Carcassonne has been winning people over for almost 20 years now, an incredible achievement in the tabletop hobby, especially with so many great new titles released each year. Today Meeple Mountain writers and Carcassonne addicts David McMillan and Andrew Holmes discuss just what it is that makes Carcassonne so great and keeps them coming back for more.

The game of Carcassonne begins with a simple mechanical framework that everything else is built upon. So before one can begin to dissect and discuss just what it is about this game that makes it so essential, it is critical to understand how it plays: click on the banner below for a brief overview if required. For those already familiar with Carcassonne’s rules, read on.

In the game of Carcassonne, each player is provided with 7 playing pieces (affectionately known to board gamers all over the world as ‘meeples’). Players are tasked with placing these meeples onto randomly drawn tiles in order to score points.

On a player’s turn, they draw a tile and then add it to the array of tiles that are forming in the center of the table. The tile being placed can be rotated in any direction so long as the placement of the tile follows these simple rules: roads must connect to roads, fields must connect to fields, and city pieces must connect to city pieces.

After placing the tile, the player can place one of their meeples onto one of the features of the tile so long as that feature doesn’t already contain another meeple (although a placed tile can connect separate features that each contain a meeple). Then any feature completed by the placement of the tile scores. Roads score 1 point for each tile that makes up the road. Cities score 2 points for each tile that makes up the city. Once completely surrounded by tiles, a monastery will score 1 point for itself plus a point for each surrounding tile – 9 points.

Fields score a bit differently than the other features and are only scored at the end of the game once the last tile has been placed. A field is made up of any tiles that share the same pasture land, unbroken by other features. Once the final tile has been placed the players count up the meeples in each field. If one opponent has more meeples in that field than any other, they score for that field alone. Otherwise the score is shared by the players with the most meeples there. Each field scores points for each completed city that borders that field. This can be worth a massive amount of points at the game’s end.

Meeples placed on completed roads, cities and monasteries are returned to their owners. The drawback of placing a meeple into a field, though, is that it’s stuck there for the entirety of the game. So it’s no big surprise that much of the game is usually spent either jockeying for sole possession of the choicest fields, trying to improve the scoring ability of specific fields, or enclosing fields as soon as possible to keep them from scoring even more points than they’re already going to.

As you might be able to tell from this rules explanation, Carcassonne is not without conflict. In fact, there’s quite a lot of it that may not be apparent on the surface. While you are never allowed to directly place one of your meeples onto a feature containing anyone else’s meeples (even your own) it is possible, through clever tile placement, to link together different tiles containing your meeples so that you have multiple meeples on the same feature. You can even use this tactic to join a feature that one of your opponents may have started. If that feature scores and you’ve got the same number of meeples on it as they do, you score the same amount of points. If you’ve got even more than they do, though, you get ALL the points. Understanding this concept and using it to your advantage is key to doing well at Carcassonne.

On Becoming a Tourist

Carcassonne was inspired by a visit to the south of France in the late 1990s where Klaus-Jürgen Wrede was researching the history of the Cathars. He fell in love with the landscape and wanted to create a game that imitated the growth and spreading of cities and castles.

David: While The Settlers of Catan was my first foray into the world of modern board gaming (and boy was I obsessed with that game), it wasn’t until I was introduced to Carcassonne that I fell in love. I can still clearly remember that night that my friends Lawrence and Lorraine invited me into their home and brought Carcassonne down off of the shelf. I was standing on a precipice that I wasn’t even aware of and I was about to take that final step off of the edge… and I was going to fall hard.

I think the first thing that surprised me about Carcassonne was how vastly different it was from Catan. I’m sure I was subconsciously aware that they were two different games, but I’d gotten so used to Catan at that point that Carcassonne came as a total shock to me. Where were the cards? Where were the resource bits? Why were there so many little tiles?

It wasn’t a very impressive looking game either. Essentially, all laid out, it’s a score track, a bunch of face down tiles in stacks, and some little wooden dudes gathered in front of you. It’s not exactly a game that would call you to the table if you saw it from across the room. So, as they set up the game for me that first time, I wasn’t very impressed. I was already wishing we were playing Catan instead. And then we started actually playing and that all changed.

Andrew: Carcassonne really doesn’t make a great first impression, does it? My wife and I had been invited round for dinner by a colleague from work and afterwards they suggested a game. They pulled out this uninteresting looking box and set about teaching us the rules, whilst I vaguely listened and mostly watched the silver cichlids flitting about in the tank behind them.

