Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

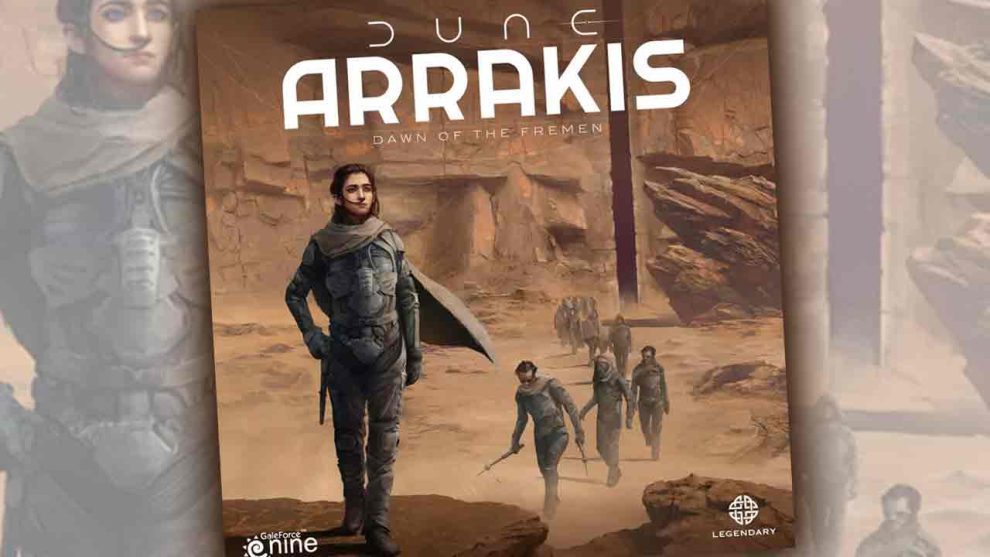

Arrakis: Dawn of the Fremen is the third major board game published in the last few years to make use of Frank Herbert’s Dune. First came a long-overdue reprint of the 1979 Dune game, a sprawling affair of area control and negotiation. Then came Dune: Imperium, which I’ve never played. Now we have Arrakis: Dawn of the Fremen, a slightly less sprawling affair of area control and negotiation.

Gale Force Nine, the publisher of the Dune reprint and Arrakis, seem to be making the most of two recent rights acquisitions. Arrakis is a reimplementation of Borderlands, a 1982 game from designers Bill Eberle, Jack Kittredge, and Peter Olotka. That’s three-quarters of the team responsible for 1977’s Cosmic Encounter and, you guessed it, the original Dune. The tide is in folks, catch ‘em while you can.

