boon (n.): a gift; a benefit enjoyed, blessing, advantage, a thing to be thankful for: sometimes without even the notion of giving, but always with that of something one has no claim to, or that might have been absent.

lake (n.): a large body of water entirely surrounded by land; properly, one sufficiently large to form a geographical feature. Or, in some board games, a syllable of misdirection in the title of a game about traveling along a river.

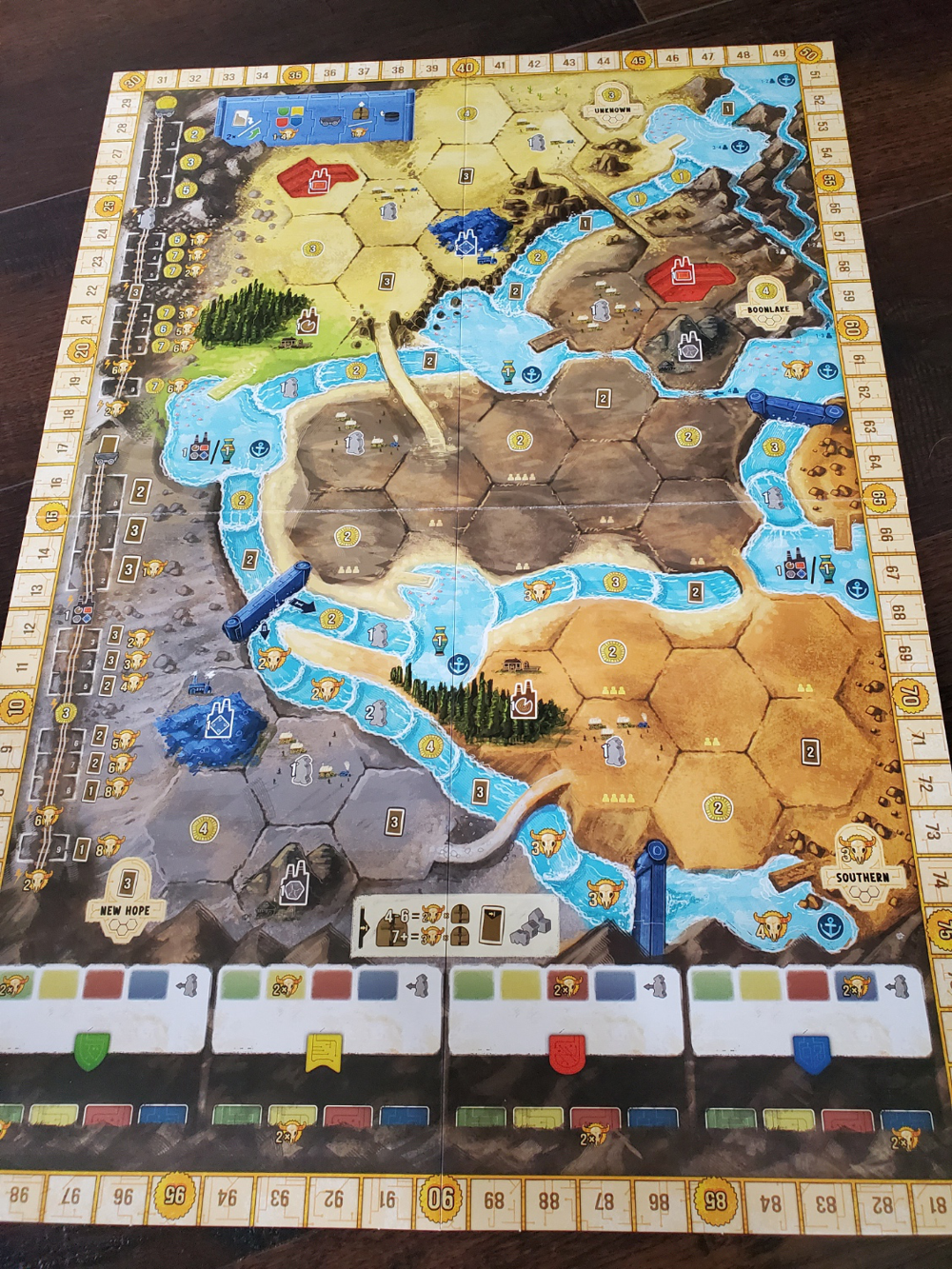

