s a huge difference between bids that are potentially punitive and bids that are nothing but gravy. I’ll take the punitive bids every time.

Other changes include the three-round structure and a set collection bonus. Players collect one Quartet Token for each card value melded across the three rounds, and the player(s) with the most score a massive bonus of ten points at the end of the game. This can create some fun interactions, as one player goes out of their way to deny another player the low-scoring value they’ve put off until the last minute.

Everybody Wants to Be a Cat

I would be remiss if I didn’t highlight the remarkable work of A. Giroux, the illustrator, who has cooked up all variety of musical cats for this deck. The decision to make the Jokers inebriated karaoke cats is immediately charming, and only becomes funnier when you consider that the player with the most off-key belters suffers a penalty.

Cat Blues: The Big Gig sits somewhere between a genuinely positive “fine” and “good.” I didn’t walk away from it with strong feelings, and nobody I played it with was gaga for it either. I think the changes Bitewing and Knizia have made, along with Giroux’s fabulous art, will find the game a larger audience, and for that I am grateful, but thank goodness they included Katzenjammer Blues in the box. That game is great.

I am not sure which I like better — the adorableness of a vicious game, or your prose, Mr. Lynch.

You are amazing.