Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

It was my turn during a recent four-player game of Axon Protocol, a game I first saw at last year’s SPIEL event in Essen, Germany. I had to decide which of the 15-ish characters on the board needed to be hacked to best help ARES Corporation, my nefarious murder and augmentation shop.

Using the services of the Serial Killer—yes, Axon Protocol is that kind of game—I decided to murder one of the other characters in my space, the Reporter. After adding a Violence token to the Serial Killer, I went about my merry way and played a Software card to add more options for a future turn.

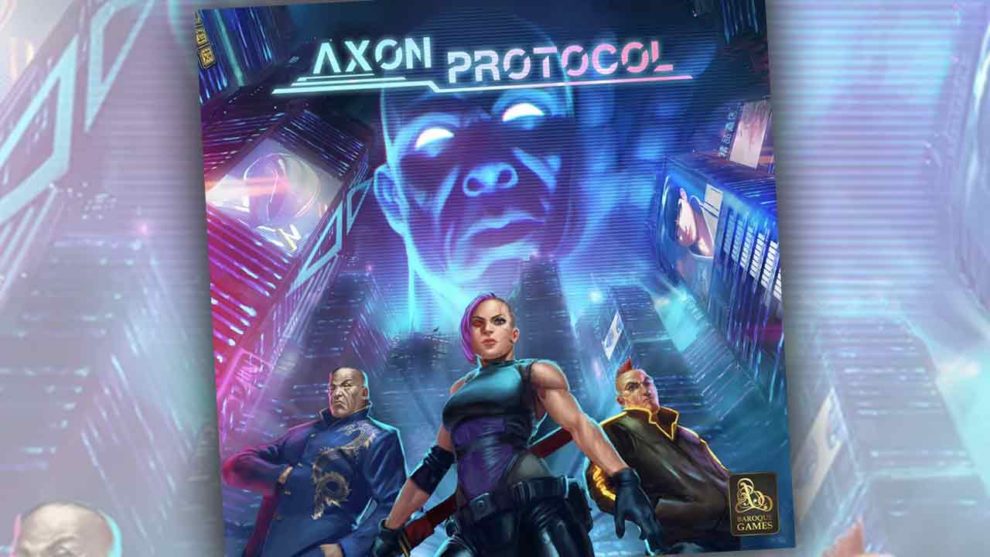

So it goes in Axon Protocol, a cyberpunk worker manipulation game set in the fictional world of Nexus City for 1-6 players that runs anywhere from 45 minutes to…well, longer. The game’s setup is actually pretty simple—score the most points by trying to add tokens to the board representing the things your personal corporation values most—and teaching the main actions of the game takes only a few minutes.

The world building, the artwork, the names for the characters…there’s something here. Working in a world that feels not unlike movies such as the French action film District B13 or the apocalyptic American thriller Escape from New York, Axon Protocol has all of the makings of something really great.

But the end result feels like a package that could have used some more time in the oven.

