Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Any time I get the chance to play yet another one-shot murder mystery / escape room game, I am down!

During our meetings with dV Giochi / DV Games at SPIEL 2023, I had the chance to chat with Barbara, our contact with the publisher. While our conversation was brief, we talked about my coverage of some other one-shot mystery games that hit the sweet spot for me. These include the Exit: The Game series, Unsolved Case Files, the Cold Case series, the Suspects games and a few other titles.

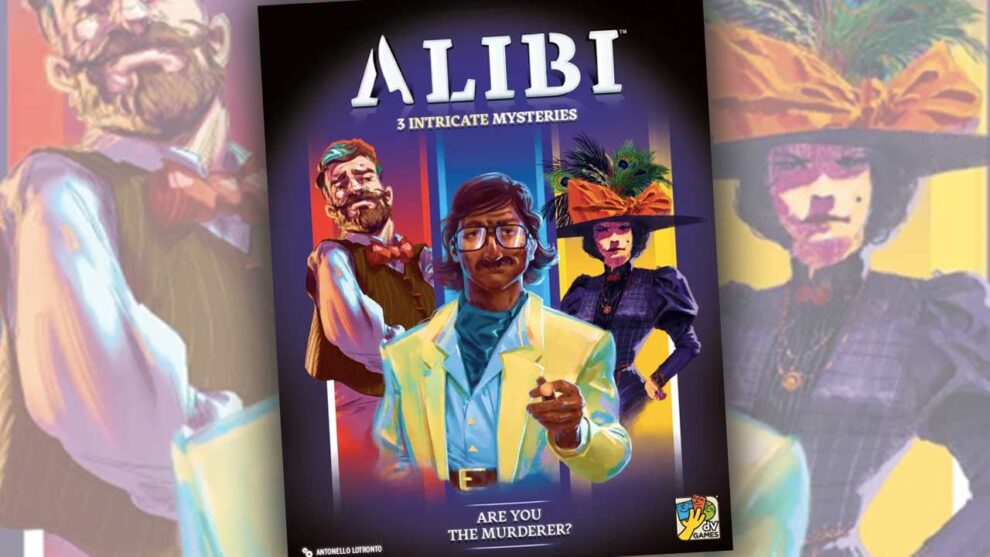

Barbara listened as I spoke about my bonafides, and our conversation ended with a review copy of the new mystery game Alibi. Alibi is an interesting package: it includes three one-shot cases that each take about an hour to play. Each player takes on the role of a suspect in a murder case and is given a very small deck of cards with their character story and background during setup.

Alibi is essentially a five-player-only game, with a six-player variant where one person takes on the persona of a detective who seems a bit like Hercule Poirot, the hero from the Agatha Christie mystery novels.

Like a good dinner party murder mystery game, no one knows if they are the murderer or not until after the very last round.

No Spoilers, Yes Table Talk

There are three mysteries in the box, and if anything, the “worst” part of Alibi is how generic each of the cases sounds: Murder on the Nile, A Dish to Die For, and Blood on the Tartan. For this review, I played Murder on the Nile (at six players) and Blood on the Tartan, using a four-player variant where one of the innocent characters is scripted using PDF files found on the DV Games website.

The game system for Alibi is always the same. During setup, each non-detective player is given a deck with a backstory of their character, and five statement cards that provide color for that character, slowly doled out with one statement card per round so that no one is overwhelmed with a massive amount of worldbuilding before they really need it.

Each of those statement cards also has a secret listed at the bottom of the card.

A round begins with one player reading at least one of their statements aloud to the table. This player is picked based on whether there’s a large star printed in the upper corner of their round card. This is only meant to start a discussion, though. Alibi wants to be a game that encourages free-flow conversation, to let the facts bubble up naturally and with flavor. For those still missing their time on the drama team or belonging to a high school theater club, Alibi helps scratch the itch!

