Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Title: Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design: An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms

Authors: Geoffrey Engelstein & Isaac Shalev

Illustrator: Daniel Solis

When I still worked full-time as a board game teacher, there were a few games we used to play. I’m not talking about games we played on purpose, like Catan or Ticket to Ride. No, the games I’m talking about were a natural product of our job. One of these games was called I Found a Piece on the Floor and Must Now Figure Out What Game It’s From. Another was called Organizing These Box Contents in a Way Our Customers Will Actually Carry Forward. But the most common game, in my experience, was this one: What is the Half-Remembered Game This Person is Describing?

Here’s an example of what that game looked like.

Teacher: Do you folks need any recommendations?

Customer: That would be awesome, actually.

T: Cool! So I can understand your tastes a little bit, what are some games you’ve played and liked?

C: Oh! There’s this… um… I don’t remember the title.

T: That’s okay! Can you describe it at all?

C: Uh…there were roads, and —

T: — was it Catan?

C: shocked nodding

After a while, you get pretty good at it. But you would also get conversations like this:

Customer: Um… I don’t remember the title.

Teacher: That’s okay! Can you describe it at all?

C: Yes! You were all trying to be the best space-faring civilization!

T: Was it Twilight Imperium?

C: No.

T: Was it Cosmic Encounter?

C: No.

T: Was it Eclipse?

C: No.

T: Was it Gaia Project?

C: No.

T: Was it Eminent Domain?

C: No.

[…]

The customer gave us a difficult question. But what if they had phrased it in a different way?

C: It was a spacey card game where you do something and everybody else gets to do the same thing.

T: Was it Race for the Galaxy?

C: Yes!*

This different way of describing a game is its mechanisms (sometimes called “mechanics”): a collection of rules that drive how the game works. Mechanisms can describe almost anything, as long as it’s about function. Is the game cooperative or competitive? Is it a race to a certain number of points or does the game end from some other trigger? How are resources distributed? Do people take turns or play simultaneously?

It’s this diverse collection of rules and conventions that have been meticulously documented in the book we’ll be talking about today: Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design: An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms. That’s a bit of a mouthful, so we’ll just call it Building Blocks.

The Anatomy of a Mechanism

Building Blocks is divided into chapters, each examining a group of similar mechanisms. These chapters can be broad or narrow, looking at things like movement, turn order, actions and auctions. Chapters are further divided into specific mechanisms, each two or three pages in length. The categories aren’t meant to be exclusive: a single game can have many different mechanisms, with pieces of a game independently described in separate chapters.

For every mechanism, there are five pieces of information that the authors provide:

Name: It sounds obvious, but a huge step in identifying these mechanisms is giving them a name. For easy reference, every mechanism is given both a code (based on its chapter) and a descriptive title. As an example: games that feature traitors are identified as STR-07: Traitor Games, the seventh entry in the chapter on overarching structure (STR).

A lot of the names used in this book had already been informally established, but it’s nice to have a reference point. Finally, we have an official resource to age-old questions like “what IS a rondel, anyway?”.

