Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

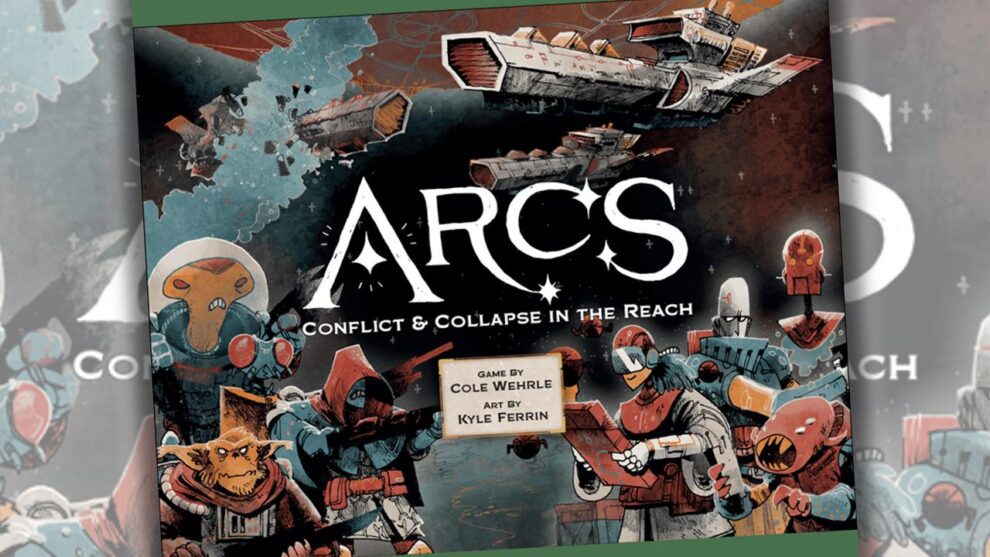

I don’t know that I’ve ever played a more divisive game than Arcs. Cole Wehrle’s latest design, unquestionably the most-anticipated board game of 2024, won’t even be out at retail for another two months, but seemingly everyone has already played it, and seemingly everyone has an opinion. Most of those opinions are strong.

This is becoming de rigueur for Wehrle releases. While Root and Pax Pamir are consensus classics—even the people who don’t like them wouldn’t generally argue that they’re bad—Oath had a stark divide between fanatics and detractors. You don’t meet many people who think Oath is “fine” and have nothing more to say on the matter. Arcs, from my experience so far, is plowing a similar furrow. For every “I enjoy Arcs, and would happily play it any time” or “Arcs is the greatest board game ever made” you hear, there exists an “I get what it’s trying to do, but I don’t think it does it” or “Oh, I hate Arcs” to balance it out.

It is now my job to not only reconcile these viewpoints, but to assign an objective numerical value to my play experience. It is my job to solve Arcs. Sure. Simple enough.

The Short Arcs of History

For all its flash, for all its ingenuity, the core of Arcs operates wholly within the limits of a traditional 4X game, the subgenre dedicated to claiming space, accumulating resources, and blowing sh!t up. During your turn, you might build and repair ships, cities, and spaceports; move your fleet through space; tax cities for the resources they produce; spread influence among the Guild and Vox cards in the market so you can secure them to your cause; and, as promised, blow sh!t up.

What makes Arcs so unusual is the means through which you accomplish all this: Arcs is a trick-taking game. Well, ish. It’s not not a trick-taking game. The deck consists of four suits, with Wehrle-riffic suit names like Administration, Aggression, Construction, and Mobilization. Each round, players take turns playing a card and performing actions. The actions you can take are determined by the suit of the card you play. If you put down a Mobilization card, for example, you can move your ships or spread influence, while Aggression cards allow you to battle, move, or secure cards in the market, which either trigger one-time events or get placed on the table in front of you as part of a haphazard tableau.

In addition to a value between 1 and 7, every card in the deck has a certain number of pips, inversely related to the value. Those pips correspond to the number of actions you get to perform. If I have the initiative and lead—play the first card—with the 1 of Administration, which has four pips, I can do any permutation of four tax, repair, and influence actions. The 7, on the other hand, has but a single pip. Its strengths will become clearer in a minute.