And then we started playing, and as the map grew between us I forgot the fish. In the first game I just enjoyed the activity but by the second game I was planning and scheming, trying to better my own position whilst simultaneously sabotaging everyone else’s.

We caught the bug there and then. In the car on the way home my wife searched online and discovered this interesting game was a thing and by the time we arrived home we’d agreed we had to have it for ourselves.

We introduced it to our friends, our families, really anyone we knew and spent countless hours laying roads, cities and acres of soft, comforting green. From this verdant spring-board we discovered the world of modern board-gaming.

On Becoming a Citizen

Klaus-Jürgen Wrede published Carcassonne in 2000 and in 2001, it won the Spiel des Jahres prize – the tabletop industry’s most esteemed award. Since publication Carcassonne’s rules have gone through two revisions, streamlining the first edition’s city scoring rules that scored fewer points if your city was made up of just two tiles and field scoring rules that were needlessly complex (not to mention outright confusing). Even now the field scoring rules are the hardest for new players to understand.

David: While Carcassonne can be played as a friendly game, I quickly realized you do much better by gunning straight for your opponents. I started my sabotaging right out of the gate. Having played Catan for so long turned me into a cutthroat and I brought that into Carcassonne. As we began laying out tiles and placing workers, I immediately began seeing opportunities to harass my opponents and cause them consternation.

I caught on right away to the subtle metagame that exists with the game itself. On the one hand, you’re drawing and laying tiles in order to score points. On the other, you’re playing a deeply psychological game wherein you’re trying to put pressure on your opponents to force them into a position of having to defend things and waste workers and scoring opportunities in the process. It’s a thin line to walk and I think that was ultimately the draw for me – that opportunity to be sneaky and underhanded and clever. From the get-go I was able to know when to press on and when to just let something go. I handily won that first game and I didn’t stop winning until I met my future wife.

Andrew: I think that’s what I especially like about Carcassonne. It’s playable with anyone but there’s a rare flexibility in how you play. In the right mood and with the right group I’ll play in exactly the same way as David describes: cutthroat and devious. I’ll try to tag onto other player’s cities and fields and share their hard-earned points. I’ll attempt to fence in early farmers (workers placed into fields) with roads if they look like they’re going to be too strong. I’ll even place pieces that make it hard for my opponents to complete features. But that’s only with the right people and atmosphere.

On other occasions Carcassonne can feel semi-cooperative, the group happily placing tiles to get an aesthetically pleasing effect whilst gently collecting points as they go along (and let’s not forget to mention the iconic art by Doris Matthäu – classy and classic). My wife and my brother regularly team up, manipulating the landscape to fit their devious plans of shared cities and amalgamated meadows until the rest of us are left behind and they can squabble like vultures over juiciest parts of the victory. And the process of building the map creates a feeling of togetherness no matter the play style on show and at the end the players can look down at a shared world they created together.

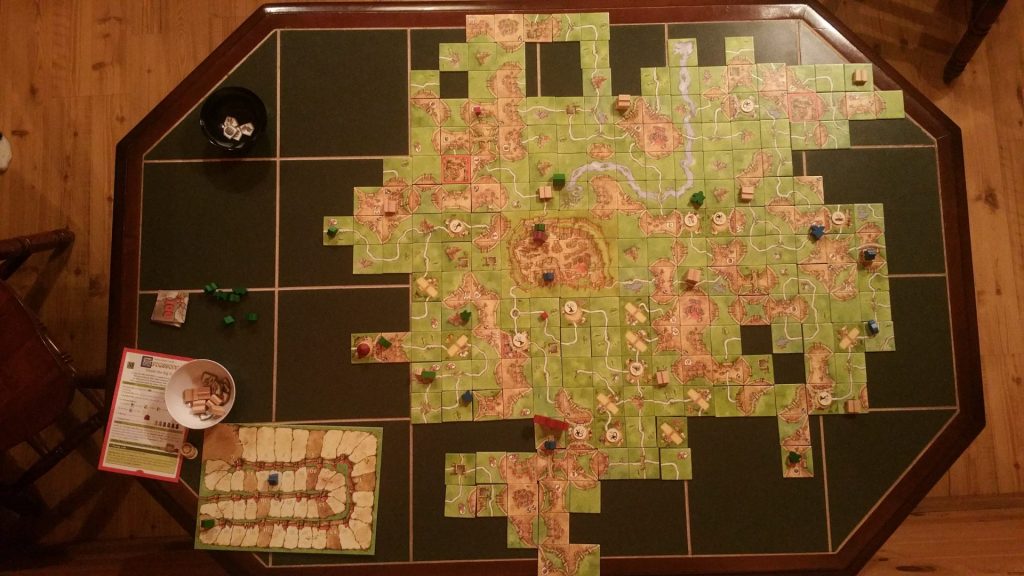

David: An almost boundless world limited only by the geography of your playing area!

