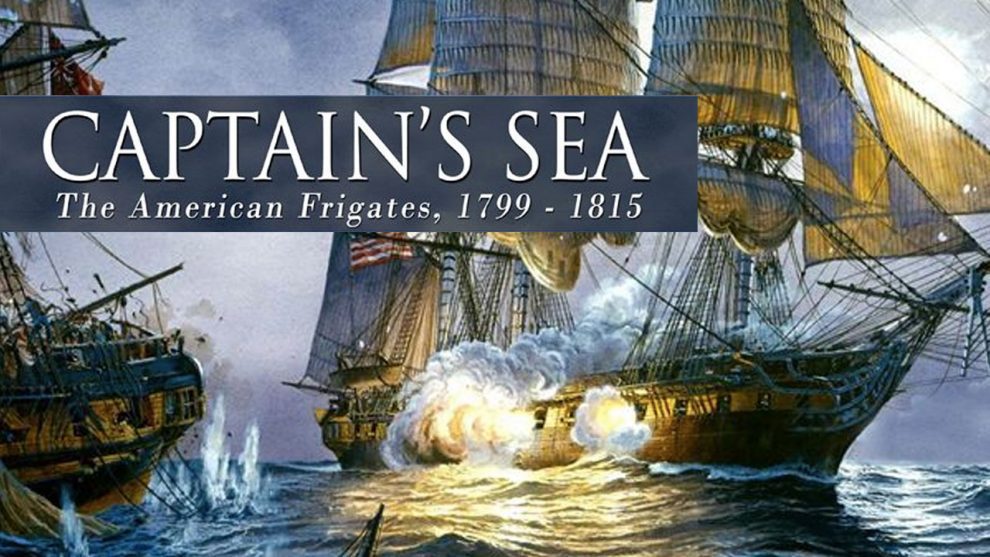

Captain’s Sea pits the frigates of the US Navy against those of Great Britain and France from 1799 to 1815. During this period, the US Navy was in its infancy, having only been formed by Congress in 1798. Prior to then, the only naval action the United States experienced was during the American Revolution, and most of those engagements took place on rivers, lakes, and along the coast of the Eastern seaboard. By the early 19th century, the US began to develop a truly ocean-going navy capable of fighting it out on the high seas against their much more experienced European rivals.

Released by Legion Wargames late in 2021, Captain’s Sea is like many games by this publisher who specializes in smaller wargames. Founded in 1990, Legion Wargames’ goal is “to bring you a fine selection of military board games which cover topics that are as of yet un-gamed, or new game systems that offer a unique perspective on history.” Their titles include games about the Boer Wars, Spanish-American War, Indian Wars of the American West, and the New Zealand Land Wars. In a hobby dominated by games about the World Wars, Napoleonic battles, and the US Civil war, Legion Wargames provides unique games and a chance to learn about these lesser-known conflicts.

I’m a big fan of the Horatio Hornblower series – both the novels and television series – and the movie Master and Commander. So, when Legion Wargames announced they were releasing a game of ship-to-ship combat in the age of sail, I had to give it a try. Another reason Captain’s Sea caught my interest was its scope: single ship versus ship combat. It was designed by Mike Nagel, whose credits include the Flying Colors series of naval combat games also set in the age of sail. By contrast, Flying Colors involves fleet battles with dozens of ships on each side. As such, its rules are more complex, and the game takes longer to play than Captain’s Sea. Don’t get me wrong. I enjoy Flying Colors. But I simply don’t get it to the table as often. The single ship versus ship combat in Captain’s Sea makes for a much more approachable game that can easily be played in a single session.