Subsequent players are in a tougher position, and find themselves with three choices:

- Surpass, playing a higher card in the led suit. This is the easiest, most efficient path, since you too will get to perform one action per pip.

- Pivot, playing a card of any value in a different suit in order to perform a single action listed on the played card.

- Copy, playing a card facedown to perform a single action listed on the lead card.

When you play your card, you can also spend resources. There are five in the game: Material, Fuel, Weapon, Relic, and Psionic. Rather than representing a cost you have to pay—I don’t need to spend Material to build a city, I can just build it—the resources in Arcs grant you additional actions. A spent Material lets you perform a free build action. Fuel lets you move. Relic lets you secure a card from the market. Psionic lets you perform one of the actions on the led card. Weapon is a little different. Instead of granting you an additional action, it allows you to treat your card as though it included Battle as an option. From a balance perspective, this is wise.

Resources are a primary method through which Arcs mitigates the entropy of card draw, and they are one of my favorite parts of the design. Since resources are primarily gained through taxation, and the resources produced by cities are determined by the planets on which they are constructed, you have long-term ways of setting yourself up to always have certain actions available. If you have a robust network of cities, you could conceivably spend most of your card actions taxing, and use the resulting resources on subsequent turns to take care of other concerns.

I enjoy the contours of the cardplay decisions. When you lead, the card you play is setting the timbre of the entire round. You’re not only thinking about what you want to do, but what everyone else can do with the same suit. If I kick things off with Aggression, it’s going to be a turbulent round, and I’m the one who allowed it to be so.

Once each player has their turn, the trick is cleared off the board—nobody takes it—and the initiative goes to whichever player played the highest card on suit during the round. Players who find themselves short-suited aren’t out of options for gaining the initiative, nor are players with nothing but a handful of low- or mid-value cards. So long as you didn’t lead, you can Seize the initiative by playing an extra card facedown. Given that each Chapter lasts until every player’s hand is empty, discarding an extra card is a high cost to pay. You’ll spend a turn in the passenger seat, watching everyone else play. It is often worth it, though, since the player with initiative is also the only player who can declare an Ambition.

Ambition Greets You Like a Naughty Mate

Ambitions are not only the primary means by which you score points in Arcs, they are in fact the only means by which you score points. There are five of them: Tycoon, Tyrant, Warlord, Keeper, and Empath. Each represents a different scoring criteria, and each rewards the players with the most and second most in the corresponding category.

Tycoon rewards reserves of Material and Fuel.

Tyrant rewards Captives, which are gained by taxing enemy cities and by securing cards from the market that other players have also been trying to snag.

Warlord rewards number of Trophies, the enemy ships you’ve destroyed in battle.

Keeper rewards Relic icons.

Empath rewards Psionic icons.

None of these Ambitions are worth anything unless someone declares them.

Every card, in addition to its value and pips in the upper left corner, has an Ambition icon to the lower left. These icons are consistent across values. The 1’s are blank. They’re no good to you in this context. The 2’s feature the Tycoon icon, the 3’s Tyrant, and so on. The 7’s, which are only used in a four-player game, are wild. When you lead, you can choose to declare the Ambition on your card before performing your actions. If I play a 2, for example, I can then declare the Tycoon Ambition.

If I do that, a few things happen. First, I place the “Ambition Declared” token across the top of my card, which zeroes out its value. I still get to take my full complement of actions, but other players are now free to play any card they want from the same suit. It’s much easier to Surpass a 0 than it is a 4 or a 5. Then I take the most valuable remaining Ambition token—there are three in total—and put it in the corresponding Ambition box on the right side of the board. This token tells everyone how many points first and second place for that ambition will get.

At the end of the Chapter, when everyone has run out of cards, all the declared Ambitions get scored. In this case, for Tycoon, we count up the number of Fuel and Material tokens each player has in their Resource slots and any additional icons on their secured Guild cards. The top two players score according to the numbers shown on the points token(s). I say “token(s)” because the same ambition can be declared more than once per round.

That may seem like an easy way for a player who’s ahead in one category or another to wrack up a whole bunch of points, but there are risks. You are painting an obvious target on your back, and if there’s anything a Cole Wehrle game lets players do, it’s gang up on someone with a target on their back. Ask anyone who’s ever had a six or seven point lead early on in a game of Root if they enjoyed the next round.