This discussion allows for suspects to question each other, or for the detective to ask probing questions of each suspect. It only takes about 10 minutes to ensure that all the statement data gets to the other players at the table. If a suspect is ever asked directly about a specific point that is the named secret on their card, that character reveals their secret.

This may or may not force Clue cards to be played to the center of the table. Usually, Clue cards provide more flavor to the evidence that is being discussed by the suspects, such as pictures of murder weapons or key items that should be inspected for details.

After all the character statements have been relayed, players place their round card face down in front of them, and a new round begins. After five rounds, each player secretly looks at a sixth card from their deck—and discovers if they are the murderer or not.

The game briefly pauses at this point. One by one, each person will give their alibi to prove their innocence (or disguise their guilt). In my plays, we gave each person about a minute to wax poetic. Once this stage is complete, all players will shake their fists Rock-Paper-Scissors style and end by pointing a finger at the person they think is the murderer.

Anyone who correctly picks the murderer wins. The murderer can win if no one picks them or if they have been picked less than another innocent player.

Theatrics

The deduction/logic/clue system of Alibi was a miss during our plays. A good listener may be able to suss out whodunit, but ultimately I thought that was the weakest part of the game. In one case we played, I’m not sure I heard anything that would have specifically pointed towards one suspect during our game. This led to lots of, “There’s NO way we could have known it was ______!” from the players at the table.

I liked Alibi most as an opportunity to do some acting with friends at the table. Alibi hinges on the table talk during each round, and in this way—assuming you’ve got the group to act out a script over a 60-minute running time—Alibi was a great time at the table.

I’ll give you a few examples, without spoiling anything specific. During a round of the first case, Murder on the Nile, it’s clear that something was a little fishy between one of the characters and one of the people murdered. But the way each character reacted to this news, by getting into character and leaning in on the humor of the situation, was comedic gold.

Even better than this, some statements that came out in rounds one and two led to running jokes about things characters said, clues about a murder weapon, the profession of one of the suspects…I mean, I don’t even have actors or comedians in my game groups, but if you’ve got a team of five friends who are looking for a good time, the first 55 minutes of a game of Alibi are really, really rich.

But, at the end of the case, when we have to find out who really committed the murder? I’m not so sold on that part. Multiple players complained that getting to the facts was quite difficult in Alibi. A testament to this came during the end of a case when we pointed fingers at four different people out of a five-person suspect pool.

NOBODY had any idea on who really committed the final crime here.

I don’t do a lot of dinner party murder mysteries, so I can’t really compare this to games like that. I do know, however, that those can be longer games. Alibi is pretty compact, and my two games took an hour for the first one, then 50 minutes for my four-player game. It’s tight and doesn’t overstay its welcome.

If you have the group for it, Alibi is fun as a silly group activity, but not a very strong logic puzzle for fans of deduction games. And each of the three cases is definitely a one-shot deal with one guilty suspect pre-determined before you open the box. Give Alibi to a friend after you wrap it up, and the value proposition lasts a little longer!

Back in the day, I played a few of the “How to Host a Murder” party games. If memory serves, I played four of those and a Star Trek “How to Host a Mystery” game (a re-branded version because you cannot have a member of the main cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation be a murderer). Those were fun, and even people I knew that never seemed like the drama-club type would get into costume and character and ham it up! Good times all around.

But the basic format of this game is very. very similar to the format of those games, and the final result is, unfortunately, much the same. You can be in the midst of this sort of thing, listen carefully to everything being said, and in the end, have eight fingers pointing at eight different people because there was just no real way to deduce out who did this. Hell, in the Star Trek “How to Host a Mystery” game, everyone playing was sure that they were the one who did it. Only one of them was right, of course.

This sort of game is a great idea. On paper.

In practice, the game play of the early and mid-game is much, much better than the end-game. I have yet to find a version of this kind of game that can /nail the landing/, as it were. Oh well.

Thanks for a great review.

Thanks, David!