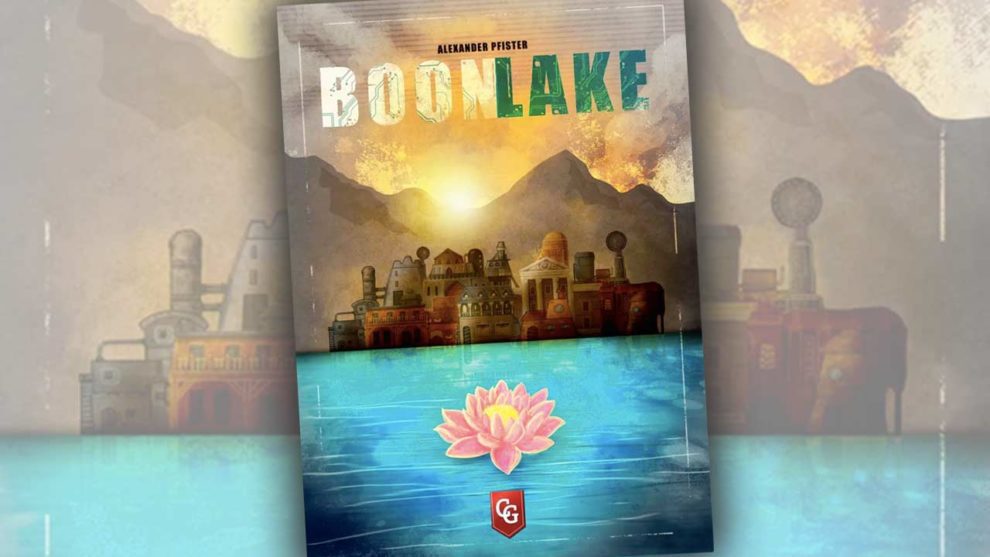

The thematic arc of Boonlake takes place on a normal sized board featuring a river that apparently travels around the region of Boon Lake (not pictured). Each player operates from their own ranch, a holding tank of production sites, inhabitants, cattle, houses, and settlements with ample room for a dozen modernizations that unleash beefy abilities. The game is a concoction of exploring the map, harvesting goodies, creating a tableau of project cards, and establishing fruitful settlements.

