When I was your age, television was called books

Though I enjoy The Princess Bride for innumerable reasons, one of the simplest is its use of the frame narrative. I do love a good frame narrative—that literary or cinematic device that sets a story within a story. One sunny Chicago morning, Grandpa Columbo shows up to read a fairy tale to an ailing Kevin Arnold. The chosen story of Princess Buttercup and her Westley happens to be one of the most endearing ever told. I mean, come on—Inigo Montoya, Fezzik, Vizzini, Miracle Max, and Humperdinck! Humperdinck! You really can’t go wrong here.

The beauty of this particular frame narrative is the occasional return throughout the swashbuckling romance to the delightfully 1987 bedroom setting. Somehow, the fantastic interruptions of grandfather and grandson make an already heartwarming story even more engaging.

(For what it’s worth, the William Goldman book upon which the movie is based features an even more convoluted and layered depth of frame—especially if you pick up the 30th anniversary edition. Because The Princess Bride stands as one of the most entertaining movies of all time, I find myself advocating the unexpected and unusually backwards position that the book is—somehow—even finer.)

Getting back to the matter at hand: when I play Archmage, I can’t help but think of The Princess Bride.

Inconceivable!

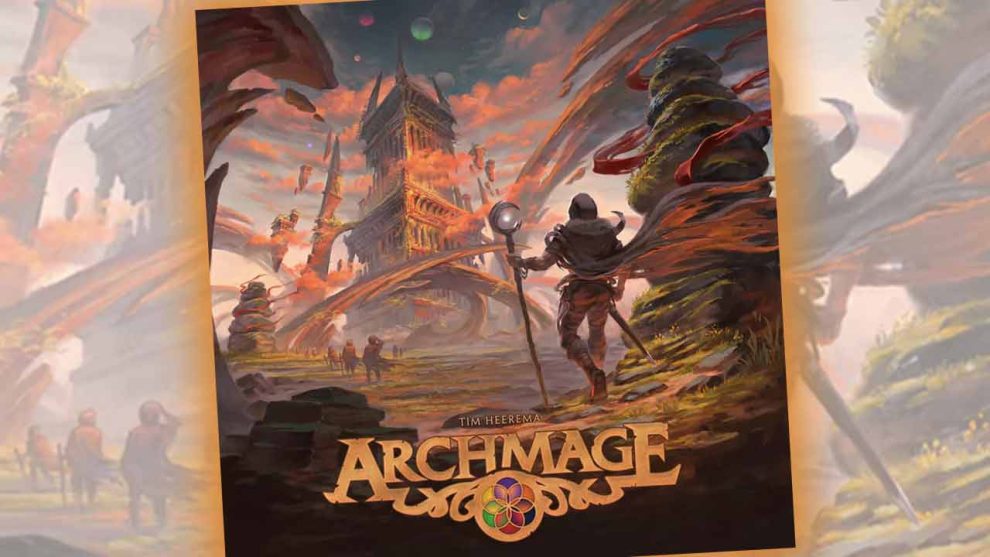

Archmage is the design of Tim Heerema, published under Starling Games (Everdell, King’s Forge). Termed a euro-thematic hybrid, Archmage exists in a world with a heavily-written but not-entirely-consequential backstory. In a world of mythic races and fantastical settings, players assume the role of a Mage vying to fill the vacuum of authority once held by the former Archmage. Over a number of rounds they will scour the land engaging six spheres of magic and train their Apprentices to spread the blanket of their rule in a bid to become the next Archmage.

I know what you’re thinking: What does this have to do with Cliffs of Insanity, Fire Swamps, and Ma-wage? It’s all in the frame story. Let me explain. No, there is too much. Let me sum up.

That dweam within a dweam

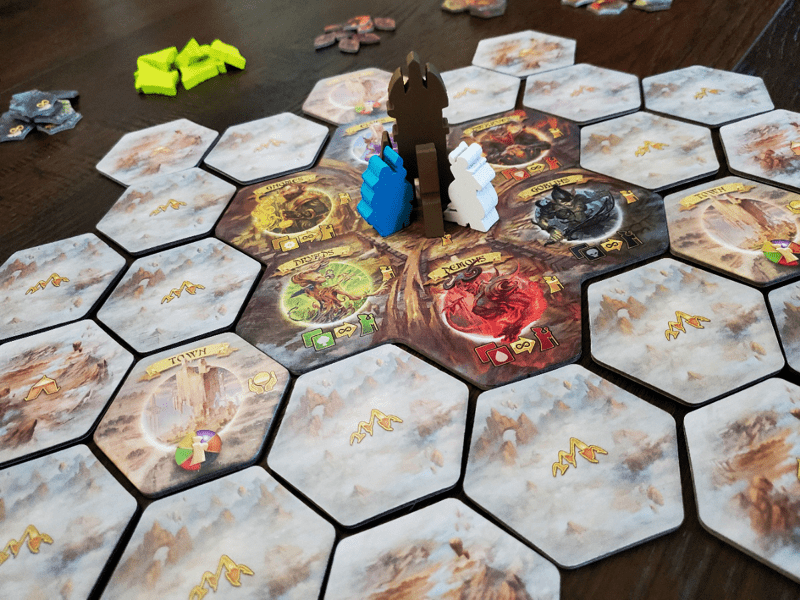

Archmage takes place in two distinct locales. The central board is a conglomeration of hex tiles featuring various locations—Wilderness, Towns, Camps, and Mythic enclaves. These tiles play host to a battle for area control as each Mage moves about the land, revealing and collecting Relics while depositing a trail of Apprentices behind to fend for themselves in support of the cause. At some point, each Mage will construct a Mage Tower on one of the Wilderness tiles—an impenetrable base of operations reminiscent of Tolkien’s Isengard.