Andrew: Exactly, adding expansions can make the game huge! Carcassonne can be cruel or generous, a quick fix or a whole evening. The game adapts to the mood of the players and feels different and interesting each time.

On Becoming a Defender

Nearly 15 years after it was first published ‘Carcassonne 2.0’ was released, featuring updated cover art, redesigned tile art and the new Abbot mini-expansion. Whilst the new tiles are compatible with the previous art, the contrast meant that some players felt this devalued Doris Matthäu’s artwork and betrayed the fans that had invested so much time and love into the earlier version.

David: I’ve seen a lot of people harping on Carcassonne because of the random nature of the tile draw, but it’s never seemed like that mattered all that much to me. Sure, you can never be certain exactly which tile you’re going to draw next, but after you’ve played a few times you start to have a good feel for how many of each tile are in the game. Then you can start making educated plays based on the likelihood of which tiles are going to be coming out in future turns. There’s a bit of risk versus reward in Carcassonne and it’s delicious. There’s always a temptation to try to sneak onto someone else’s property or to get a big city going, but should you? How likely are you to draw the tile you’ll need to connect everything together? And when you start talking about farmers, then you’re really getting into risky territory. I think it remiss of a person to focus solely on the random nature of the tile draw because Carcassonne is all about taking that bit of randomness and figuring out how to use it strategically. I really like that.

Andrew: The luck of the tile draw is what makes the game interesting. You can mitigate this to an extent by letting players hold 1 or 2 tiles in their hand at all times so that they have some choice but for me that changes the decision space of the game, and not for the better. Carcassonne works as it is because the risks and rewards change over the course of the game. Towards the start you can be confident that you’ll get the tiles you need to complete that huge city you’re building. But as the game progresses your chances of getting the tiles you need decrease so the risks are higher. Giving players a choice of tiles dampens the scale of this arc, and increases the amount of time spent analysing your move, slowing the game down and killing what makes it such a joy to play – its lightness.

David: There have been some pretty heated debates at Meeple Mountain about the “hold two tiles” house rule. Thank you for summing up everything that’s wrong about that approach! I feel somewhat vindicated now.

Andrew: That balance of luck and skill is also why Carcassonne is the quintessential ‘gateway game’. Carcassonne’s gameplay of emerald fields and topaz cities has an elegance that many other games simply lack, an alchemy that turns ordinary card stock into gold. Good players will always beat poor players but luck tempers any resentment. The rules are straightforward, the game play is tight, fast-paced and inherently satisfying, and the mechanism of making the board (map) as you play is intriguing compared to the previous board gaming experiences of most new players. Carcassonne acts as an enabler, a friend who provides that first innocent fix and gently ushers us unknowingly towards full-blown gaming addiction. Carcassonne’s rabbit hole leads to the rest of modern board games but also to one of the most extensive and successful series of expansions in the history of board games.

On Becoming a Builder

Carcassonne is one of the most prolifically expanded board games in the entire hobby. Board Game Geek currently (as of September 2019) lists Carcassonne as having 94 expansions, 89 versions, 6 video game adaptations and 16 spin-offs. Editor’s Note: As an example of the continued growth of Carcassonne, in the few weeks between drafting this article and its publication the game has added listings on Board Game Geek for 1 additional expansion and 2 more versions.

David: I’m glad you mentioned expansions. That’s always been one thing about Carcassonne that has really impressed me: even the tiniest expansion can change the game in really big ways.