Drugs, Murder, Kill

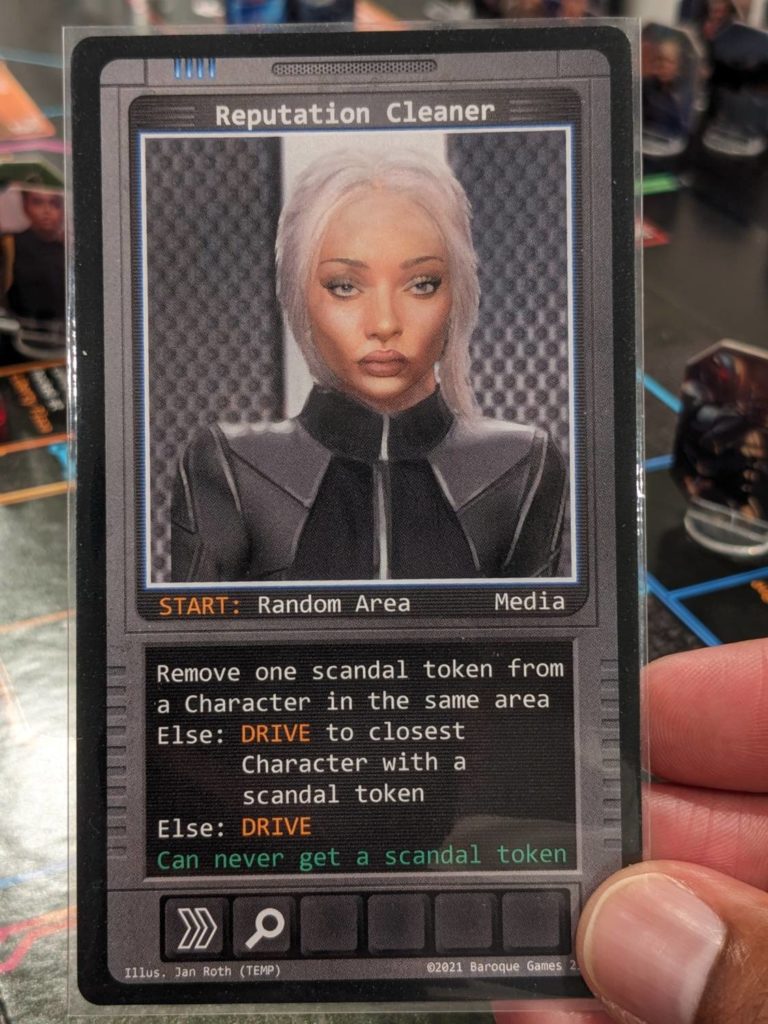

Players operate as corporations with the ability to hack into the routines of Nexus City’s regular citizens: Cop, Reporter, Rockstar, Yakuza, and about 30 other familiar-feeling archetypes. These citizens go about their day-to-day lives, which in the case of the Corporate Assassin is to murder people from time to time. The Rich Kid moves from area to area spending money. The Private Investigator investigates things.

You get the idea.

The map of Nexus City looks a heck of a lot like Manhattan, the setting for the 1981 cult classic Escape from New York. Further fan service: the prison is called Fort Plissken, after the lead from the film, Snake Plissken. There are 20 different areas on the board, spaces that can be shared by any number of the characters currently in play.

During setup, characters equal to two times the number of active players are placed semi-randomly on the map. Each of these character cards are divided into two sections—their normal routine, which they will do if activated and not hacked, and a line of symbols showing their available actions if a player decided to hack into that character’s brain and make them do something else.

Turns, then, are simple. Players will normally activate any previously-unactivated character from that round and do something with them. If they trigger a character’s routine, they follow a series of commands on that card until they hit a legal option for that turn. Otherwise, the active player will burn one of their Software cards—cards with special abilities that could be played for those abilities, or as a discard cost—to hack a character and do something more interesting. Other turn options include taking the first player token, UNO-style reversing the turn order, or “phishing” to add another character to the map.

Each player is incentivized to get tokens onto the map, ideally in one of the two token types that player will score at the end of play. There are six different types overall: Augments, Drugs, Products, Data, Violence and Scandal. (This DOES feel like New York City in 1997, after all.) That means that usually, you’ll be hacking characters to make them do things that get Drugs and Scandal on the map if that’s what your corporation needs for end-game points.

On some turns, actions are vanilla—move a character to a section where, hopefully, they can be murdered on a future turn to generate Violence tokens in the city, for example. Some turns—and this was rare in my plays, but it’s still possible—provide a chance for a handsome chain reaction. You might get one or two drug tokens onto a character, which triggers a bump in the drug market that unlocks another resource that has to be placed on another character, which then makes them a target for the next player to potentially overdose a character that you want removed from the game. (When a single character is holding 3+ drug tokens, they automatically “OD.”)

Axon Protocol provides some chances at real gaming moments thanks to a world that feels like it might be more alive. But there are two things I have not described yet: the card text and the scoring conditions.

