Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Aldebaran Duel is a two-player game where two opponents face off as leaders of space fleets vying for control over a newly available planetary system. Over three epochs, the players will discover new planets, populate them, use their mineral wealth to build spaceships, and try to gain superiority over their opponent.

A Race For the Galaxy

In the game, the players use multi-use cards to purchase other cards from a card offering (by discarding cards from their hand) in order to increase their movement along several technology tracks—many of which will help reduce the cost of future cards. At the end of each epoch, an interim scoring will be performed to determine who has the greatest military might, and also who has mastered the art of trade and diplomacy. These criteria will move a marker around a grid on a shared board. Where the marker ends its movement determines who receives victory points, as well as how many.

At the end of the third epoch, players will do a final scoring. In addition to the points received from the trade/military/diplomacy scoring, players will earn points based on how well they moved along the various resource tracks (as well as from a couple of other sources). And, when the cosmic dust settles, the player with the most points will be declared the victor.

Of course, this is a very high-level overview of the game. If you think you’ve heard enough and just want to know what I think, feel free to skip ahead to the Thoughts section. Otherwise, read on as we learn how to play Aldebaran Duel.

Intergalactic Planetary…

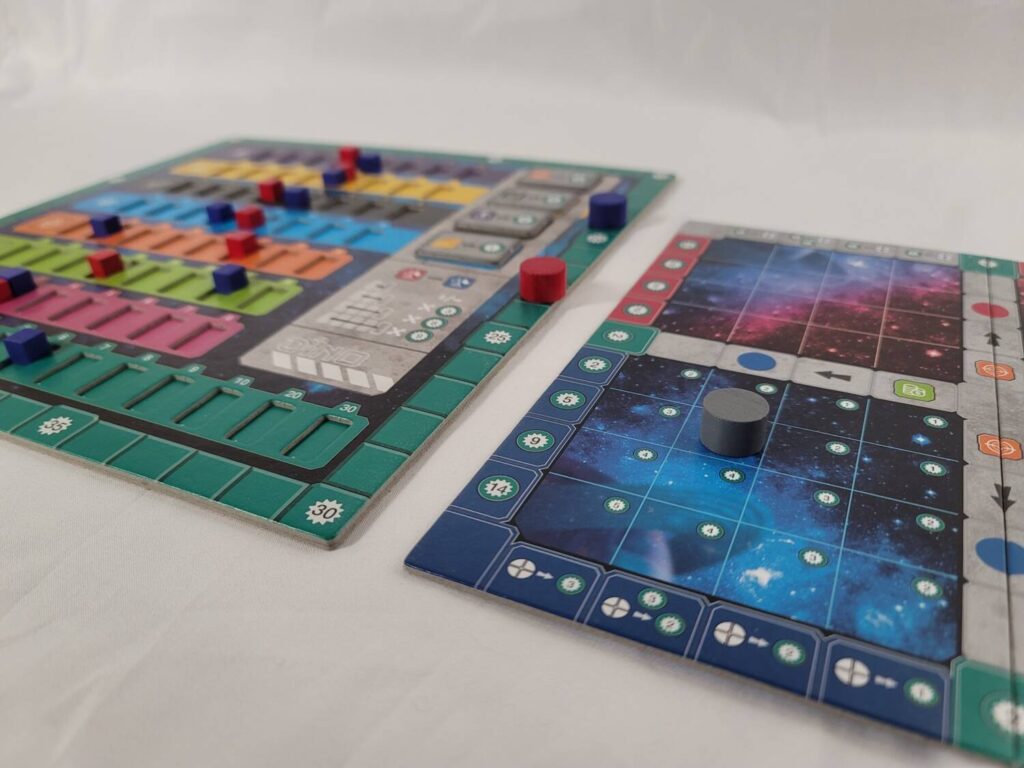

A game of Aldebaran Duel is set up thusly:

The Main board and the Board of Influence are placed in between the players. Each player chooses a color and receives the markers and cylinders of their chosen color along with five randomly chosen Science cards. The game recommends that the players draft these cards, but there’s no reason they can’t be randomly distributed.

The players place one of their markers onto the starting spaces of each of the tracks on the Main board. Their cylinders are placed onto the starting space of the scoring track. There is also a neutral cylinder which is placed into the center of the Board of Influence. Three Scoring tiles are chosen at random and placed on the marked spaces at the end of each of the top four tracks on the Main board.

Next, the Epoch cards are divided into decks based on their epoch number. These are shuffled and placed face down. Then, form a two by three grid with cards drawn face up from the Epoch 1 deck (the ‘offer’ in the game’s vernacular). The Wildcard Resource and Space Object tokens are kept off to the side in a general supply. Then, choose a starting player and you’re ready to begin playing Aldebaran Duel.

…Planetary Intergalactic

Aldebaran Duel is played over the course of three epochs, with an epoch ending once both players have passed. During the epoch, players alternate turns and, on their turns, they can either take cards from the offer, play a card from their hand, or pass.

When taking cards, each player can choose cards whose combined total does not exceed three. Cards in the top row cost three. Cards in the middle cost two. The bottom row costs one. So, a player can choose a single card from the top row, or a single card from the middle, or a single card from the middle and a card from the bottom row, or a single card from the bottom row, or two cards from the bottom row. After taking cards, the remaining cards in each column slide down, and new cards are drawn from the deck to replace them.

