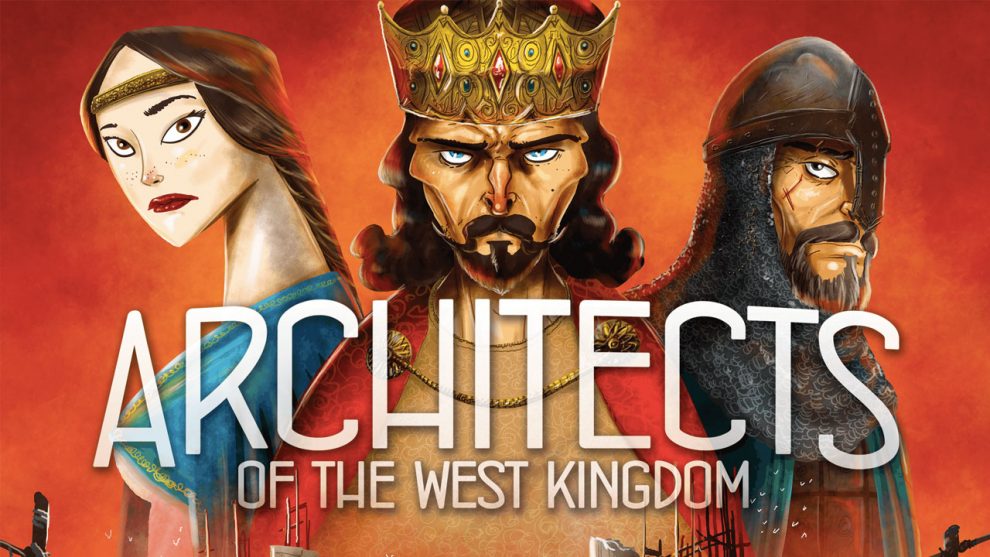

Set in the waning days of the Carolingian Empire, Architects of the West Kingdom has players take on the role of royal architects jockeying for favor and renown. Your workers collect resources, hire apprentices, and construct buildings, including the King’s magnificent new cathedral. Throughout the game, the actions you take will affect your virtue; do you remain honest and aboveboard, working on the cathedral while paying your taxes and more easily managing debts, or do you take advantage of the temptations to be found in the Black Market, easily accumulating scarce resources while running your reputation into the ground? In Architects, the choice is yours.

Why Do We Build the Wall

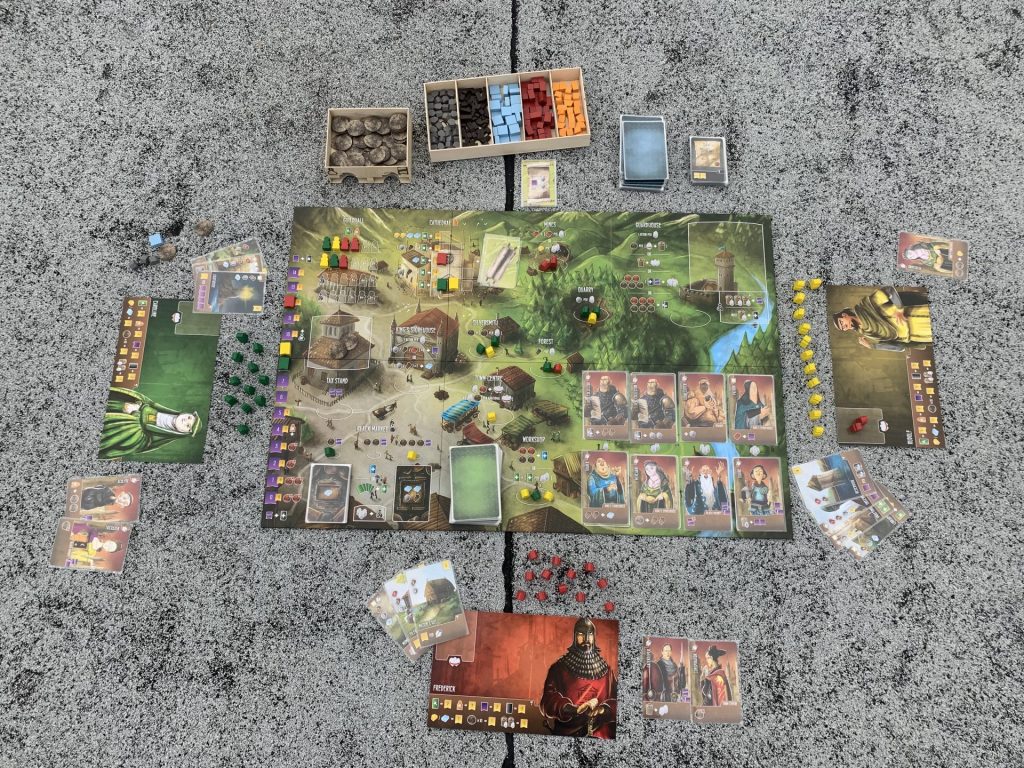

Architects of the West Kingdom is a worker placement game in which players take turns sending one of their twenty identical employees to any of the dozen or so locations in town. Short on money? Send Aled—I like to name them—to the Silversmith. Need some stone? Jacinth can run to the Quarry. You’ll use the materials you collect to build landmarks and contribute to construction on the King’s cathedral, reaping any short- or long-term benefits associated with your work.