The Weather Gauge

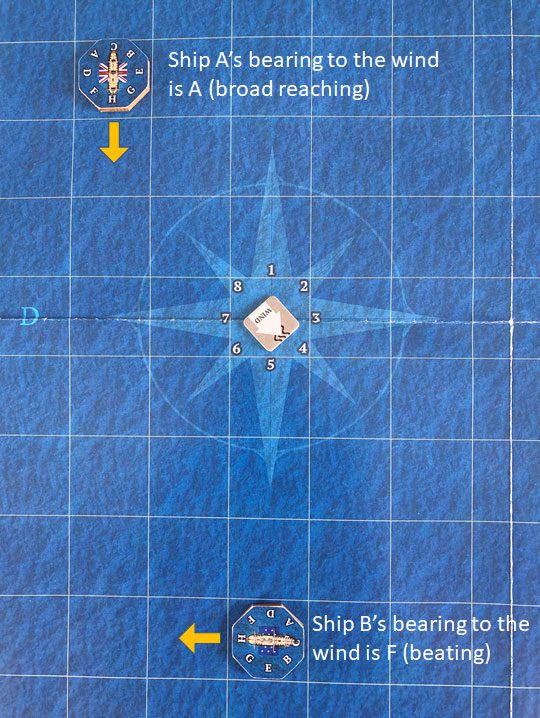

The main concept Mike Nagel designed Captain’s Sea around was the “weather gauge.” As he states in his designer notes: In its simplest terms, the “weather gauge” is a measure by which a ship controls a battle through maintaining a superior position relative to the wind. For example, Ship A is upwind of Ship B (see illustration). Because it has the wind at its back, it can move faster and decide when to close the distance with Ship B. That’s because Ship B must “beat” into the wind, tacking left and right, for it to close the distance with Ship A. So not only is Ship B going slower because it is moving upwind, but it must cover a longer distance. That makes it easier for Ship A to evade Ship B simply by “wearing away”, thus maintaining the distance between the two ships until they’re ready to close (for example, after they’ve reloaded all their guns). While Ship B can also turn so the wind is at its back, Ship A can maneuver their ship to get directly upwind of Ship B and steal some of that wind, thus giving it a speed advantage. If you ever watch an America’s Cup yacht race, you will see this tactic used often to overtake another yacht.

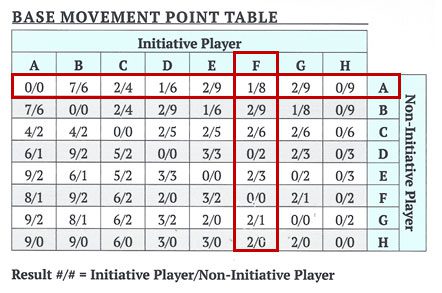

The way this works in Captain’s Sea is that at the start of each turn both players roll a die to determine who has the initiative. The players cross reference their bearing to the wind in the Base Movement Table to determine how fast their ship is sailing relative to each other. The first number left of the slash is the speed of the initiative player’s ship, and the second is that of the non-initiative player. Thus, if both ships are moving in the same direction relative to the wind, then their base relative speed is zero. However, these base speeds can be modified by the ship’s hull type and by the ship’s crew quality.

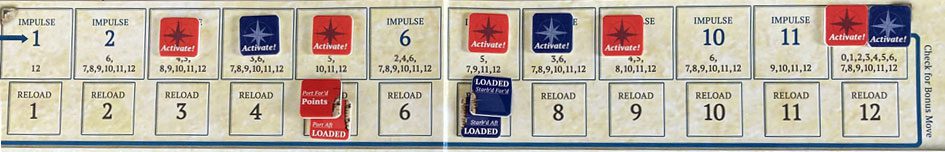

The final speed determines how many Activate markers can be placed on the Impulse track and on which specific impulses. For example, suppose the British Frigate had a final speed of 5, and the American frigate had a speed of 3. They would then place their Activate markers (red for the British and blue for the Americans) as shown here on the top row. Note that the impulse track is also used to keep track of how many impulses it takes to reload guns that have fired. In this example, the British not only get more activations, but their guns will be reloaded before the Americans.