Having read the previous paragraph, you might be wondering why anyone would ever choose just one card when they could be choosing two. There are a couple of reasons. Firstly, there is a strict hand limit of seven cards. If taking a card would cause you to exceed seven cards, you can’t take any cards. Secondly, there may be a strategic reason for the decision. Perhaps there’s a card you really want at the top of the left column and you don’t want your opponent taking it. Keeping it at the top of that column makes it cost prohibitive and, if your opponent doesn’t take it, chances are they’ll take one of the cards beneath it, thereby making it cheaper for you when it comes back around to your turn.

Playing cards is a bit more complex. Each card in the game is unique, but every card has certain things in common with every other card. First, at the top left of each card is the cost associated with playing the card from your hand into your playing area (along with any prerequisites for playing it). These costs are always some combination of resource symbols. These resources can come from one of three places: your resource production tracks, by discarding Wildcard Resource tokens, or (more commonly) by discarding other cards from your hand. This brings us to the second thing that all cards have in common.

At the bottom left of every card is a symbol (or symbols) that depict which resources the card can be discarded for. So, if a card calls for two Food resources and you’ve only got one Food resource production, you can discard a different card with a Food symbol on it to pay for the second Food. Or, you can discard any two cards to cover for the Food resource. Regardless, once you’ve paid the cost, the card enters play. Of the cards, there are several types:

Production Stations raise one of the levels of your resource production tracks.

Space Shuttles raise the levels of your military, trade, and diplomacy tracks.

Planets produce bonuses once they’re fully colonized. Each planet is divided into quadrants. Some of these will be blank. These blanks are filled in with Colonization cards. These provide bonuses as soon as they are played to a Planet.

Colonization Ships have powerful effects that are triggered once they have been added to a fully colonized planet.

Additionally, some cards you play may have Space Object icons printed on them. Some cards, when played, will cause Space Object tokens to be produced. These tokens are worth a variable number of points at the end of the game based on how many matching icons you have across all the cards you’ve played over the course of the game.

A Star is Born

At the end of each epoch, an intermittent scoring is performed. The players compare their positions on each of the military, trade, and diplomacy tracks (in that order). The grey marker moves a number of spaces equal to the difference between the player’s total with the highest amount on a given track and however much the other person is scoring. So, if the highest player is at a 3 and the other person is at a 1, then the grey disk would move a total of two.

The direction the disk moves is dependent on the track being assessed. The military track moves the disk vertically. The trade track moves the disk horizontally. The diplomacy track puts the direction of the movement in the player’s hands. Where the disk ends up determines how many points/bonuses are awarded and who receives them. It is also worth mentioning that this disk does not reset in between epochs, and the further it gets pushed into a player’s zone, the greater the rewards will be for that player. Players also earn points generated by their Permanent Point Production tracks.

After this “evaluation of dominance in the universe” (as the game calls it), players will have a chance to play one of the Science cards from their hands, if possible. These cards will provide immediate effects, ongoing effects, or end-of-game bonuses.

End-of-game points are also awarded from the Scoring tokens at the end of each of the resource tracks (based on who has dominance on them), points from Space Object tokens, and two points for each fully colonized planet.

Thoughts

Ten or so years ago, I was introduced to the game Keyflower for the very first time. In that game, you’re using the meeples hidden behind your screen to bid for tiles from a central display in order to add them to your village to increase your productivity and earn points. The tricky part of it is that the workforce you need to produce things is the very same workforce you’re having to use to bid for things. It’s a game that forces you to decide how much you’re willing to sacrifice for sometimes seemingly insignificant gains.

It was the first time I’d ever been exposed to this sort of thing in a board game.

That sacrifice mechanic (for lack of a better term) really spoke to me. In fact, it quickly became one of my favorite board game mechanics overall. It’s an easy way to lend depth to a game without increasing the overall complexity. I’m also a fan of Vladimir Suchý. So, when I heard he was coming out with a two-player game featuring one of my favorite game mechanics, my curiosity was instantly piqued.

Getting my hands on a copy of it wasn’t easy, but I’m pleased to be able to say that I own Aldebaran Duel now. And, I’m even more pleased to be able to tell you that it was well worth the wait.

Aldebaran Duel is a fantastic game.

My only real beef with it is in the way that Space Object scoring is handled at the end of the game. Each token’s value is dependent on how many of the matching Space Object icons the player has across all of their cards. For instance, if you’ve collected two of the red Space Object tokens and have only two red Space Object symbols across all your cards, they’re only worth two points apiece. Whereas they’d be worth three points each if you had three or four symbols across all your cards. However, each different colored Space Object has a different set of criteria that define how those tokens score. There’s a handy chart provided in the middle of the rule book so that you don’t have to memorize all of this.

And therein lies the rub. It seems like this kind of thing would be a prime candidate for a Player Aid or, at the very least, being printed on the back of the rule book where it can be easily found. Yet, this is not the case. While it’s not a deal-breaker, it sure is frustrating.

Aside from that, everything else is great.

In Aldebaran Duel, Suchý uses multi-use cards to great effect. There are very few easy decisions in the game. The tough choices begin from your very first turn. As the game begins, your hand is empty. So, your very first move will always be to claim cards from the display. But, which to claim and which to leave behind? Take two cards from the bottom row and you can ensure your opponent will only be able to snag one of the new cards that replace them. But, anything you take will cause everything that’s left to become cheaper. Are there cards in the current top row that would benefit your opponent? If so, maybe you want to ensure they stay there to make things harder for them.

Add Comment