Any time a player wants to build, they send a worker to the Guild Hall, where they will stay for the rest of the game. If building a Landmark from your hand, you pay the appropriate resources and play the card to your play area, claiming any immediate bonus it may give. If you’re contributing to the cathedral, you pay the cost associated with the next tier of the cathedral track and move your marker up a row. Each tier is worth an increasing number of points and has a limited number of spaces available. Players are unable to work on the cathedral if the next row is entirely full, and the final tier only has room for one. Competition for those 20 points can be fierce.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes, Pt. 1

This is all standard-issue as far as worker placement games go, but Architects distinguishes itself with several tweaks to the formula. Worker placement often limits each action space to a single meeple and uses a round structure where players clear their workers off the board every few turns. In Architects, you cannot block other players in the majority of locations, and workers stay where they are until forcibly removed. This is to your advantage, since more of your own workers in one location means more benefits for you. If you send Morgan to join Jacinth at the Quarry, you’ll get two stone on that turn.

Given that workers stay out on the board, it’s inevitable that you will run low if not out. Whether you need your own workers back or someone else has more presence in one location than you’d like, you can use the Town Center to round people up. Your own employees are returned to your supply, ready to get back to work, and you hold your rivals’ underlings captive. The world of Architects is an unscrupulous one, and you can throw all sorts of slanderous accusations at your opponents’ business practices. When you turn them in at the local Garrison a few turns later, they’ll be held on accusations of impropriety while you collect a bounty of one coin per head. If your own workers have been accused of wrongdoing, you can secure their release, no questions asked.

Friends Friends Friends I Definitely Have Friends

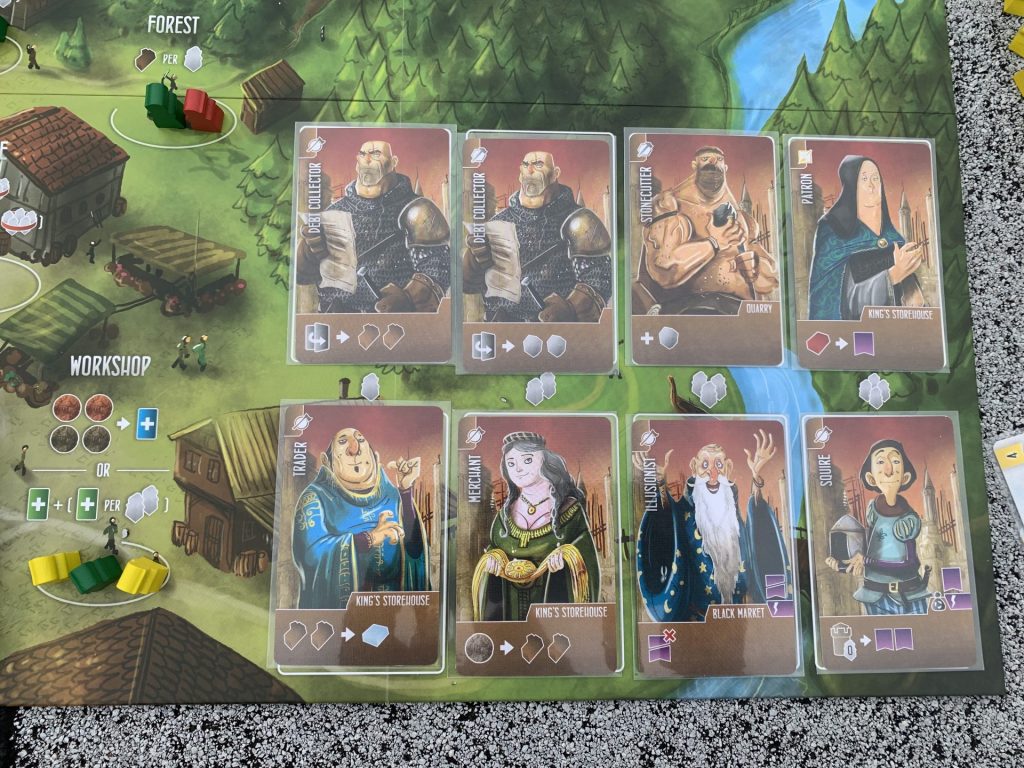

The apprentices are the common thread woven through all three West Kingdom games. At the workshop you can recruit one of eight available apprentice cards that grant you ongoing abilities and allow you to build certain kinds of landmarks. These abilities can vary wildly, encompassing everything from material bonuses to extra actions available only to you. Each apprentice on their own can suggest a path to victory, and finding combinations that work well together is where the game shines. The apprentice deck that comes with the game is generous—let alone if you get all the mini expansions like I have—and helps introduce a significant amount of variety to subsequent plays.