The player board is a floor plan inside the magical tower where Mages track the movement of the Planets (game Rounds), their stores of Relics, the development of their Apprentices, and the availability and use of various Spells.

On the one hand, these two locations are obviously in the same world at the same time. And yet, from a game mechanics standpoint, one feels more like a frame story, while the other feels like the fascinating and fantastical center.

You mean you’ll put down your rock and I’ll put down my sword

The central board is laid out based on the player count with most of the hex tiles laid face down. Towns and the central collection of mythic race enclaves remain face up. The center hex holds the Ruined City, which is the starting point for each player’s Mage. Various Spell tokens and Ward tokens are piled around the board for later use.

Each player receives a board, a set of meeples and tokens, and a deck of Spell cards. Six planetary discs matching the colors of the six spheres of magic are laid randomly in the recesses across the top. Based on planetary location, players receive a certain number of each Relic as starting resources.

The center of this board is a series of intertwined rings that create a centralized hierarchy of magical knowledge. Each of the six spheres overlap, creating a network of combinations that allow Mages to blend their knowledge of Relics into more powerful spells. The outer areas are recessed to hold a number of Apprentices. As the Apprentices advance, they step into the folds of the overblown Venn diagram, unleashing combined knowledge. Around the outside of the diagram is a recessed tracker for each sphere of magic where a cube measures the current level (hence the euro-thematic terminology!).

Players keep fifteen Apprentices in their Company, placing the remaining ten in the central supply. Alongside the player board is a Spell Mantle used to track the available and used Spells. Once the pieces are in place, play begins.

And we’ll try to kill each other like civilized people

On each player turn, Mages are granted five Movement points. With each point, players can Move to an adjacent hex, Flip an unexplored hex and gain its resource, or Attack another Mage’s Apprentices. There is no defense in Archmage—expending a single Movement point results in damage and defeat without a Ward (more on that in a moment). Defeated Apprentices are cast back to the supply (though there is a Spell to allow one to return to the Company instead) and blood Relics flow to both parties. If the Mage takes control of the hex tile, an Apprentice may be deployed to establish control.

Based on the Mage’s location after spending all Movement points, one closing action is available. From Wilderness locations, players may build their one and only Mage tower or assign Wards—tokens that add a defense to controlled locations. Wards simply mean two Movement points are required to eliminate an Apprentice instead of one. From Camps players gain three more Apprentices from the supply into their Company. Towns allow players to collect resources from every controlled hex on the board. Mythic and Hybrid race tiles allow players to Initiate Apprentices into their matching magical spheres. These bonus actions make the choice of where to complete Movement quite important.

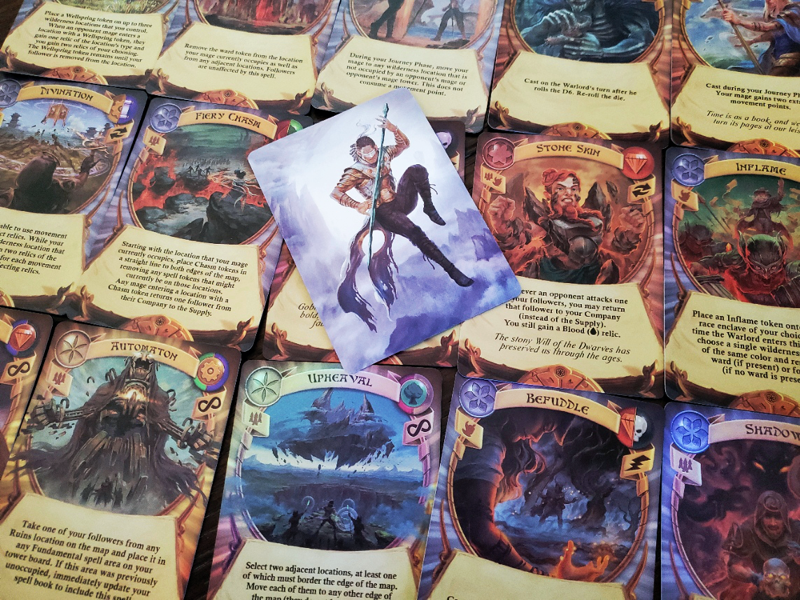

Apprentices are Initiated either by the various races on the map or at the Mage Tower. When an Apprentice is Initiated, its marker is placed on the player board in the appropriate section of the magical Venn diagram. The cost is two Relics of the matching type per Apprentice. This placement grants access to corresponding Spells in the following Round. Spells are cast by spending the same Relics to enact the effect.