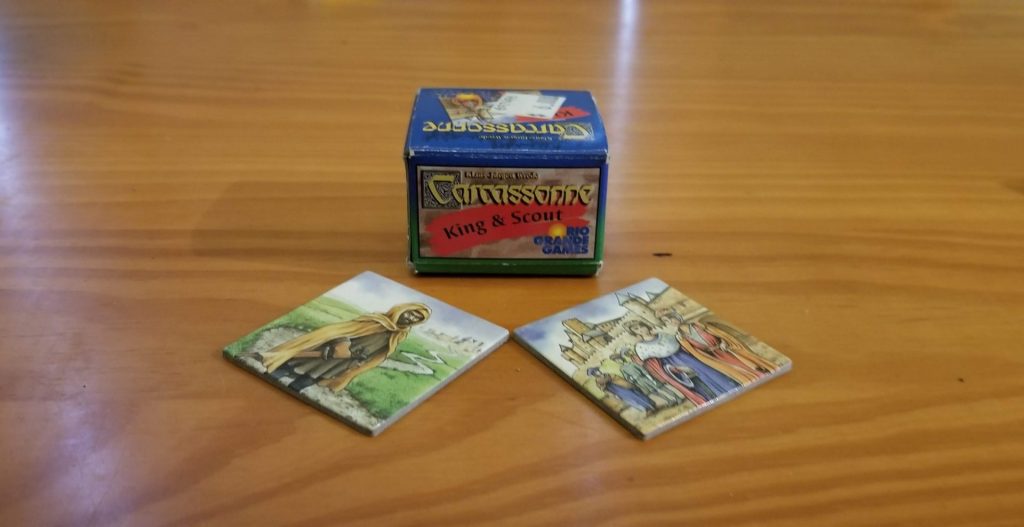

I have been playing Carcassonne for quite some time now. Back when Carcassonne was still in its infancy, many of the expansions we see today (such as Count, King and Robber) were originally released as mini-expansions that came in their own tiny little boxes. One such expansion, King and Scout, introduced two game changing tiles to the game, the nominal King and Scout. The King tile is awarded to whomever completes the first city. If someone else completes a larger city later on, the King goes to them. At the end of the game, whoever holds the King tile scores 1 point for every completed city on the board. The Scout works the same way, just for roads instead.

Notice I said that the bonuses are awarded when features are completed. This creates an impetus to complete features that you might not even score any points for just so that you can steal the King or Scout from someone else. Suddenly, everyone’s focus shifts from building these massive 30 point cities to building cities just large enough to take the King tile away from their opponent. Meanwhile, everyone’s cranking out tiny little 4 point cities all over the place. This has the net effect of also making fields far more valuable than they ever were in the base game.

Andrew: Seriously, an addition of two tiles and Boom! a very different game!

David: It’s really neat to see how each of the expansions melds into the game effortlessly while causing massive upheavals at the same time. The King and Scout expansion also included some bonus tiles for one of the Carcassonne spin-off games, Carcassonne: Hunters and Gatherers. That’s another really impressive thing about the Carcassonne system – it’s inspired a whole bunch of spin-off games and while they all feel very distinctly Carcassonne, they all play very differently.

Andrew: It’s hard to think of another game that has consistently released so many strong expansions. In particular, the first run of four (Inns & Cathedrals, Traders & Builders, The Princess & the Dragon, and The Tower) feels like a streak of creative success that’s unrivalled in the industry.

I like the way expansions often highlight a particular playing style. There’s the push-your-luck of Hills & Sheep, a focus on adjacency in Under the Big Top or the increased importance of roads and the introduction of auctions in Bridges, Castles and Bazaars. And yet all the while it rewards clever play and thoughtful manoeuvring.

Kurt Refling, interrupting: My personal favourite Carcassonne expansion is The Catapult, it’s the perfect expansion and I’d stake my board gaming reputation on that statement. It just feels like when Carcassonne became the game it was always meant to be, you know?

Andrew: Thanks for that Kurt, nice of you to drop by. The Catapult is critically reviled but I have to admit that passing up the opportunity to buy a copy of it at a decent price is my only tabletop regret. It goes for serious amounts now.

Klaus-Jürgen Wrede has said that The Princess & The Dragon is his favourite expansion, and I think I agree. When the dragon is triggered the players take turns moving it, with any meeple in its path eaten (returned to their owners). Clever manipulation can result in interesting dilemmas: my brother’s fiancée once had two possible places to move the dragon, each tile containing a different player’s meeple. She deliberated for a while but as soon as someone pointed out that her choice was between her fiancé and her future mother-in-law the decision was made. Needless to say, my brother let out a cry of outrage as his piece was removed from the board but the rest of the table was howling with laughter.

