When the mere mention of the franchise name causes twelve to fifteen thousand people to open their wallets in support, I suppose the world should take notice.

Canvas, from Road to Infamy Games (R2i) is the design of Jeff Chin and Andrew Nerger. And while the game itself presents its own merits, the artwork of Luan Huynh is perhaps deserving of the greater accolades. Canvas is one of those games that is so very visually satisfying that the game itself often fades into the background.

But there is a game inside this beautiful box. In fact, there are now three games inside three beautiful boxes rounding out this trilogy franchise thanks to three ultra-successful Kickstarter campaigns. Today we’re looking at the base box that started it all.

Shape

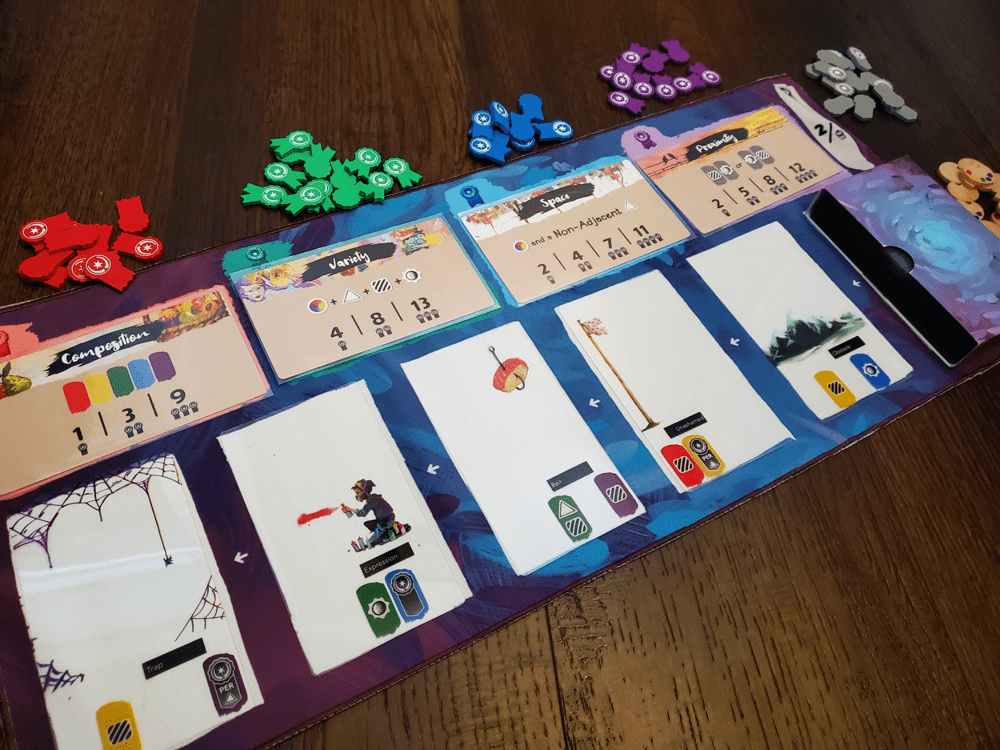

The hook in Canvas is the transparent cards that eventually comprise the various player paintings. These cards are revealed in a five card market that slides along as cards are claimed. The cards are stored in a box so as to prevent sneak peeks.