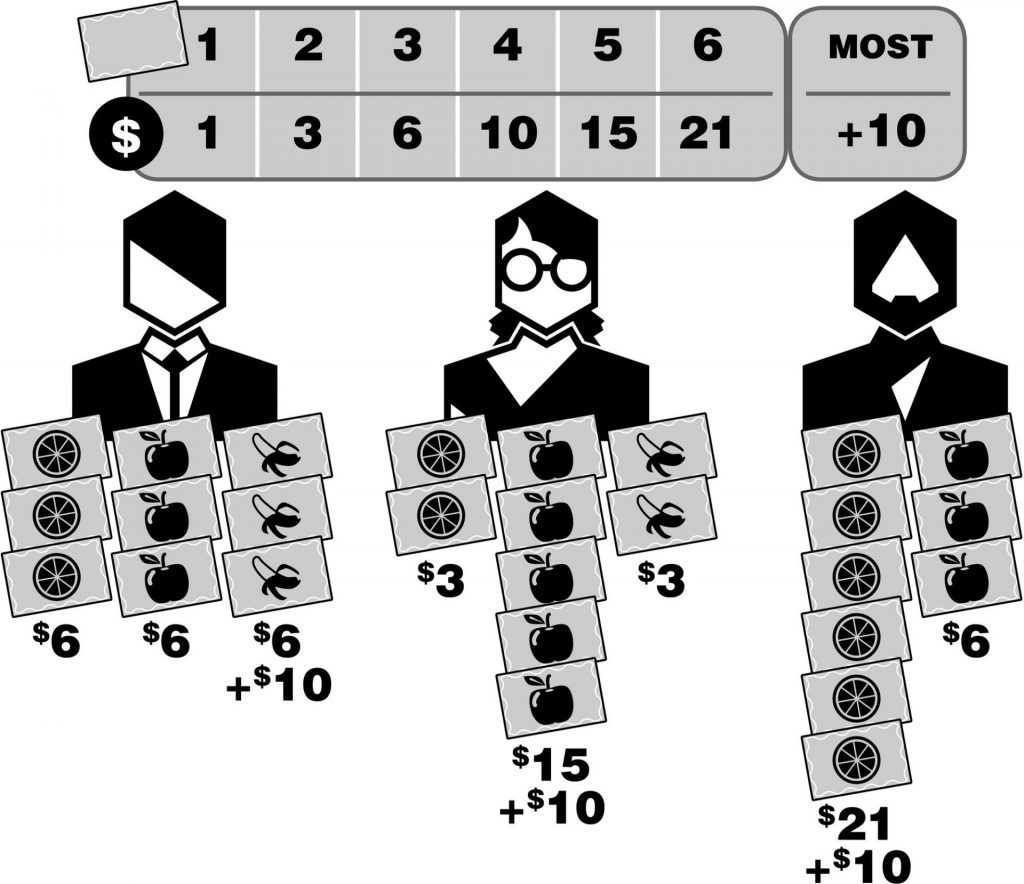

Diagram: One of the best parts of Building Blocks is that every single mechanism is accompanied by a diagram of how it works. It’s clear there was a lot of thought put into these and illustrator Daniel Solis did a fantastic job in visually representing these often challenging concepts. The diagrams are at once stylish and informative; some mechanisms could probably be figured out on the strength of the image alone. These pieces complete the book, to the point that it feels an oversight that Solis isn’t credited on the front cover.

Description: A brief outline of the mechanism being discussed. These generally strike a good balance between being concise and being precise: there’s just enough detail to get the idea without overly restricting the categories.

Discussion: By far the longest section, Discussion is where examples are explored and expanded on. This is the real meat of the book: where a Description might give you an idea of how a mechanism works, the Discussion tends to give a lot of examples as they exist in the real world. The authors share a variety of observations from field notes to history to advice for designers.

Sample Games: A collection of games that embody the mechanism. A nice touch: all the games are listed with both their designer and year, like this — Agricola (Rosenberg, 2007).

Structurally, the Description/Discussion format of Building Blocks is a smart and effective way of dividing hard definitions and more subjective observations. Outside of a couple instances when Descriptions excluded or contradicted the Discussion that followed, Building Blocks comfortably balanced its two pillars. It just works.

Successes, Failings, Audience and Objectives

I want to say at the outset here that Building Blocks accomplishes what it most needed to: through its tireless chronicling, it has formalized a common language of tabletop game design. The authors have given us a real reference point for modern board games, piece by piece. It’s hard to overstate how useful it is, both as an academic reference and for an overly curious hobbyist.

Still, there are things this book is not.

Firstly, it is not a historical text. In spite of the wealth of real-world observations and an occasional reference to how these mechanisms developed, it’s rare for entries to identify the origin of a given mechanism. They do address origins sometimes: take this example from ACT-14: Advantage Token:

“Originally introduced in the 1981 game Storm Over Arnhem as the “Tactical Advantage” token, [the Advantage Token] represents the ebb and flow of a conflict.”

…But, sadly, these observations are few and far between. As a person who loves to understand not just the what, but the how, I would have liked to see a consistent effort to find the first time a mechanism arrived on the scene. That said, it’s hard to hold it against the book: a field guide doesn’t generally give birdwatchers evolutionary origin stories. Including this content would have increased the labour in drafting this book significantly. Still, I’m sad to see it absent.