David: My wife and I collectively refer to The Princess and the Dragon, The Tower, and The Count of Carcassonne expansions as “divorce expansions”. While the interactions in the base game and the other expansions are subtly aggressive, there’s nothing subtle about the aggression in these three.

Andrew: Such a good name for them! Combining both The Tower and The Princess & The Dragon makes Carcassonne the harshest and most cunning game I have ever experienced. I’ve never added The Count as well, that could be… interesting!

On Becoming an Envoy

Carcassonne’s impact spreads far beyond serving as the inspiration for tile-laying games like Isle of Skye or Lanterns. Carcassonne introduced the world to the ‘meeple’ designed by Bernd Brunnhofer, a person-shaped playing piece that quickly became a symbol of modern tabletop gaming. The word ‘meeple’, a portmanteau word for ‘my people’, is never mentioned in the rules (they’re ‘followers’) and is thought to have been coined by a Carcassonne player. Naming origins aside, the meeple is now a component in thousands of board games, has spawned an entire industry of custom and deluxe components, as well as being half of this website’s name. Without Carcassonne Meeple Mountain could have ended up as Cube Crag or Pawn Peak…

Andrew: In our family we had the ‘Christmas of Carcassonne’, the year when we gave my brother and his fiancée a big box version whilst they in turn gave us a custom wooden storage box. Our tiles now stand in ordered rows waiting for exploration like the pages of a stately atlas. To open this splendid box of potential is to unleash the evocative scent of wood and cardboard and to anticipate embarking on a fresh journey of discovery and creation. And then, as you start to play, a carpet of resplendent countryside creeps across the table as if captured via time-lapse photography.

I am fond of Carcassonne because it was our first true encounter with modern board games. I like it because it’s quick and clever, it tells stories of great success and comic failure, and because it’s never given me a dull game. But mostly I love Carcassonne because it brings people together in a way that more complex games are too taxing for and more party-style games prevent by their very mechanics. It hits a sweet spot between competition and socialising and it does it softly, with a twinkle in its eye. For me that means more than anything. We catch up with one another whilst the world of Carcassonne spreads before us, each pixel-tile adding to the whole to form a gloriously bucolic vista between us, landscape pointillism in game form.

David: Regardless of what kind of gamer you are, Carcassonne’s got you covered. That’s what keeps me coming back. I can really appreciate the elegant design underlying everything and I really love the way that just adding a few extra tiles changes the way that you approach the game. In fact, the only other game I have ever played that has given me that same feeling is Magic: the Gathering and the fact that I am comparing Carcassonne to that most sacred of games should tell you something. Carcassonne’s a game that belongs in any gamer’s collection. There’s something there for everyone, new players and seasoned veterans alike.

Carcassonne is widely recognised as being one of the quadrumvirate of gateway board games, along with Catan, Ticket to Ride and Dominion. Since its publication Carcassonne and its various expansions have sold over 10 million copies and been translated into more than 27 languages, making it one of the most successful board games of all time. Want to know more about this board game behemoth? Check out Meeple Mountain’s epic History and Celebration of 21 Years of Carcassonne. Alternatively, you can read our Carcassonne Android App review, our Carcassonne Strategy Guide, or even Meeple Mountain’s Carcassonne Haiku.

Kurt: Aw, come on guys, I was just joking about The Catapult. I can’t believe you’re going to leave it in the article…David..? Andrew..? Guys..? Oh dang!

Thank you for review this game. It may be an oldie, but oh boy is it a goodie! This was my “gateway” game years ago and it’s still my all time favorite game today.

I’m glad you enjoyed our review. It’s always a pleasure to meet another Carcassonne fan!

Is it legal to place a city piece and meepal on a cap that you cannot finish… Ie the city has 3 closed sides, you cap the top but don’t close it, the only play left is the city center or the 4 sided complete tile… can you join that city?

The way I interpret your question is that you have three unconnected city sections that just need a piece to be placed at the intersection where they meet in order to connect them, and you’re wondering if it’s allowable to place a fourth unconnected city space above that intersection. If that’s your question, the answer is “yes”. Until those sections are connected, they are considered to be parts of 3 to 4 seperate cities. Only when they are connected do they become a single, unified city.

Also, thank you for taking the time to read our piece and comment on it. We really appreciate it. =)