Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

It never occurred to me before, but reading the manual for a new game is a bit like pouring over the schedule for a music festival. Prima face, that sounds crazed, the work of a desperate man trying to force some sort of unifying literary device on his game review, but hear me out. Mechanics and settings you know and love pop out at you like the names of bands you’ve been following for years. Novel combinations and thought-provoking changes to familiar dynamics are the new bands you’ve sort of heard about, or the informal stages where disparate musicians come together to jam. In both cases, there’s the excitement of the new, the unknown, a promise of the experience you’re about to have.

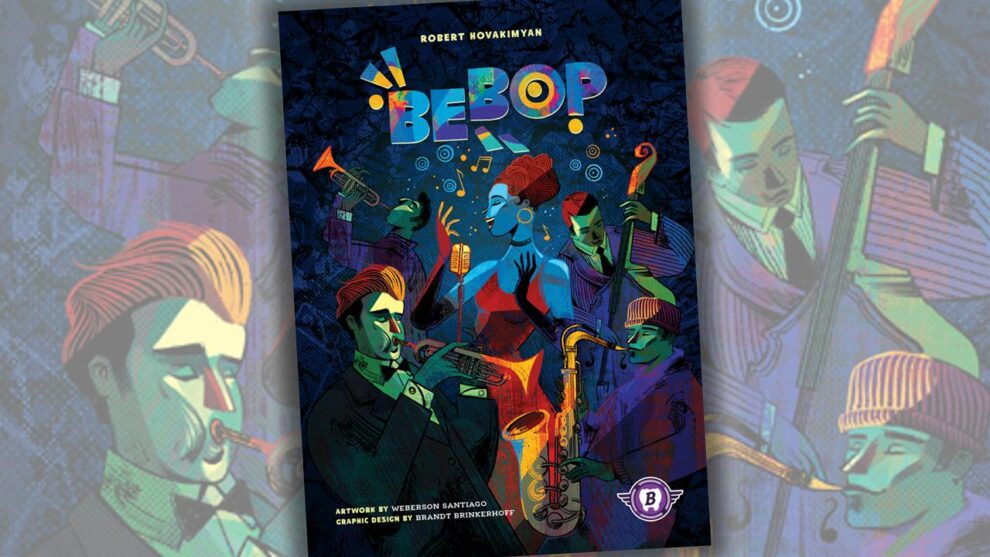

The manual for Bebop reads like a festival curated by a group of people who love all the same things as me. It’s a tile-layer, one of my favorite genres. Designer Robert Hovakimyan and publisher Bitewing Games are known worshipers at the Knizia altar. I love mid-century jazz, and Bebop is set at a jazz festival, with an aesthetic to match. For me, at least in terms of its promise, the manual for Bebop is a poster for a 2010 festival with Spoon, Tinariwen, and Camille as the headliners.