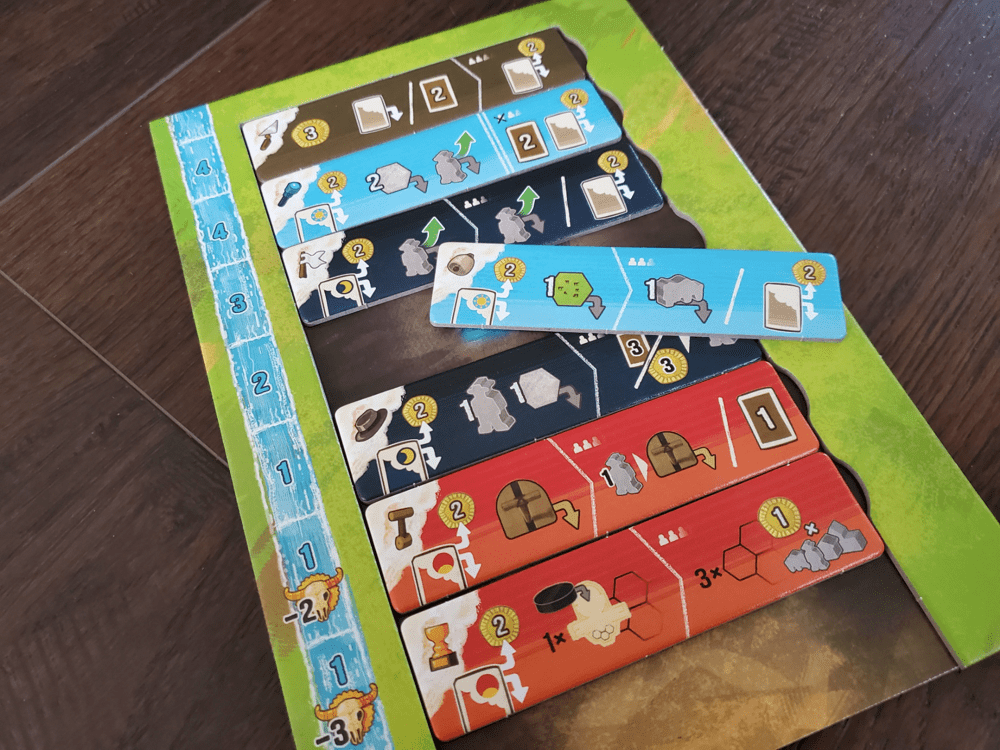

The real game of Boonlake, however, takes place on a small board holding seven action tiles. Each tile is a progression of activity that begins with the current player and radiates out to involve everyone at the table. Once a tile is employed, it is placed at the bottom of the board’s track and pushed up to close the gap. In this way, there is an ever-revolving jumble of enticement toying with players’ minds.

Boonlake’s timeline is broken up by four locks along the river. Each lock triggers an interim scoring and income generation phase, a chance to assess progress and freshen up for the coming round. Following the second lock, the players’ boats are reset to occupy the same space, creating the rulebook’s stated illusion of two rounds; but for all intents and purposes, there are four.

This 2021 release from designer Alexander Pfister and publisher Capstone Games will keep you at the table for two or more hours depending on the player count. There is a lot going on.

The action board: A tale of four tensions

As the game’s mechanical centerpiece, the action board is a tapestry of tensions:

Tension #1: Six of the seven action tiles begin with the active player playing or discarding one of the game’s three suits—daylight, sunset, or night—for two coins. The seventh simply grants three coins. The suits of the cards in hand thus generate a gravitational pull towards certain tiles regardless of the actions that follow.

Tension #2: The left side of the action tile then belongs to the active player, creating a specific draw towards needed actions and their subsequent gains.

- The Builder tile lets you play any card or draw two.

- The Pioneer tile lets you place two building tiles and either place an inhabitant or upgrade one inhabitant to a house.

- The Settle tile lets you place an inhabitant or upgrade a presence on the board.

- The Cattle tile lets you place a pasture tile.

- The Hire tile lets you gain one inhabitant and place one building tile.

- The Progress tile lets you purchase a lever (special ability).

- With the Region Scoring tile you select a bonus from one of the four regions to collect.

Tension #3: Everyone gets to do the right side of the tile, which introduces the notion of considering what everyone else will receive.

- The Builder tile lets everyone play a card or discard one for two coins.

- The Pioneer tile excludes the active player, giving everyone else two cards and the option to play or discard.

- The Settle tile gives the choice of placing/upgrading an inhabitant or playing/discarding.

- The Cattle tile gives the choice of placing a cattle or playing/discarding.

- The Hire tile involves paying cards or coins to gain inhabitants.

- The Progress tile allows everyone to pay an inhabitant to purchase a lever, or draw a card.

- The Region Scoring pays coins based on the number of wood bits in every region other than the one selected by the active player for the left-side action.

Tension #4: Every action tile grants a number of possible movements along the river based on its place on the board. Each river space gives a bonus of some sort—cards, coins, inhabitants, points, production site upgrades, vases, etc. The economy is tight enough that river spaces beckon on every turn.