A quick note on that: the Age of Artisans expansion introduces a setup step where players, in reverse turn order, claim one of the available apprentices from the workshop before beginning the game. The designer, Shem Phillips, has said in interviews that he regrets not including that rule in the base game, and even though I don’t have Artisans, I do use that variant.

You Wanna Buy a Sundial?

The Black Market, a collection of three spaces in the lower left quadrant of the board, offers easy access to a selection of otherwise expensive actions and rare goods. Instead of paying four coins to hire an apprentice with two of those going towards taxes, why not pay two under the table and hire any apprentice you want? Why spend two turns sending workers to the mine to get one lousy piece of gold the “honest way,” whatever that means, when you could pay three coins to snatch up two bars now, and we’ll throw in some wood and a stone while you’re here?

Workers in the Black Market stay there until all three spaces are filled, triggering a Black Market Reset. All workers in the Black Market are rounded up and sent to the Garrison, and any player with three or more workers in jail loses a virtue. Additionally, the player with the most workers in prison takes a debt, which subtracts two points if unpaid at game’s end but rewards one virtue if paid off. The goods in the Black Market are swapped out for new offerings, and the three spaces are again available.

Be warned that the goods here come at more than just a monetary cost. To the left side of the board sits the Virtue track, which follows your reputation throughout the game. Working on the cathedral increases your virtue, while taking advantage of the wares on offer in the black market reduces it. There’s a balancing act here. The Black Market is the easiest place to get the rare materials you need to work on the cathedral, but you can’t shop there if your reputation is too high, which means it will take longer to progress up the cathedral than it would if you were a little disreputable. On the other hand, if your reputation is too low you cannot work on the cathedral, the best method for increasing your reputation. Do either too much, and the other will slip out of reach. The Virtue track encourages players to engage with a variety of strategies over the course of the game, but more than that, it gives Architects of the West Kingdom a wonderful and pervasive feeling of narrative.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes, Pt. 2

The aggregate effect of all these tweaks is a worker placement game where you have to pay just a little bit more attention to what everyone else is doing. You are not only trying to gauge when to build, or when it’s safe to go to the black market, or when you should go out of your way to free your workers from prison, but you also have to keep track of what apprentices your opponents have hired and the action spaces that will benefit them as a result. Repeatedly going out of your way to obstruct others is not going to win a game of Architects, but doing it just enough to keep your opponents from running away with it is necessary.

Miscellanea

The choice to make spaces both unblockable and infinitely reusable is a fascinating one. It eliminates two of worker placement’s keystone tensions. Player interaction in the genre typically revolves around blocking your opponents or having to think on your feet as a result of losing a space you needed. The most unforgiving worker placement games—I’m thinking specifically of Russian Railroads—offer such a paucity of spaces that every move is a knife to someone’s heart. The more congenial titles, like Viticulture, give you a special worker who cannot be blocked or an action space that lets you copy any other space on the board. With those games much of the tension comes from figuring out just when to use that safety net.

Architects finds surface tension in timing when you want to build, when you want to trigger a Black Market reset, and when you should stop one of your opponents from getting too many workers at a given space. The core tension is in choreographing your movements on the Cathedral and Virtue tracks.

Conclusion

Accessible but with subtle complexities that will reward more experienced players, interactive without ever being punishing or overly confrontational, and richly evocative of a world through both its art and its mechanisms, Architects of the West Kingdom is a terrific game. It is a tremendous amount of content for such a small box and it is a great choice for introducing people new to The Hobby™ to middle-weight designs.

I should note that Architects includes a very good solo player mode, one that manages to capture much of the feeling of playing against a human opponent. The AI bot can also be used to add a third opponent to a two-player game, which I highly recommend. This board thrives on just a little bit of chaos.

Finally, the West Kingdom series is a great place to start if you are looking to transition people into heavier titles. The iconography in Architects carries forward into Paladins of the West Kingdom and Viscounts of the West Kingdom, two considerably heavier—and, I would say, considerably better—titles. Having the reference point of familiar symbols can make downloading a bigger game much easier for people used to lighter fare.