Oh boy.

“Wait, You Won the Game 6-5?”

Axon Protocol’s minor sin is the scoring.

At the end of play, after a ton of jostling to get the resource tokens you need on the map and killing off characters that are holding tokens you don’t want your neighbor to score, you’ll be shocked that scores are so low.

The HIGHEST score I’ve seen in a game of Axon Protocol was 9-7-6-4. One of my two-player games was 6-5. While the game supports a max of six players, I don’t think I want to see it at that count, for reasons that I’ll come to next.

Here’s how you score: you’ll get one point for every two resources on the map or on an active character. You could take a major risk once per game to “monopolize” your corporation; this means that you commit to only scoring one of the two token types you have access to, and each of those tokens will count for two points per token. That also makes you a massive target with other players who have not monopolized their company. Each player also can score one point per “permanent” victory point token, which can be earned on the scoreboard mat when moving resource market tokens up on a grid in the center of the play area.

Players then lose points for any data tokens that are in their corporation space on the map.

For all of the work that is put forward to get tokens out on the map, it’s a shame that scoring feels like such a slog. I’m all for games that feature an “every point matters” mechanic, in games such as Dune: Imperium. But the scoring feels off in Axon Protocol.

The major sin of Axon Protocol is the card text. Each character card has a routine that is spelled out in plain English. But, there are a LOT of words on many of these cards. Then, you have a different set of problems. There are usually 10-15 characters in play at any given time (particularly at higher player counts). Depending on your seating location, you’ll basically have to stand over the character card area of your table. Each card has white text representing their routine, and green text representing passive abilities which are always present.

Reading all of the text on these cards, EVERY TURN, is a chore. The ask for all players is that they will regularly need to consult the player aid because each of the six resources operates a little differently…and there are FIFTEEN different icons in the hacking area of each card, with each character having access to as many as six of those 15 icons.

Whoa, is right.

Baroque Games, and designer Jan Roth, didn’t do the game any favors by only including one player aid. (Our review copy is a prototype, so this will hopefully change when the final product hits shelves.) Even when paired with the strangely dense instruction manual, there are not enough player aid resources to go around when players want to study up in advance of their next turn.

That also means that games often come to a complete halt, when considering how to maximize a turn or get a token onto the map in the hopes of scoring it at the end of play.

Do Your Chores

Axon Protocol gets a lot of things right, even with the not-final version of the game that I played.

The variety of characters in Nexus City is fantastic, and I really love the art style employed here. The standees for these characters help bring the production to life, and I liked tracking the amount of Scandal, Drugs and Products in the market from turn to turn using the scoreboard tool.

The game’s main actions are easy to teach, and describing the ways characters can move around with the board’s visual aids made getting Axon Protocol to the table fairly simple. Despite all of that card text, games usually could be completed in about two hours, which isn’t too bad for board games in general. That’s just too long for this board game.

Games of Axon Protocol usually felt like a chore to work through. There’s just not enough meat on the bone to warrant this level of round-to-round manipulation. It’s interesting—at the end of each round, scores are calculated to ensure that the player in last place gets to go first in the next round.

That usually meant a fairly comical routine would take place: one player might have no points, maybe two, at the end of the first round. The player with a “massive lead” might be ahead 2-1-1-0. I’m not sure that there is a large-enough first player advantage to warrant flipping the turn order, and I’m not sure it’s really worth going first in a game where you have the choice of a dozen workers available to do your bidding in the next round.

The verdict that was most troubling: none of the five different people who sat with me across my three plays wanted to play this one again. Most players landed in the middle during our roundups; everyone liked the production (even for a prototype, this was pretty solid save for the small cardboard chits used to denote an activated character). The artwork is great. Even though there aren’t enough of them, the player aid is fantastic, really fantastic.

The gameplay was the main miss. Axon Protocol was a worthwhile journey for me, as a junkie of worldbuilding like the one on display here. But it’s not a game I expect to return to the table.

Add Comment