The wooden bits: Getting the cows to play nice

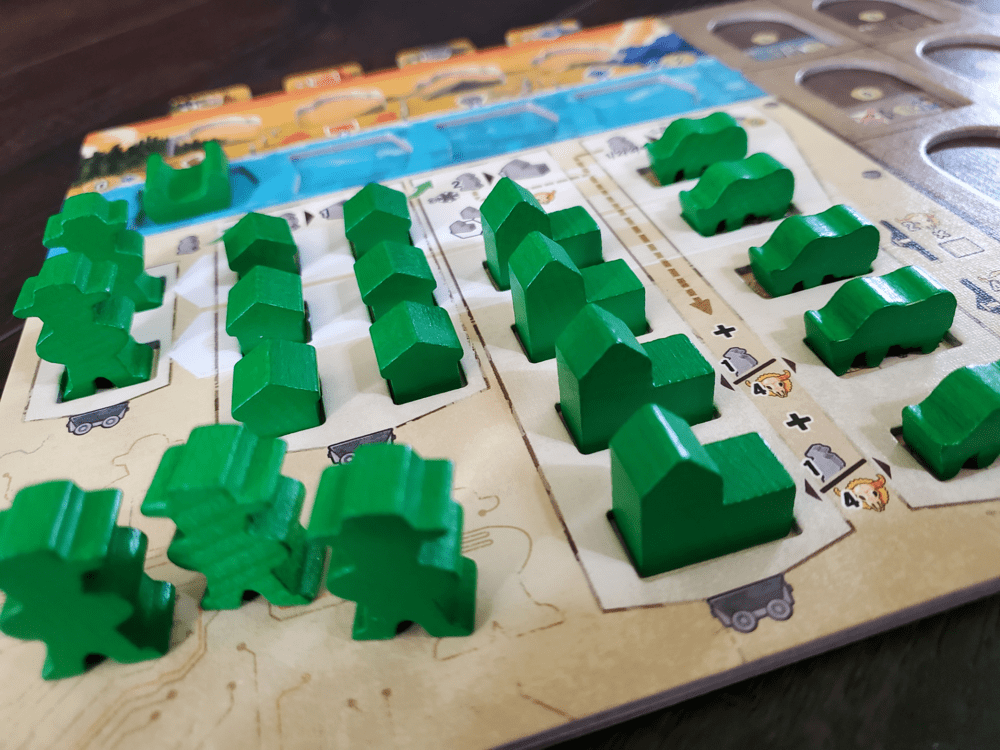

Getting twenty-five wooden bits to cooperate is the strategic heart of Boonlake. Each player’s ranch has a progression of pieces to unlock and place. Their relative position to one another determines their worth throughout the game. Ideally, cattle should be placed in pastures next to existing houses (of any color) for coin bonuses. By the time of interim scoring, they should be surrounded by settlements (of any color) for points. Players share tiles on the board, creating a mishmash of interconnected, multi-colored blessings that come alive at the locks.

Development moves from inhabitant to house to settlement. Inhabitants are also the currency for each step, making the meeples exceedingly valuable. Upgrading to a house costs one; to a settlement costs two. Placing cattle involves paying inhabitants based on the existing bovine presence. Before upgrading to a settlement, there must be at least three other wooden bits surrounding the intended house. These little requirements create a constant state of need. But at the locks, for every piece removed from the player board there are coins and points awaiting as compensation for the trouble.

Getting the cows to play nice, so to speak, is the strategic heart because it is the portion of the game most amenable to planning ahead. Players can jump in on your action, but a more populous central board is near universally a good thing, most often bolstering opportunity.

The sacrifices: Losing to gain

One feature of Boonlake that I’ve grown to appreciate is its propensity toward sacrifice. The player who is wholly averse to suffering penalties will struggle to succeed. Several tiles on the board require a pound of flesh for long-term gain. Giving up twelve or sixteen coins in the first round to move up three slots on the income tracks seems steep. But the payout is likely to far outweigh the cost. Similarly, there is a penalty of five points for dropping multiple settlements in the same board region—a cost that should be paid without flinching, provided those settlements are developed in the name of cattle, cattle, and more cattle.

The map is littered with evaluations of this sort. The true calculation of most of these sacrificial acts should leave players no rational choice but to rush headlong into debt. But there are players out there who can’t fathom such a sacrifice.