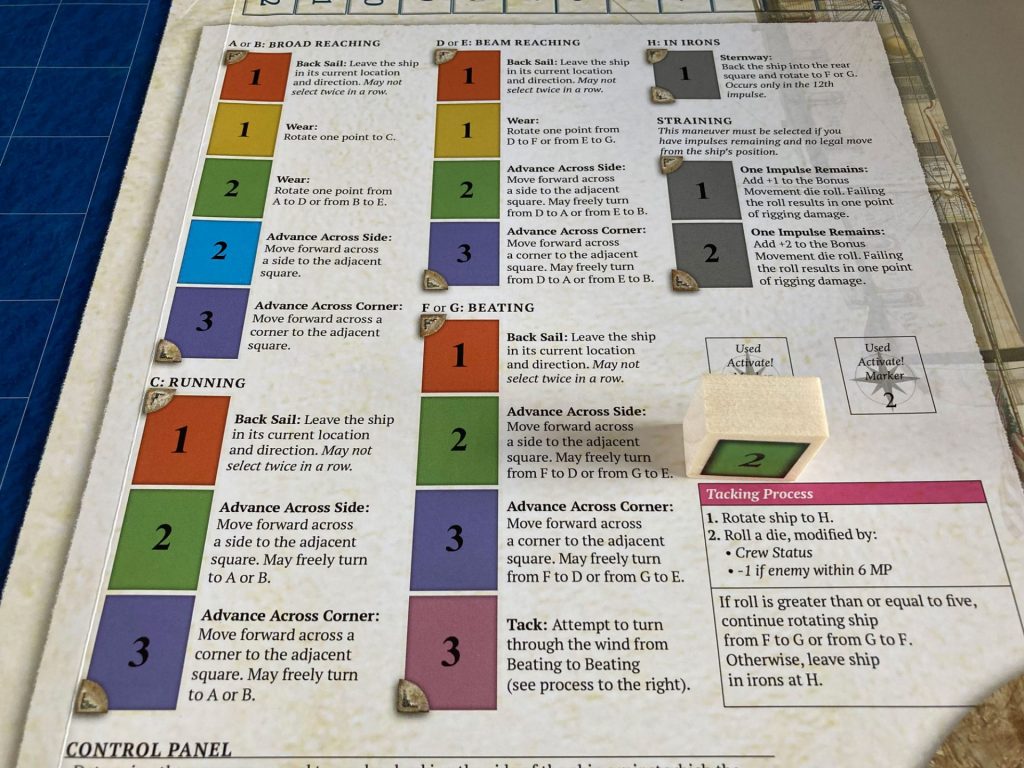

Players then secretly select a maneuver from the Control Panel by standing up a maneuver block. The side facing them shows the maneuver, while the side facing the opponent shows only their flag. The selected maneuver must conform to the ship’s current bearing relative to the wind and heading. From our earlier example, Ship B is facing a side and beating into the wind. Therefore, it cannot select the Advance Across a Corner maneuver. Its only choices are to Back Sail, Tack, or Advance Across a Side. In this example, the captain selected to Advance Across a Side. The number shown by the selected maneuver block equals the number of activations that must occur on the impulse track before the ship can perform the selected maneuver. Therefore, a ship with more activations will be able to perform more maneuvers during a turn. This maneuvering advantage is how the game simulates having the weather gauge.

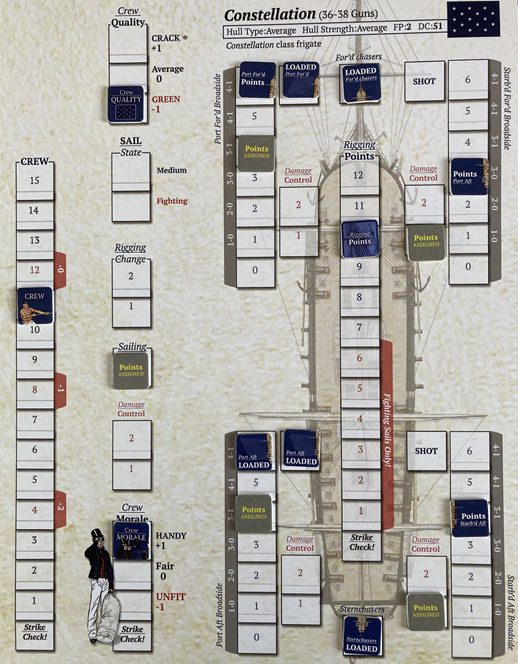

The Importance of Crew

The other main design concept is the crew. Each turn the player must assign their available crew to man the guns, go aloft to work the sails, perform damage control duties to repair parts of the ship, etc. There is not enough crew aboard a ship to man every station. Thus you, as the captain, must decide how to best allocate your available crew to fight the ship. Do you man your port or starboard gun batteries? Do you have some crew ready to repair damage? Do you have them aloft to help with maneuvering the ship? These are some of the difficult decisions players will have to make.

As hits are scored on a ship, some of those hits will result in crew casualties, making it more difficult to fight the ship. Each crew starts the game with high morale, but this erodes as they take casualties, and the ship suffers damage. This is reflected in lower die roll modifiers when taking certain actions. Additionally, not all crews are alike. There are three different crew quality levels: crack, average, and green. The more experienced the crew, the better their die roll modifiers and the more rapidly they can reload their guns. If a ship takes enough crew casualties, hull hits, or rigging damage, it will have to roll a die to determine if it decides to strike its colors and surrender.

Round, Double or Chain Shot?

Another decision the captain must make is what type of shot to use in ship’s guns. Each ship has a forward and aft gun section on the port and starboard side (left and right, respectively, for you landlubbers) of the ship. Each can be loaded with one of three different types of shot. Round shot is a single round cannon ball and is most effective against an enemy’s hull to take out their guns and hole the ship so it takes on water. Double shot is the practice of loading two cannonballs in each gun. While potentially more devastating than a single round shot, there’s a greater chance of the barrel exploding. Chain shot – two cannon balls connected by a length of chain – is most effective against rigging and is used to impede the enemy ship’s maneuverability.

When firing during an impulse, captains must then decide if they’re going to fire low against the hull or high against the rigging. Obviously, it helps if you have the correct type of shot loaded in your guns when you do. Furthermore, each gun section comes equipped with standard long-range cannons, and a smaller number of carronades. These shorter smoothbore cannons were more destructive at shorter range, giving each captain yet another choice in the game. As captain, you’ll have to decide which guns to use; a smaller number of potentially more damaging carronades or a greater number of long guns that could result in more hits.

Each frigate also has a single bow and stern chaser gun for use when they are headed directly towards the enemy or running away. However, be very careful about presenting your bow or stern to your enemy. This could result in raking fire – cannon fire directed parallel to the long axis of your ship. This can result in more damage and crew casualties because the cannon balls pass through more of the ship.