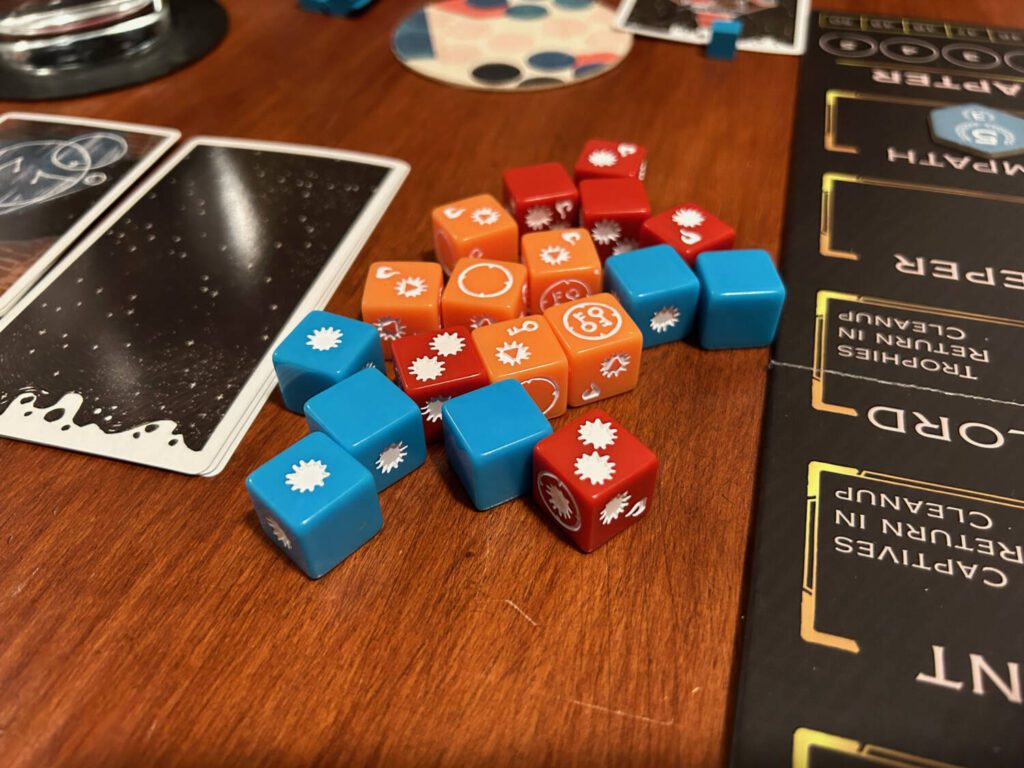

Put Your Hands Up, It’s a Raid

The combat system in Arcs is phenomenal. Everything, both offense and defense, is on the dice rolled by the attacker. I attack you. I pick dice. I roll. I assign damage to my ships, you assign damage to your ships, we move on. It’s clean, is what it is. Battle happens when a player sharing a space with another player uses the Battle action. The aggressor takes one die for each ship they have in the region, choosing from three varieties of dice. Skirmish (blue) and Assault (red) dice both focus on dealing damage to defending ships. Assault dice deal more damage, but there’s also an elevated risk to the attacker.

The third variety of dice, the Raid dice, are a bit different. These tantalizingly orange cubes of molded plastic can only be used when attacking a city or a spaceport, and they focus on petty theft. Half the faces of each Raid die include key icons, which can be used to steal from your opponents. If I raid your city with four ships and get three keys in the process, I can use those keys to help myself to some of your resources and Guild cards.

A player foolish enough to declare the same Ambition twice in a round can quickly find their fortunes reversed. You can have as much of a lead as you want, but if other players are chipping away at that lead while simultaneously adding to their own position, you’re gonna have a bad time.

Everything in Arcs is temporary. Your resources, your Guild cards, your cities and spaceports. It can be a mean and swingy game. Like most Cole Wehrle designs, it does rely on the players at the table having some sense of what balance means, and whether it’s really worth punching that player in the mouth again. Maybe they’ve been punched enough.