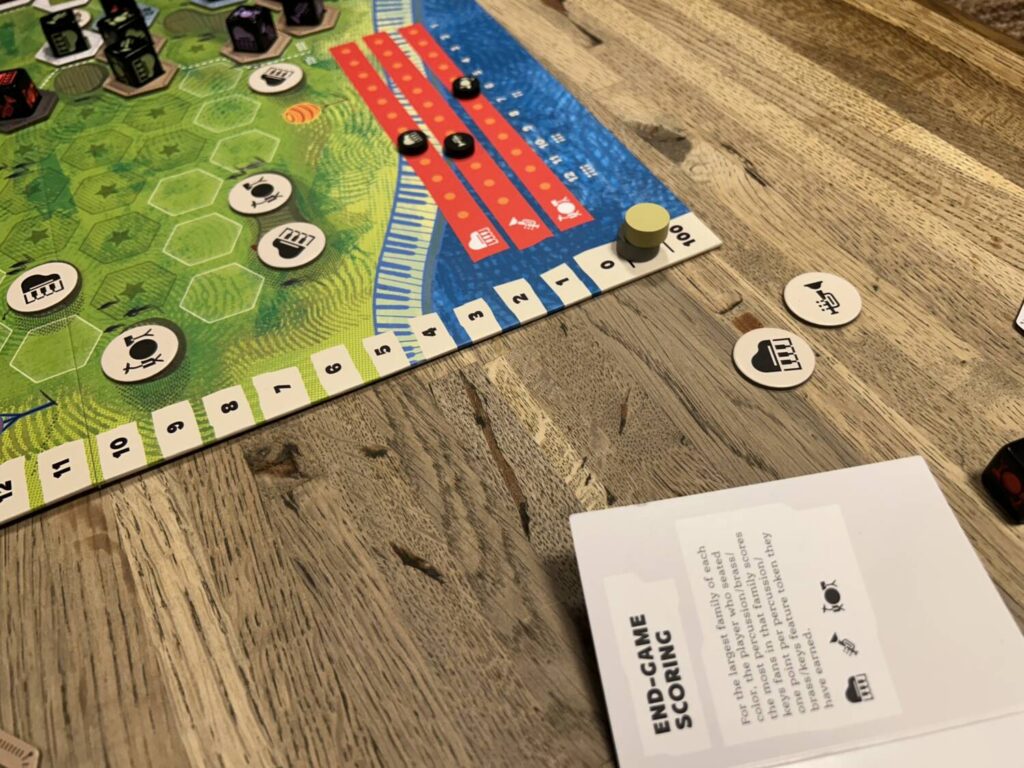

In terms of what you’re actually doing here, the board is populated by stages, each of which features solo, duo, and trio performances. As a booking agent, you are tasked with getting the right fans in the right seats to appreciate the music.

On your turn, you can either put down a seat tile, which secures a space in your name, or you can put a die into one of the empty seats you’ve previously claimed. The custom dice come in several colors, and show various instruments on each side, which correspond to the musicians performing on the various stages. A die showing a piano wants to be near a pianist. A die showing a drum set wants nothing more to watch the reincarnation of Buddy Rich run some rudiments. The color of the dice is also important. Groups in a single color, regardless of the instruments shown, form a Family, which allows for scoring to stretch out beyond the immediate boundaries of any given stage. You know how it is. If your third-cousin saw Keith Jarett record the Köln Variations, you yourself were basically there.

The two-tiered system of tile placement employed here is unlike anything I can recall having seen before. I very much like the tension of claiming a space before actually filling it, and the pressure that’s applied by the limitation on how many empty seats any one player can have at any one time. Actions are straightforward, and you find yourself more concerned with trying to figure out what you want to do with your turn than trying to figure out how to make it all happen—an issue that plagues Bebop’s crowdfunding cousin, Shuffle and Swing.

Beboop

A minor quibble: according to Bebop’s lore, you’re playing as booking agents, trying to get your customers seats in front of their favorite acts. This makes no sense. Booking agents have nothing to do with who attends a show. Booking agents work either for artists or, more commonly, for venues, and are responsible for handling the scheduling and logistics of performances. They are often involved in promotional materials, and are likely responsible for inviting members of the press, but that’s both literally and metaphorically a different game. If you were playing as booking agents, you’d be trying to place your artists in the right venues. That theme sounds like a better fit, come to think of it.

This is not inherently an issue. Many games don’t make sense if you think about the setting for more than a minute. In the case of Bebop, though, I think the disconnect is indicative of a larger problem. Between the name, the box—that box cover is gorgeous, Weberson Santiago deserves a glowing review all his own—and the general aesthetic, Bebop promises a jazzy time. You would expect it to feel improvisatory, full of dynamic realizations and seat-of-your-pants tactical pivots. Though the scoring system encourages some degree of predation, Bebop feels much more calculating than that. As one of my friends joked, “I was excited for a jazz festival, and what I got was Ticketmaster: The Game.”

As for the Knizian influence, Bebop feels most similar to Babylonia, which has never worked for me. Unlike many of the good doctor’s tile-laying designs, several of which number among my favorite games of all time, Babylonia often feels strangely solitary. Every time I sit down to play it, I feel anticipatory excitement at the idea that this time might be the time everything clicks. Maybe this will be the game when people aren’t simply forming large groups, but tactically zooming around the board. It never is. Every now and then, someone else leaves you an opening to take advantage of, but otherwise, I’m making my big group and you’re making your big group and she’s making her big group and he’s…you get the idea.

Bebop falls into the same position. Large groups are fundamentally better, to the extent that, even though the game allows for piggybacking, there are seldom few opportunities for dramatics, for reversals, for surprises. Maybe that’s my fundamental problem with both of those games, when you get down to it. Neither provides a particularly dramatic kick.

Bebop isn’t, by any means, a bad game. Like I said, I think the two-tiered tile-laying is a wonderful idea, and the production, as always with Bitewing, is top-notch. Something is missing, though. Despite a robust lineup, this is a festival where I didn’t hear all that much music that excited me.