Game Components

The game’s components, while not fancy, are perfectly functional. The board is a paper map sheet of the ocean with a square grid superimposed. The center of the map contains the wind gauge. The setup instructions for each scenario indicate how to place the Wind counter to show which direction it is blowing. The map sheet also contains the Impulse Track and two Control Panels, one for each player on opposite sides of the map. The ships are represented by octagonal counters. The maneuver blocks are wooden, while the rest of the pieces are half-inch cardboard counters.

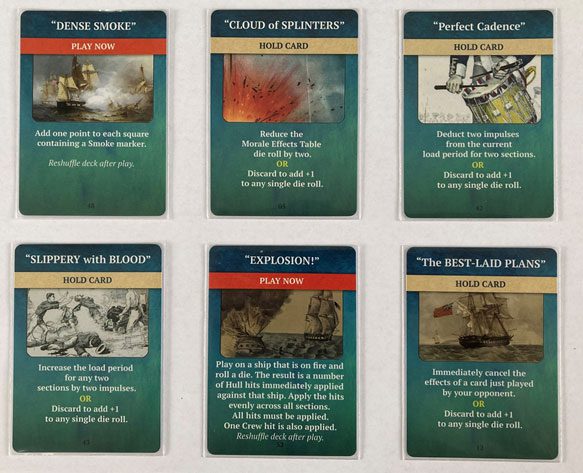

The game also comes with a deck of Bridge cards that represent random events. There are two types of cards: Hold and Play Now. As the names imply, you can keep Hold cards in your hand and play them when you wish, while Play Now cards must be played immediately upon drawing them. Each player also gets a two-sided player aid sheet with an abbreviated sequence of play and all the different tables used in the game. There are eight double-sided ship mats representing the different frigates in the game, as well as six dice.

The 16-page illustrated rulebook is written in large font and is quite clear. The rules are easy to understand, although there were some errors in this first printing. Thankfully, Legion Wargames provides an errata sheet with the game that contains rules clarifications and corrections to both the rulebook and player aids. The 24-page playbook contains an extended example of play, designer notes, and the scenarios. The rulebook also includes information that will allow players to design their own scenarios.

Impressions

Captain’s Sea successfully captures many aspects of naval combat during this era: the importance of having the weather gauge, the quality and morale of your crew, and deciding when and how to close with the enemy to deliver a broadside. The game offers lots of decisions. Where do I place my crew? What kind of shot do I load in my cannons? What maneuver should I select? Choose unwisely and you can be in for a rough time.

For example, in my first game I attempted to tack into the wind to get in a position to rake my opponent. But the maneuver failed, causing my ship to be “stuck in irons” (facing directly into the wind). When this happens, your ship loses all headway, is pushed back one square, and can’t perform any maneuvers for the rest of the turn. I was a sitting duck and paid dearly for trying to surprise my enemy. Fortunately, I was able to get upwind of my opponent and beat (no pun intended) a hasty retreat before being forced to strike my colors.

While there is a lot of die rolling in the game, they are resolved quickly, especially when you get accustomed to the die roll modifiers. The pace never seems to slow down and keeps you engaged even when your opponent is taking an action because you need to pay attention to what your opponent is doing. The ship mats are visible and open to inspection to both players, so you can see where the crew has been stationed. If all the port gun sections are manned, then you may want to try and maneuver to the enemy’s starboard. Likewise, since the number of available maneuvers based on a ship’s bearing to the wind is limited, you may be able to deduce what your opponent is going to do.

There’s a great cat-and-mouse feeling to this game. The ship with the weather gauge is the cat, and the other is the mouse. But these roles can reverse quickly. You really feel like you’re matching wits against your opponent. And because it’s single ship versus ship combat, misjudging your opponent’s intentions – or pushing your own luck with an aggressive maneuver – can be more costly than if you were battling fleets of ships. It’s what makes this game stand out against other naval warfare games.

The only criticism I’ve seen regards the game’s relative speed system. As one poster on BoardGameGeek noted, if both ships are on parallel courses, their base speed is zero. That means neither ship receives any impulse activations to move or change heading that turn. The only activations would come from their hull type and crew quality, and usually those are very low. It’s a fair point but didn’t diminish my enjoyment of the game.

Summary

Captain’s Sea is a terrific game. It offers lots of decisions in a fast-paced, action filled package. I didn’t even get close to describing all the finer details this game has to offer, such as the effects of the smoke produced when you fire your guns, the possibility of fires, and “straining” maneuvers. Yet none of these details bog the game down like the “chrome” in other wargames. Furthermore, the game is easy to learn, and a heck of a lot of fun. If you’re at all interested in naval combat in the age of sail, give Captain’s Sea a try.

Add Comment