The cards: Dealing with it

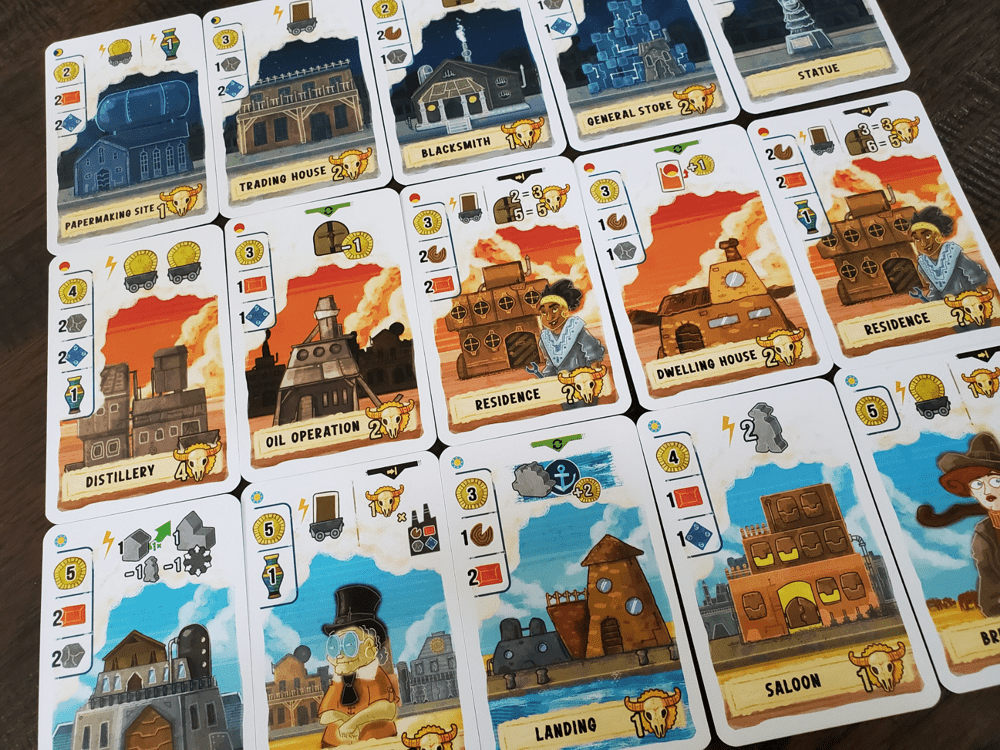

Any game with a deck of 165 cards will draw accusations of randomness, and rightly so. I would prefer to call it a celebration mirroring real life, but I acknowledge my bias here. Each card has a cost in resources—wood, loam, stone, iron, coins, and/or vases.

Resources are not collected in token form and spent. Instead, each player board has a miniature of the river with four production sites and two canoe-ish boats. Placing these boats under the resources indicates having one at hand. Movement downstream is always free, while backtracking upstream comes with a cost. In addition, players can gain markers indicating static/permanent access to either one or two of a given resource. By the game’s end, having three or even four of a resource is within reach, which is good, because the cards can be costly. Vases are the one oddball token resource, collected most often from harbor sites along the river.

Some cards grant an instant influx of coins, cards, vases, and inhabitants. Some grant ongoing bonus conditions and discounts for the various actions. Others grant endgame scoring milestones to serve strategies. Often the cards offer a combination of effects. Every card also has a point value that is part of the final score. Boonlake is a constant effort to adjust to the state of board and hand.