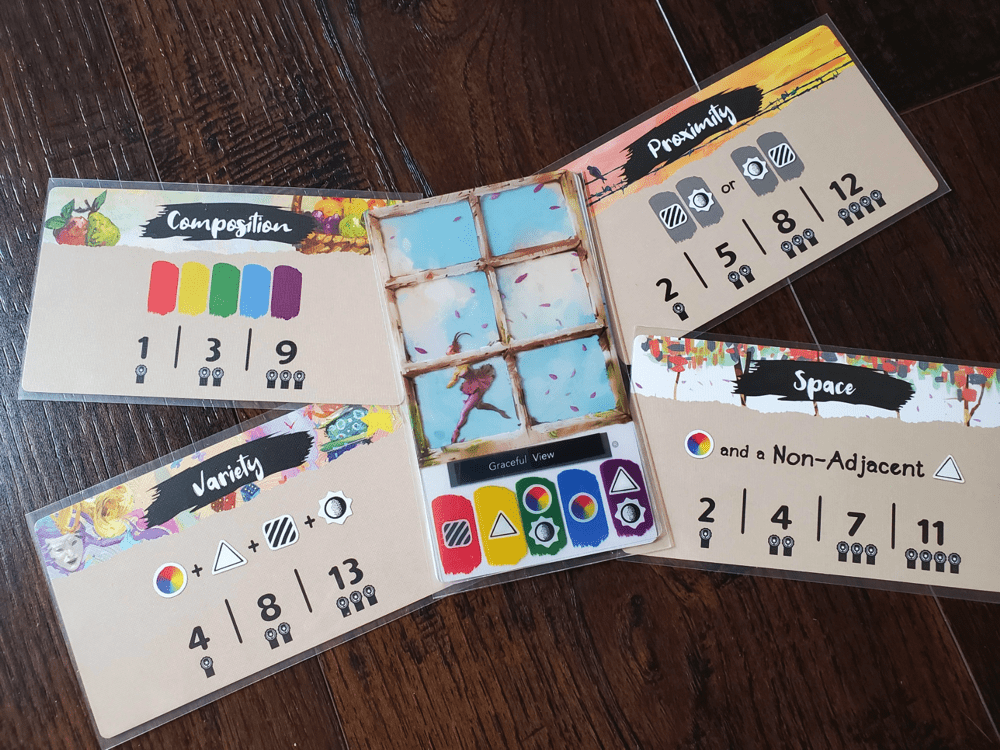

At the outset, four cards are chosen as artistic goals for the game. The back of the rulebook contains a number of suggested combinations that correspond to skill levels and thematic presentations, but randomness is always an option. The goals drive the choices as they harvest the symbols on each of the transparent cards for scoring purposes.

Each player turn consists of either visiting the market to claim a card or presenting a finished painting. When visiting the market, the first card is free, but skipping cards requires a deposit of one imagination token for each card. These collected imagination tokens remain on the cards until they are claimed in a later turn.

Presenting a painting requires three cards from the possible hand of five. Should a player ever reach five cards, they must present on their next turn. The three cards are (hopefully) stacked in such a way as to maximize the scoring potential of the various symbols in accord with the goals. Of course, as each painting will be stunning in its own right and will also boast a fascinating name, much fanfare is required in order that each work be celebrated for its creativity and ingenuity. Or not.

As each player will present three paintings, the final score is determined by the number of times each of the goals is accomplished during the game. The worth of the accumulated ribbon tokens determines the winner.

Texture

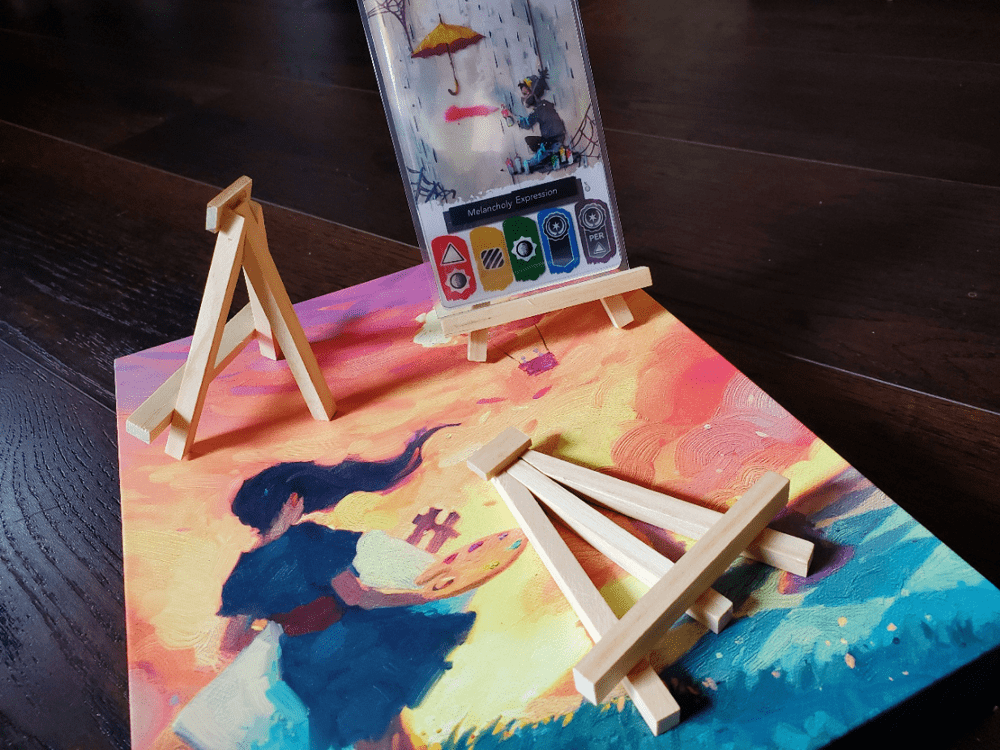

The cards are quite a lovely production. Each comes with a protective film that will show its corners over the course of a few games for removal. Slightly annoying, yes. But the clarity of the cards is a delight. The titular words below add a bit of flavor.

