Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I’m staring at five animal cards. All I have to do is split four of the cards into two piles face up on the table and hand my opponent, Lisa, the fifth. She’ll add it to one of the piles, choose a pile to keep and give me the other pile.

I’ll get points for keeping my ninja monkey agent and if Lisa takes my dastardly octopus spy. We both want to get the spymaster owl – this game’s double agent. I think the femme fatale fox is Lisa’s agent (which she’ll want), and there’s a suave lion in a tux that might be Lisa’s spy, so I should avoid that. But… I could be wrong about Lisa’s agent and spy, either could be the gadget-whizz chameleon which isn’t amongst the cards in my hand.

How should I split the cards so that Lisa chooses to give me what I want? And which card should be the fifth card?

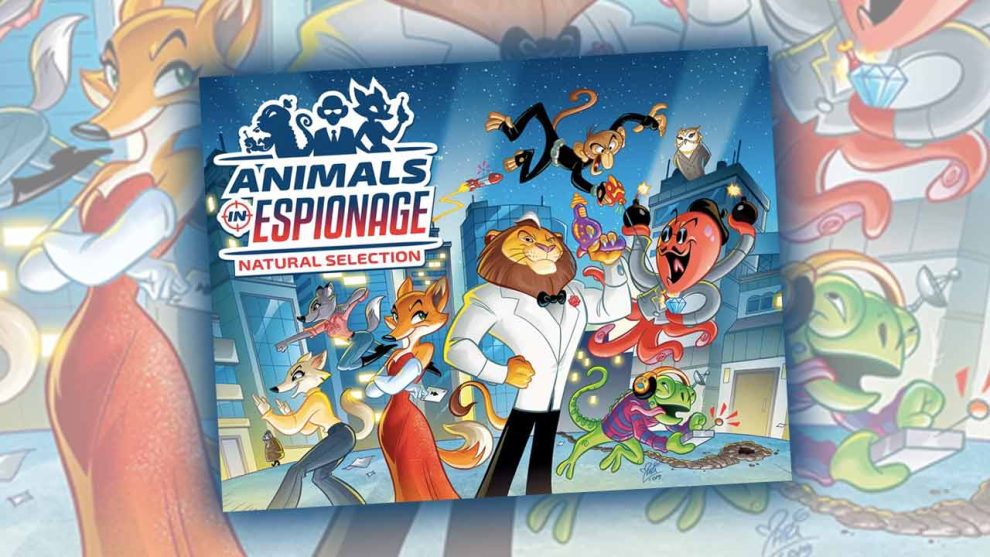

Animals in Espionage

Inspired by the ‘Fact of Fiction’ card in Magic: The Gathering, Animals in Espionage leans into the ‘I split, you choose’ game mechanism hard. At the start of the game you know the identity of three of the six animals in play: your agent, your spy and the double agent. The identities of the remaining three animals start off a mystery. Two of them will be your opponent’s agent and spy, the third won’t be involved in the game at all.

Over the game’s six turns you begin to piece together an idea of those unknowns. Perhaps your opponent is snaffling up foxes or trying to force lions upon you. If they’ve just chosen a stack of chameleon cards, that might mean that their agent is the chameleon. Or it might mean that their spy is in the pile of cards that came your way.

After the final turn you gamble on your gut, wagering a few points on which animal you think is your opponent’s agent. Generally, you’ll have a good idea but if you aren’t completely certain then you can bet fewer points. When both players are playing well the difference between wagering 1 point and 3 points is the difference between winning and losing.

At the end you tot up all the points from collecting your agent and the double agent, from the end of game wager, and from any of your spy cards that your opponent picked up. Most points wins.

Life of (s)Pi

I really enjoy the ‘I split, you choose’ mechanism in games. It’s so wonderfully personal and interactive, forcing you to get into your opponent’s head and view the game from their perspective. Chuck in a little hidden information and suddenly there are wheels within wheels, every decision meaning something. Why did they take that pile and not that one? Why did they divide the piles that way? Which pile do they want me to take and why did they smile to themselves when I chose the other pile?

Animals in Espionage adds a novel dynamic with the fifth card, prompting additional thrusts and parries – which of the piles to keep and whether to keep or give the fifth card. It can be very effective in uncovering those unknown identities, letting you ask more direct questions. If I think your agent is the fox and I feed you this 1-point fox as the fifth card, will you prove me right by keeping her? Or will you give her back to me and if so, is the fox your spy or a furry red herring or perhaps you think she’s my spy and the fox isn’t in this game at all. Successfully navigating the Escher-logic of Animals in Espionage is deeply satisfying.