Another surprise is that the book is not just descriptive, but also prescriptive. What do I mean by that? Building Blocks bills itself as an Encyclopedia of Mechanisms. In many ways, that’s true: the book is an exhaustive study of the elements of game design and its efforts to describe the world of games is an achievement that is absolutely encyclopedic.

But what’s strange about Building Blocks is that it doesn’t just describe games. In some entries, Building Blocks will make judgements about the value of a particular mechanism, offering words of caution to designers. Take this passage on the subject of ties, taken from STR-01: Competitive Games:

“[…M]any players disdain a game that ends in shared victory. Experience-oriented designers should consider that players tend to recall how a game ended more than the rest of the play experience, and designers should seek to avoid an indecisive conclusion.”

In giving advice to designers reading the book, Building Blocks curiously departs from the realm of objectivity. It positions itself as a different kind of authority on games, evaluating the usefulness of these game elements. If these tidbits of advice had been tucked into quotes from game scholars or cited opinion surveys, that would be one thing, but they’re presented directly in the voice of the book. It’s an unusual choice, and it stands out. Because tastes, styles, and fashions change over the decades, the writers have inadvertently risked dating the work as a time capsule of what is fashionable today. It’s hard to say if the advice they give will hold true in ten, or even five years.

This brings me to our next point: who is the audience for Building Blocks? The answer to that is designers. While I was happy and engaged reading the book as a player, the design tips and tricks that pepper the book fundamentally shape the reader’s perception of who this book is for. You can contrast Building Blocks with The Oxford History of Board Games (Parlett, 1999), another major book in the hobby’s history. Parlett’s tome goes many places in its nearly 400 page chronicle, but it never gives advice. This positions Building Blocks in a curious place between encyclopedia and something else entirely. Building Blocks’ advice is particularly strange given that both authors, Geoffrey Engelstein and Isaac Shalev, are well-known designers and personalities in board game media. They have plenty of opportunities and outlets to express their views on design, and couching it in an encyclopedic work feels like a misstep. Still, the commentary doesn’t overshadow the book, and it does provide some interesting insights towards the design ethos held by its authors.

A moment should probably be taken here to talk about price. Building Blocks is basically a textbook and you’ll pay basically-a-textbook prices for it: the book retails for $85 CAD (roughly $65 USD). The price doesn’t go down by much for a digital copy. That’s not a small amount of money, which means you’ll need to be pretty curious or pretty flush to pick this one up.

As a last, strange criticism, I was a little disappointed by the book’s physical binding. In my copy, pages just sort of… fall out. That said, I haven’t seen this problem mentioned in other reviews, so that may be unique to this particular copy.

Closing the Book

Quirks aside, Building Blocks does an incredible job in taking the lay of the land. And while I didn’t always agree with its assertions, they were unerringly insightful and thought-provoking. It’s hard to imagine how much time it took to not only describe these mechanisms, but to identify them in the first place.

There is no better reference for design elements currently on the market and it’s especially impressive for a first edition. I’m eager to see how the book evolves over time as the board game world continues to innovate and the authors refine their work.

What Building Blocks gives us, more than anything, is a common language of design. It has formalized the description and categorization of all the little gears that must turn together to make a game work. This is both its most important objective and, I think, its greatest accomplishment. If you like to think about how games work — especially as a designer — then you might want to pick up this book. It’s a language I’m glad to be learning myself.

*Note: This alone could still describe several games! The second one that comes to my mind is Impulse, by Carl Chudyk. But it’s still a heck of a lot faster than the alternative.

Thanks for your thoughtful review!

Very good review! As much as I would like to own this encyclopedia, I am not shelling out that much money to get it. It would be cool to browse, though, so I may have to see if my local library could get a copy I could check out.

Good review, I found the ‘advice’ distracting and random. It was never presented with any sort of documentation or annotation, simply presenting the author’s biases as stated fact. It made me question their methodology for the rest of the work really.

As to book quality, I got the hardcover version which has held up ok, but it is essentially perfect binding glued by the side to a hardcover (when you open the book, you can see the inner spine is not adhered to the cover spine at all). This is typical of POD hardcover, so not a strike against this book, but if you buy hardcover expecting ‘case binding’, no dice.