Phases Phases Phases

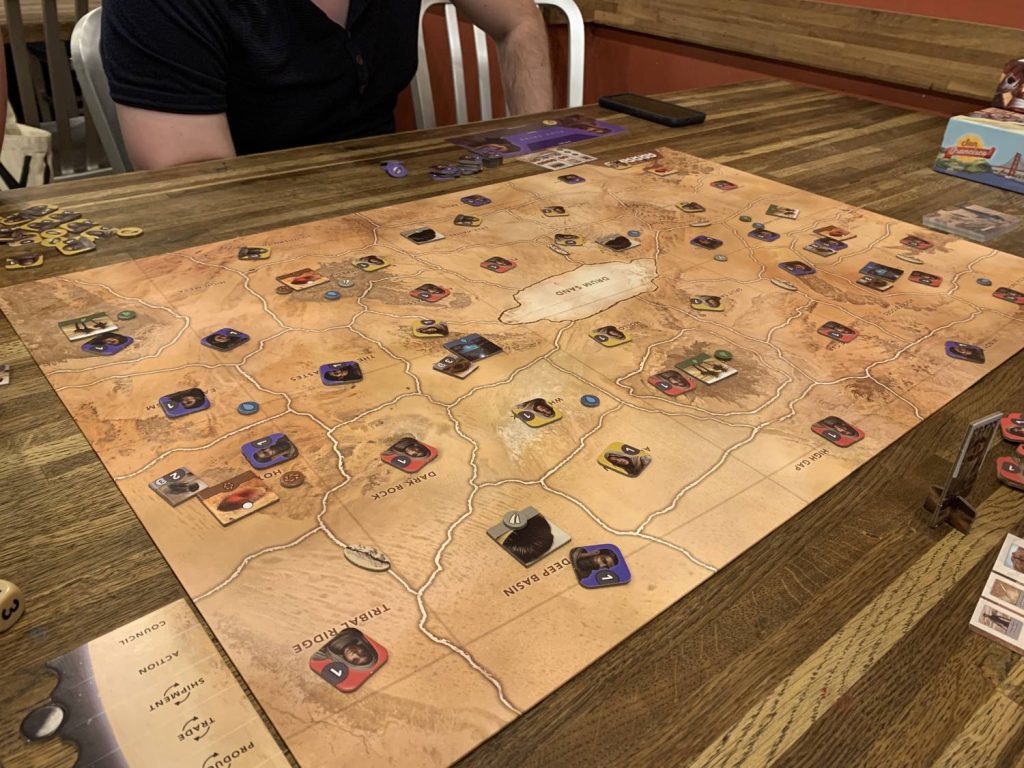

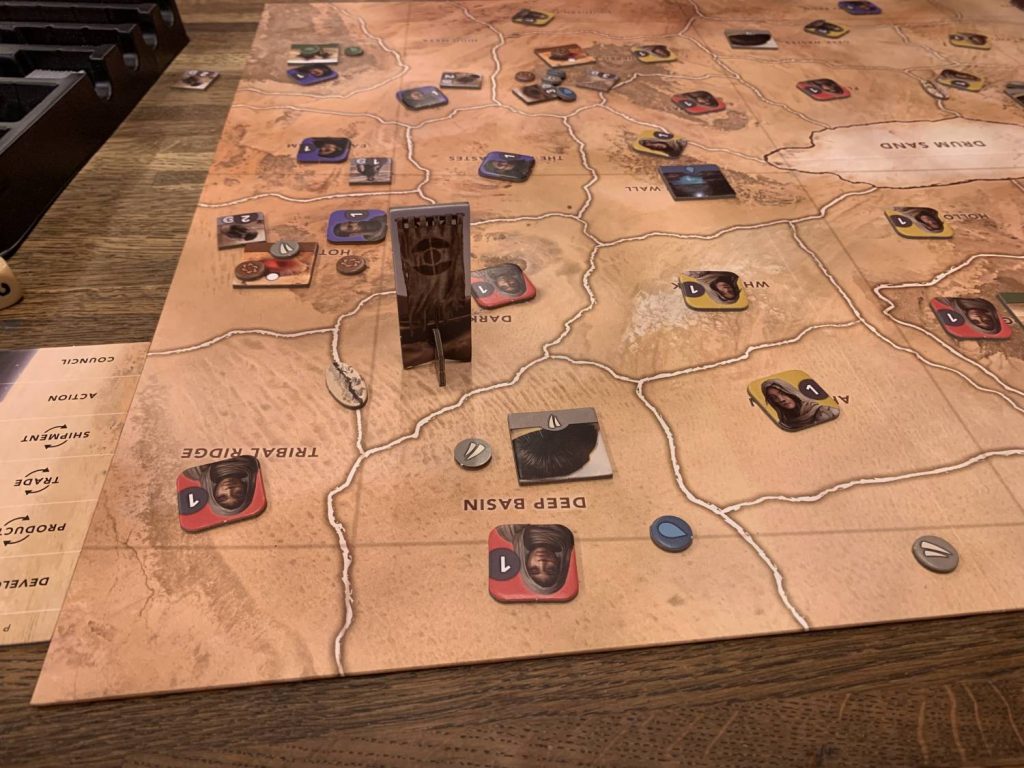

Arrakis: Dawn of the Fremen covers events on the planet Arrakis, the source of the spice that drives the Duniverse, centuries before the novels take place. Never having played Borderlands, the mechanics make for a good thematic fit. Players struggle for resources and territory. The goal is to control a certain number of sietches, the basic Fremen habitational unit. You develop sietches and various pieces of technology by shifting your resources from place to place and consolidating.

Each round consists of a series of phases, during which players will complete various tasks. Every action phase, for example, players choose one of four combinations of actions. You can either scavenge, picking up a card that will give you some variety of bonus, or attack, and then you can either ship, moving resources and strength around the board, or attack.

The scavenge cards have a variety of effects, and if the outcome of the game itself didn’t seem so predestined—more on that in a minute—I would describe them as “swingy.” That’s in keeping with the general design philosophy of the designers, though. It’s hardly a surprise. They’re not here for balance, they’re here for drama.

Interesting Ideas

Some phases during a round are subject to the whims of a die. What resources produce, whether you can trade, and whether or not you are allowed to turn those resources into shiny new crysknifes and stillsuits will depend on the die. Certain results allow everything to happen as normal. Others prevent certain phases from occurring. Yet others allow that round’s starting player to decide whether or not a certain phase will take place. It’s an interesting idea.

Setup is incredibly important, since your troops don’t move. You can only claim new territory by winning conflicts. Players go around the table, placing one troop at a time anywhere on the map. If you set yourself up in the wrong position, you’re done. I say setup is important, but that’s an understatement; it’s not difficult to map out the course of the entire game from a quick glance at the map before play starts. An interesting idea.

I enjoy the combat system. In a hard break from Dune, the combat here is deterministic, with no hidden combat cards or troop bidding. The drama comes from whether or not third parties will contribute their strength to the attacker or the defender. Because all the information is out in the open, moving offense around is also moving defense. You can put a number of resources into attacking a given location, but it will open you up to attack elsewhere in an unusually direct way. An interesting idea.

If the aggressor succeeds, the vanquished defender loses the targeted territory, along with any resources and goods therein, but they gain a Water Debt. Water Debts can be spent to ship resources through enemy territory without permission. Two Water Debts can be used by a defender to stop any one player’s strength from impacting a conflict. That prevents too much dogpiling. An interesting idea.

Each round ends with a council. All players discuss the state of the game, and can suggest changes. You are encouraged to change whatever rules you want, so long as the entire group agrees. This is technically true of every game, of course, but few spell it out explicitly in the manual. You can also agree that the board state is irreversible and end the game with a declared winner. Again, an interesting idea.

That’s what Arrakis seems to be, a series of interesting ideas rather than a coherently engaging design.

A Snowball’s Chance in Arrakis

All of these interesting ideas add up to a game that feels like it could be extremely compelling if all of the people playing understood every nuance. The original Dune feels much the same to me. The difference is, I think the original Dune is worth that work if it’s your brand of bread. It has a heady mix of paranoia, a certain flexibility of trade economy, and an overall elastic play experience that, while not being to my tastes, is unique.

Arrakis: Dawn of the Fremen doesn’t feel unique. Despite all those interesting ideas, despite the fact that Eberle, Kittredge, and Olotka know drama is their brand, it feels pretty bland. At no point does the divine spark issue forth from this board. At no point do I find myself thinking of a move as inspired. There are no surprises. There is only the steady and inevitable. That the game has a massive snowballing problem doesn’t help.

To put it simply, the game itself isn’t interesting, and it isn’t fun. What’s in the box? Pain.

Add Comment