When a player finishes on the hex with their Mage tower, in addition to Initiating one Apprentice, they may Promote Apprentices through the diagram by having two adjacent Apprentices “face off” for the right to move on. One Apprentice moves up, while the other is removed altogether back to the Company. Thus magical development comes at a sacrificial cost, as two lower level Spells might be lost in attaining the one greater Spell. For this reason, Initiating Apprentices is relatively constant during the game, both for Spell access and endgame points.

Spells accomplish the sorts of things you might expect. At the Fundamental level, they grant extra Movement points, allow for the exchange of Relics, and the ability to junk other players’ Relics. The Advanced Spells introduce tokens to the board that grant bonus Relics, restrict movement, or enact nasty effects during attacks. Master Spells amplify the magical goodness to eleven. The escalation of effects comes with an escalation of cost, which is always one Relic for each magical sphere included in the Spell. Spells definitely ratchet up the combinations and depth of each turn.

In between Rounds, players update their Spell book according to the Apprentices’ locations, tend to any lingering Spell tokens on the board, and advance one of their planetary markers toward the center. Each movement in the heavens grants a boon of one Relic matching the mobilized planet. Once the planets align in the center, the New Age begins and the game ends.

You’re trying to kidnap what I’ve rightfully stolen

I can hear you asking: from whence do my points arise?

Points in Archmage are split between the land and the magical Venn diagram. In the diagram there are three levels of available Spells. Apprentices in the Fundamental, Advanced, and Master levels earn one, two, and four points respectively. On the land, each of the game’s Wilderness tile types grants a score of two points to the Mage who controls the majorityin the category. Ties earn a single point. Losses earn none.

Overall, there is a greater potential for points in the Venn diagram, but the ten area control points are important enough that the map cannot be ignored. More than twenty points is a solid day here.

It’s not that bad

There is an unmistakable three-fold progression to Archmage. Early on, there is a push to explore the map, loot the first Relics, and establish a Mage tower with some semblance of a guarded community across the land. The middle phase involves moving about and maximizing timely stops in the Town to gather Relics for Initiation and Promotion of Apprentices. The late phase features the utilization of the Spells in a battle over the variety of Wilderness spaces on the map. The progression is not scripted per se, but there is no mistaking the emphasis in each leg of the adventure.

It is this three-fold progression that gets me thinking about The Princess Bride and its seamless use of frame narrative and tasty center. Archmage has a delicious core in the magical Venn diagram. Based on the initial gift of Relics and the resources unearthed in that first leg of exploration, players are unleashed to develop a useful and strategic combination of Spells that suit their evolving capacity for Relics.

But the gateway to the juicy middle is the hex map. In order to effectively use the diagram, the first three to five turns must include effective exploration. Not only that, but the established diagram must then become the vehicle of exertion on the map to settle the matter of area control. In some ways, it feels like two different games altogether—one spanning the beginning and end with another in the middle.

I can get behind that—provided the theme supports and holds the divergence together.

The rulebook of Archmage opens with five full pages of world-building. Why planets? Why the spheres? Why these mythic races? Why these Relics? While pages like this often serve to make the game far more intimidating than it needs to be, I appreciate the depth Tim Heerema has invested in his backstory. I glanced at them before the game, then revisited them in greater depth after seeing the mechanics in motion. They work… if you’re into that sort of thing.

Just as Grandpa Columbo and Kevin Arnold repeatedly peek and speak into the fantastic center of The Princess Bride so that you never forget them, the map is always calling in Archmage. There is always something brewing for the brutal push of the last few rounds when the area control reaches its fever pitch. Apprentices fall, or worse yet they are Imprisoned or Corrupted. Wards fall as Mages set out to tread new ground for their Company. The Spells are the lifeblood of the system, but the frame is ever-present, dangling those ten points like some magical carrot.

As you wish

Throughout the movie, the reluctant Kevin Arnold is worn down by the charm of Buttercup and Westley to the point that he asks Grandpa to come the next day to read it again. The closing frame casts the judgment on the whole and you expect that they’ll be just as animated in the next telling.

I believe the same holds true for Archmage. The slow start of exploration will elicit sounds like those of a sick and whiny nine-year-old as the Relics gradually build and the land takes shape. The central Spell-casting will undoubtedly awaken a sense of excitement and adventure as Time and Matter, Blood and Death yield their powers to the capable Mage. If that sense is strong enough, the final verdict might just be that the area control finale warrants visiting the experience again tomorrow, next week, or right away.

The Venn diagram is quite fascinating on its own. But no matter how many feel-goods flow from those interlocking rings, I have a feeling folks will love or hate the game based on the interactions of the map. Either you will enjoy the partitioned nature of the game arc—the frame and the core—or you’ll swear it off forever. Personally, I dig it. My teenage son loves it, and I’m more than happy to tell and retell this fantasy story together while the magic lasts.

Add Comment