There’s a lot to like about Animals in Espionage, if you ignore the slightly awkward title. It takes a turn or two before the different identities click into place but once you get into the flow of things it’s such a breezy experience. The box says 15 minutes but you could take off the wrapping, learn, teach and play your first game in that time. In fact, if you take more than 10 minutes for a game (which is well over 1 minute per turn), the chances are that the game’s momentum is twitching on the floor, foaming from a cyanide capsule.

Once you’re happy with the base game, the included Mole variant is well worth trying. Neither player wants the mole cards, creating an anti-double agent and adding another force to the push-pull of every decision. Where you might bait a pile with a double agent, you can deter your opponent with the mole or neutralise cards you know they want. What’s more, the variant introduces a facedown card that the chooser never sees, perfect for hiding both good and bad cards from your opponent. It’s a lovely tweak to the original game, adding bonus mind games for both splitter and chooser.

Animals in Espionage’s artwork is joyous, full of energy and humour. Even now I’m looking over at the box lid beside me and smiling. Each animal has cards worth 1, 2 and 3 points, with the exploits of the animal getting crazier as the worth increases. The lowest lion has a martini, the highest lion a jetpack. The owl is a particular favourite, her final power pose is just magnificent.

It almost makes up for the fox, one of the two identifiably female characters in the game, who ropes in additional foxes with her increasing value, à la Charlie’s Angels (or even Fox Force Five). The reference is nice but why does the male lion get a jetpack and the male octopus get a ray gun whilst the female fox just gets helpers? Is she not strong or competent enough by herself? And why is the fox’s picture just copied and pasted from value to value when the other animals have different artwork for different values? It’s a weird misstep amidst artistic excellence.

Along Came a Spy-der

At its best, Animals in Espionage prompts all the questions I asked earlier. These are juicy questions, occasionally rich, occasionally silly, but always rewarding when clever moves are made and puzzle pieces fall into place. And, by and large, they will. About 80% of the time you’ll guess your opponent’s agent correctly at the end. This isn’t a problem, the trick is in how early you can put the clues together and then be able to act upon what you’ve worked out.

It’s here where the false moustache slips slightly.

When I first started playing Animals in Espionage I loved how loose it felt. It’s an uncommon experience in a genre where every turn counts and every decision means something. Take the minimalist zero-sum duel Hanamikoji and its sequel Geisha’s Road, games where a single mistake costs you everything. Or there’s the seemingly gentle Tussie Mussie where each of your four final cards (and hence decisions) needs to count.

In Animals in Espionage mis-steps aren’t as costly. You’ll end the game with around 15 cards, plenty of which are likely to be spies (your opponent’s and your own) representing failed defences and missed opportunities. It’s a forgiving game and it feels more relaxed as a result. You can enjoy the decisions and interaction without worrying about your heart rate.

But, viewed in another light this looseness is also flabbiness.

You need the right tools to piece together the hidden information in the game, and then you need the right tools to try and make the most of that knowledge.

But often the deck of cards and the fog of hidden identities gets in the way. You can end up staring at a hand of cards that just aren’t interesting, useful or especially fun to play. At the start of the game you could be presented with a choice between two piles of cards you know nothing about. You might as well just flip a coin and hope. Towards the end of the game you might be certain of your opponent’s identities but not have the cards to do anything about it.

It’s a problem that’s accentuated in the second included variant in which players only discover the identity of the double agent by collecting walrus cards during the game. In theory it’s great, another centre of gravity tugging at player decisions, asking if you want to sacrifice points for knowledge.

But in reality it’s unusual to collect enough walruses until at least half way through the game by which time it might be too late. In one game Lisa discovered the double agent identity and immediately swore. Seconds before she had gifted me the bulk of that animal’s points in what, with the information available at the time, had appeared to be the optimal move.

Aye-aye I Spy

Perhaps this is mountains out of molehills. In half an hour you can get Animals in Espionage off the shelf, play three games and return the box to the shelf. During that time you’ll have probably laughed, smiled and groaned. You’ll have also felt sneaky at least once, savouring that warm feeling that comes from outwitting your opponent. That Animals in Espionage can make you feel all that in such a short amount of time is to be applauded. Does it matter that you’ll also be stymied by the deal once or twice, that occasionally you’ll feel powerless and, consequently, uninterested?

It turns out I’m split on Animals in Espionage, but choose for yourself whether it sounds like something you’d enjoy.

Add Comment