A Bad Hand

An action economy based on card draw and a combat system based on dice rolls. Some of you, I have to imagine, are viscerally turned off by what you know of this game already. If that is your instinct, trust it. Nothing about how Arcs plays out is going to change your mind. If you go into it expecting or desirous of an Eclipse-type experience, looking for a game that rewards long-term strategic thinking, you’re going to be disappointed. Arcs is fiercely tactical. For its weight—you basically know all the rules now—it’s probably the most aggressively tactical game I’ve ever played. I get why people are bouncing off of it.

At the same time, after countless conversations with friends who Simply Do Not Get It, I find myself unconvinced of their criticisms. Across five or six games of Arcs, I have yet to find myself in a position where I felt I could not do anything. I’ve never felt hemmed in by drawing a hand with which I couldn’t declare anything to my benefit. Instead, I maneuvered my way into doing well in the Ambitions declared by others. I have won each and every game of Arcs that I have played by a wide margin, playing against people who are generally very good at games and have played Arcs before. That tells me this isn’t anywhere near as down to luck as many of its detractors feel. I’m not that lucky.

It could be that Arcs requires a very specific sort of permutational awareness. In my most recent game, I found myself thinking of an unlikely point of comparison: Alexander Pfister’s 2014 Spiel des Jahres winner Broom Service. Like Arcs, I have never lost a game of Broom Service. Across 5-10 plays over the years, I have always won, and by a comfortable margin. That too is a game in which optimal “strategy” revolves around being awake to ever-diverging paths of possibility. It is, by and large, a game that lives and dies within the marginalia of your tactical choices. Arcs, for as different a game as it is, feels the same. Being well-positioned to do the perfect thing isn’t how you win Arcs. Being well-positioned to do the most things is.

Last night, I compared my experience playing Arcs to floating on my back in a salty bath, letting the spirit move me however it may. Do I have strategies? Yes, of course. Do I have turns when I get frustrated or stymied? Absolutely! The key seems to be to brush that off and see what else you can find. In my most recent game, for the first time, I drew a hand that didn’t provide any avenue into the one action I wanted to do on my turn. I looked at it for a moment, thinking to myself, “Do the people who dislike this game have a point?” But within moments that was gone. I surrendered myself to the waves of the round.

Is it a bad hand, or is it a challenge? Your experience of Arcs may boil down to how you feel about that question.

Leaders & Lore

Included in the Arcs box is a module called Leaders & Lore, which adds lightly asymmetric abilities to the game. The Leader cards provide you with a powerful strength and a correlating limitation, while the Lore cards give you a rules exception of some kind. Both are drafted during setup, in reverse play order.

The rulebook treats Leaders & Lore as an add-on, something to be experimented with after your first few games. Like many board games with “experienced player” rules, I don’t think you’ll run into any more problems using it on your first play than you would leaving it out. The asymmetries of Leaders & Lore certainly add to the variety of play experiences, and they help to bring out some of the narrative potential in what can otherwise be a very mechanical experience.

What I can’t figure out with Arcs, what will ultimately be decisive in whether or not it joins Root as a personal favorite, is how narratively evocative it is. Does it generate stories in the same way that John Company does? Will I find myself recounting past games in terms of the story that played out rather than in terms of player moves? That’s what I want from a game like this, a rules-heavy experience in which “perfect” play isn’t a possibility.

There are flashes of it, like when I opened a game as the Rebels by sending two of my ships to the far ends of space to quickly establish bases of operations. I could feel the excitement of story in that moment. As the game progresses, though, I experience it very much as I take actions, you take actions, they take actions. It took me many plays of Root to reach the point when games felt like stories, and it required the other players being familiar too. I think Arcs could easily get there. I just don’t know yet.

My feelings on the game are certainly positive. I don’t know if I love it, and I don’t know if I will grow to love it. I keep playing with people who have mixed feelings, often contradictory ones within themselves. “I think my problems with it are also the reasons why I like it,” my friend Boris said during one of our post-game discussions. Having now played Arcs twice, he has walked away both times feeling uncertain. Granted, he’s also the person who keeps texting me to find out when we’re doing the campaign expansion, Blighted Reach. That may be Arcs in a nutshell, right there.

Wanna hear what other members of our team have to say about Arcs?