The original Kickstarter production had a simple canvas mat rather than a board for the goal cards and the market. I rather like the simplicity of the production. Depending on the version, the ribbons are either wooden or cardboard. Honestly, I don’t mind either avenue. Even the cardboard bits are sturdy and two-sided to sustain the curb appeal.

Each set of transparent cards is presented over a base card in a sleeve—and on an easel. The easels are of the dollar Walmart variety, but when they stand properly (let the reader understand) they really do help the production to pop.

The game box is meant for more grandeur than the typical KALLAX can provide. With nary a printed word to be found, the box is made to hang on the wall. I love board games, but I’m not the type of guy who puts holes in his wall for such things. Because if I’m looking at it honestly, it would take a screw to hold the weight of the contents. Still, I admire such dedication to the thematic content of the experience. I imagine pulling the game down from the wall for a game night with friends is a unique thrill.

Hue

Canvas is strange because, in a sense, I’ve already encapsulated the entire experience. The teach takes a few minutes. The whole game could be over in less than a half-hour. And yet, there is more to this little work than meets the eye, provided you have an interest in the window dressing.

From an aesthetic standpoint, I cannot describe the effect of the artwork, exactly. It matters. I’ve watched players almost entirely eschew the goals in favor of producing eclectic goodness only to explore afterwards whether it was worth anything on the scoreboard. I’ve watched players who unmistakably care about the scoring bend their intentions by a ribbon or two to make the painting more interesting. I’ve also watched players virtually ignore the artwork until it came time to present, only to then seem disappointed that they hadn’t made something more pleasing to the eye. Nowhere in the rulebook is there a sanction about goodness, beauty, or even entertainment, but the unspoken rule is that it’s not irrelevant. It almost seems an injustice when ribbons shower upon a miscreant showpiece.

Tone

Canvas is pretty good. Foundationally, it is an abstract game of collecting and organizing symbols to satisfy a set of arbitrary objectives. Superficially, however, it is just beguiling enough to elevate itself above its foundational limits.

The puzzle here is, at times, agonizing. The economy, revolving around the management of a limited and revolving supply of imagination tokens, is tight enough to be painful. In surveying the market, your imagination will repeatedly write checks your brain can’t cash. Therein lies the real challenge of the game: will you manage the market well enough to have what you need when you need it? And will it still be pretty?

Strategically, I have found it beneficial to be working on roughly one-and-a-half paintings at a time. The management of imagination tokens will often mean taking a suboptimal card in the name of “thinking ahead” while biding time for the card that will complete a masterpiece. Of course, by the third painting I’ve occasionally thought so far ahead that I’m apparently playing the next game, because the cards I have collected are utterly useless. I guess I appreciate the mental gymnastics.

Success in Canvas is rather satisfying. Recognizing the usefulness of a perfect card and properly risking its availability at the right time strikes a sweet spot in my sense of enjoyment. Likewise, pulling together a really charming artistic piece that actually scores well is super fun. Moments like these keep me coming back.

In one of my favorite holiday movies of recent years, The Man Who Invented Christmas, the elder Mr. John Dickens repeatedly says, “People will believe anything if you are properly dressed.” With a cold intellect, it would be terribly easy to look at the production of Canvas as little more than an exercise in excess. Sure, the transparent cards need to exist for the overlap of the symbols, but 80% of each card is useless from a mechanical and practical standpoint. But somehow, the dressing is just right for folks to believe it worthwhile. Canvas sells itself with gusto.

I can’t place Canvas among my absolute favorite games, but I’ve held onto it for the unique blend of simple mechanics, novel components, and aesthetic charm. I dove into the first expansion, Reflections, but I didn’t back the second, Finishing Touches. The excess isn’t as appealing to me the third time around, though I’m sure I’ll get it played eventually.

But the original has held just enough of its initial draw to come back to the table every now and again. It turns out there is a dandy of a puzzle hanging out on that bottom 20%.

Add Comment