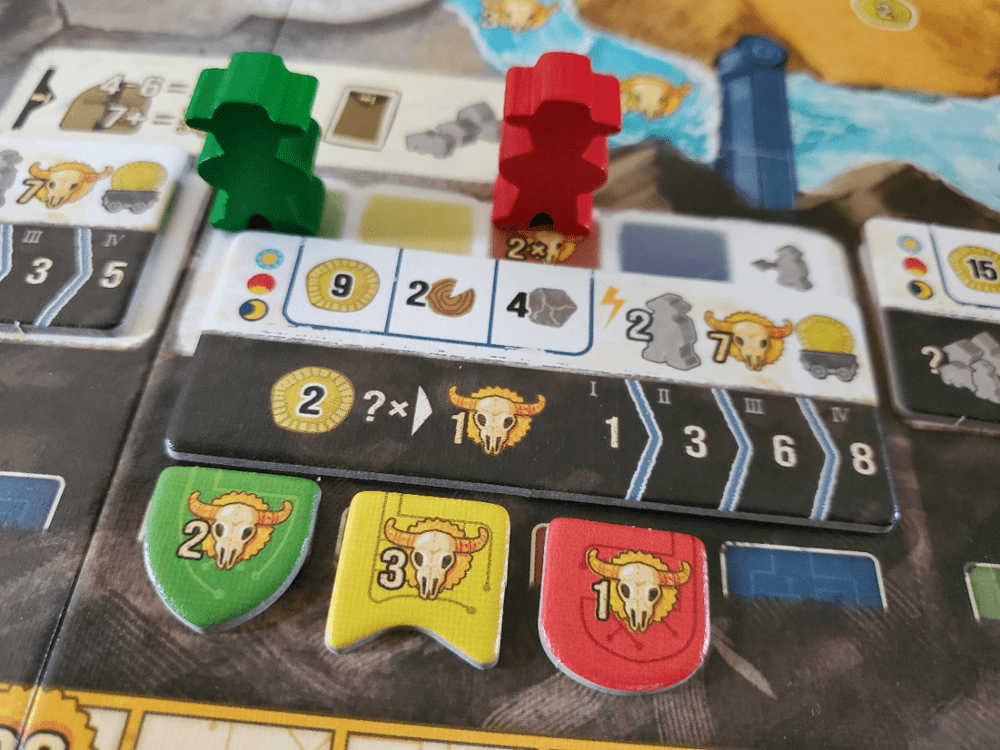

The scoring tiles: They’re brilliant… they’re confusing… they’re there

The bottom of the board contains scoring tiles that elicit a wide range of responses. Each player selects one at the beginning of the game to set in play. Regardless of the player count, there are always four available.

The top of the tile functions like a wild-suited card on a low-dose performance enhancing drug. The cost is always steep to some degree: eight to fifteen coins, two to four of multiple resources. In lieu of any card action in the game, players can activate one of these instead, each only once per game. The benefit begins with two inhabitants, though one is immediately lost for the game to mark the tile; then seven or eight points, which is nice, and doubled if the tile happens to be the one you placed; finally, the tile includes a bump along one of the income tracks that trigger at the locks.

The bottom of the tile—the scoring condition—is another story. The idea is brilliant. The explanation is confusing. As a result, though they are interesting, they are also the only aspect of the game I would jettison without thought, or at least modify for the sake of simplicity. Essentially, each tile promotes an avenue of gameplay by establishing a goal: income track, region occupation, levers, cattle, etc. Players must engage one of the four at each lock, in any chosen order. However, based on the round, the requirement to obtain the points changes. Like the top portion, your effort at your own chosen tile scores double for you alone, highly suggesting a different focus for each player. Failure results in a loss of the points.

I do like this idea, but it is—without fail—the part of the game that draws the most confused looks, requires the most clarification, and often needs to be explained multiple times, sometimes into the third and fourth rounds. There are sixteen of them in the box, meaning it would take four plays before players see all of them even once. As a result, they’ll likely need to be explained over and over again. If maximized, they provide sixteen points. In a game where two to three hundred points are within reach, the payout is, unfortunately, hardly worth the cost of growing comfortable with the mechanism when you can accidentally score half the points. I wish it were cleaner.

The locks: Putting tumblers in place

Every interim scoring begins with two actions: play a card and/or upgrade a wood bit, either one twice or once each. Playing well means planning for these actions, storing coins, setting up resources, or gathering inhabitants to prepare the way for the lock.

After the actions, players engage the aforementioned scoring tiles to collect a pittance of points. They then activate the income tracks for coins, cards, and points. Finally, the player board yields its points and coins from every space left empty by houses, settlements, or cattle. Levers reset or grant a point if unused. The region scoring markers are reset as well and play continues.

At the first lock, the river divides. Players take the top branch and make their way back towards the start. The second lock then pulls all the boats back to a spot near the start for the final descent. The third lock is the just first lock revisited, but now players take the lower branch toward the end. This final stretch of the river offers the most lucrative bonuses, but the back half of the game passes in a flash.

The tendency on the river is to move slowly at first, maximizing every early opportunity. As the game rolls on, players develop an awareness of the game state and adjust their speed accordingly. Racing to that second lock might prove a wily gesture to keep certain river spaces away from the other players. Likewise racing to the end might steal away a turn or two that could otherwise be used to catch up or extend a lead. Pacing matters in Boonlake.

The end: Of our elaborate plans, the end

Once the end is breached and players have had the same number of turns, there is one last interim scoring before the endgame tallies. Levers are converted to points based on the number obtained. Card points make up a substantial proportion of the overall total. Player boards score additional points based on the success of each player in emptying the various wooden bits.

My two-player games have pushed beyond three hundred points on multiple occasions as players mosey along the river gobbling up every available point. Four players have pushed to and past two hundred. Players who bring speedboats to the river might keep that total down, but Boonlake is a high scoring affair no matter the pace.

Boon or bane?

I don’t often make time for three-hour games. Allow me to rephrase: I don’t often make time for games that list a third hour (or more) on the box. My game groups are pretty casual and talkative, so games regularly push well beyond their intended limits. Two hours might mean three, but three hours also might mean four! As such, I can’t explain why I was drawn to Boonlake, but here I am. And I do like it.

After several tries, I’ve managed to get the teach down to around 25 minutes. An introduction to the big board, the player board, the action tiles, and the scoring tiles with a few cards handy for demonstration gets the game rolling. There will be learning on the fly. Narrating turns is helpful for a while. Thankfully, I often play with folks who talk to themselves anyway, so the obliging narration is inevitable.

The action selection board is compelling, and it is the primary reason I can get behind a game of this length. There is almost no downtime. Every decision opens a door for the other players. It may not be the most desirable door at the moment, but humanity is interesting and I enjoy being witness to the way the scene shakes down. There are constant adjustments to be made based on the opportunities presented. Sometimes you wanted the left side, but you got the right. Is it worth paying the penalty to take the action again immediately on your turn? Probably, but the psychology of it all is interesting when six other layered choices and their various river movements stare you in the face.

I suppose I should add that I am not in any way paralysis prone. In fact, I border on flippant at times for the sake of making a game’s narrative arc interesting. I like such challenges and I’m not at all driven by a win-at-all-costs mindset. Whether or not you would enjoy playing with me is a discussion for another time. For those who stare at options in agony, though, the action selection board might be physically painful. Seven tiles, a handful of cards, a board full of options. This river ain’t lazy. (It also ain’t a lake, but that’s more of a nominal point.)

The interaction of pace and the player board is engaging. As folks race to the precipice of the lock and the interim scoring, there is a scramble to get all of the cows in a row, to unlock that passive income, and to obtain the resources necessary for the bonus actions just around the bend. Occupied spaces on the river don’t count during movement, which means a movement of four can easily be a movement of seven spaces in the four-player game. Such a thing makes everyone squirm in the most satisfying way, wondering if they must face the locks early.

I’ve mostly sat with two players. Every time I play I say, this time I’m going to fly down the river, just to see what happens. Inevitably, the game beats me into submission and I find myself slowing down to raise efficiency. I can’t help it. At four players, however, I moved 11 spaces with my final three moves to trigger the third and fourth locks, deflating hopes of maximization around the table. I had the shot. There was no danger, so I took it. Two players never passed the third lock. Those are the rules of engagement. We all still scored 180-200 points.

Despite the box’s claim of 40 minutes per player, I’ve found that every player count requires roughly the same time. The river movement is key. Leapfrog ultimately means the same number of turns in the game. The player count only determines how many of those turns make you the principal agent. Five of the seven action tiles allow the other players to take their actions independent of the active player, so there’s no waiting around unless the collective action involves placement on the central board. Even in those cases, not everyone will avail themselves of that particular choice. With familiarity and trust around the table, Boonlake offers the chance to get out in less time than your average Marvel movie.

I waffle on the scoring tiles. Personally, I find them interesting even if they’re not especially lucrative. I appreciate a mechanism designed to promote diverse choices within the game, especially if it leaves the freedom to choose the order of choosing. Honestly, I wish it were more valuable so that the unavoidable confusion seemed worthwhile. As they stand, the tiles are my least favorite bit in the box because of the awkwardness of it all. The wild card tops are good, better than most cards—but not all, so some players have questioned their worth. Everyone should at least achieve their own tile for the double score, which adds another target to the experience, but that might be all.

Even at a healthy pace, overlooking some of the potential foibles, there are bigger questions to answer: do you want to play a game of light-hearted but heavy-handed exploration and settlement (minus the colonization and outright battle) that might eat up your afternoon? Do you find the action selection board convincing? Are you bovinophobic? Pfisterphobic? Hydrophilic? The answers will go a long way to deciding whether Boonlake is a match for you.

Boonlake is my first Alexander Pfister game, probably the most time-consuming title in my collection, and one of the more complex as well. At this point I know it won’t be the last. But I love the cows. I enjoy tinkering with the actions on the water, both the big river and the production sites. I doubt we’ll put it on the table every week, but it has been well received in every setting. I think it’ll stick around for the days we’re seeking out something a bit more ambitious.

Add Comment