Agri-cola hits the spot

Twelve full ounces, that’s a lot

Twice as much for a nickel, too

Agri-cola is the drink for you!

— with apologies to the old time radio advertisers for Pepsi Cola. (And, yes, I know it’s pronounced A-grik-a-la, not Ag-ri-cola, but I didn’t learn that for a long while so Ag-ri-cola stuck in my mind.)

My Meeple Mountain friend and colleague, David McMillan, is a huge fan of designer Uwe Rosenberg—so much so he started this series to have reviews of all of Rosenberg’s games here on Meeple Mountain. I’m happy to contribute a review of Agricola to the cause.

Agricola is the Place to Be

When Agricola was released in 2007, it caused quite the stir. Although not the first board game to use the worker placement mechanic (that honor goes to 1999’s Bus or 1998’s Keydom, depending on who you ask), Agricola was one of the first games to catch the wider public attention.

So, why am I covering a game that’s almost 20 years old? In part because it’s a classic game and, in part, because I think Agricola is still worthy of your time and attention.

Allow me to get Agricola to the table to explain.

Farm Livin’ is the Life for Me

Agricola is a farm-based worker placement game. Over 14 rounds, you’ll want to work your fields, fence in areas to acquire livestock, and improve and expand your home. Plowing and planting your fields provides you with food, as does livestock. Expanding your home allows you to expand your family, which means more workers to take actions with.

Sounds simple, right?

(If so, you obviously haven’t played Agricola or any other game by designer Uwe Rosenberg.)

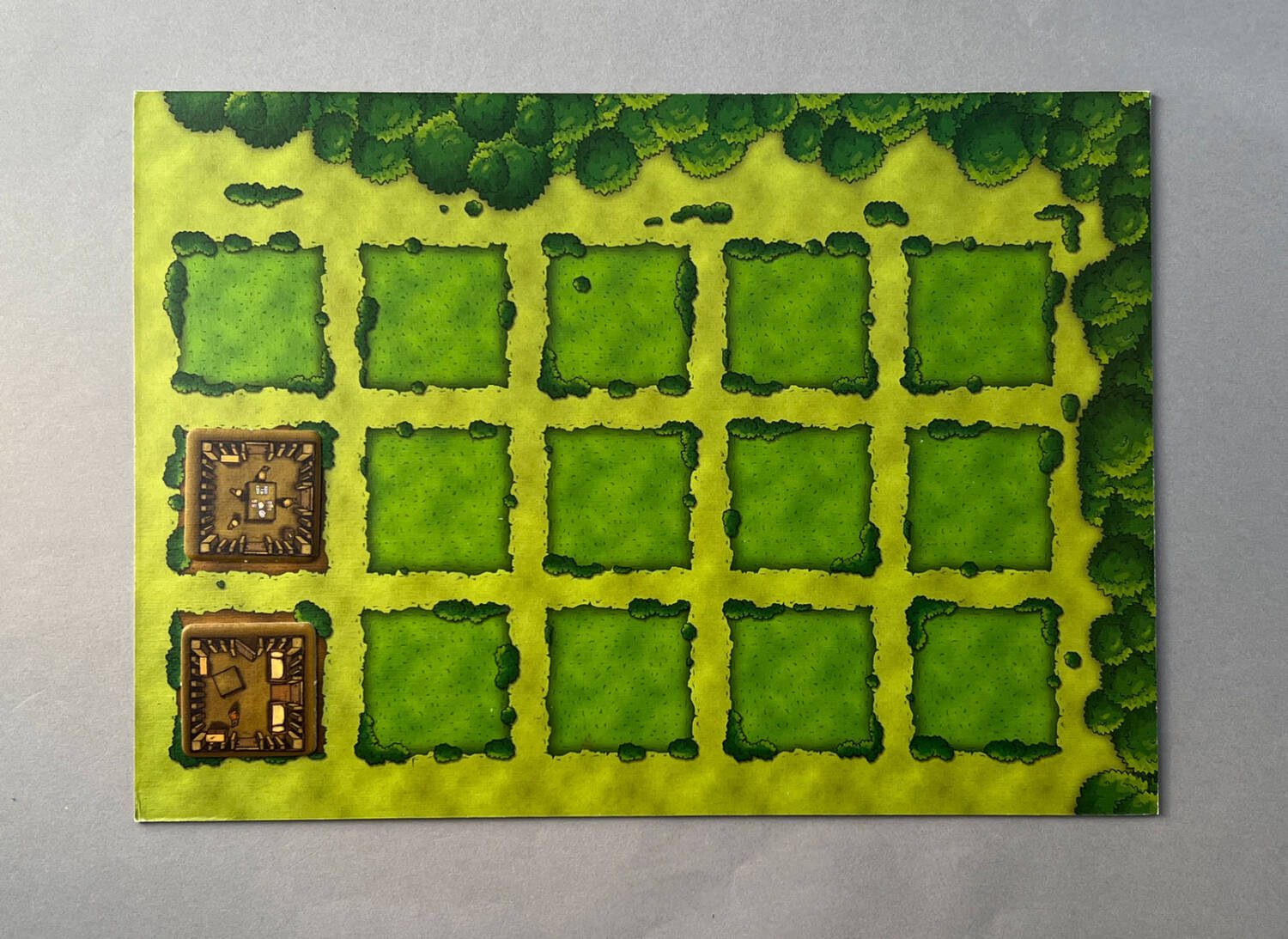

Each player is given a board with their own fifteen-plot farm, with two squares reserved for your initial dwelling.

Players will also receive a collection of five discs, representing family members—two of which go onto the rooms of your house—four stables, and fifteen fences.

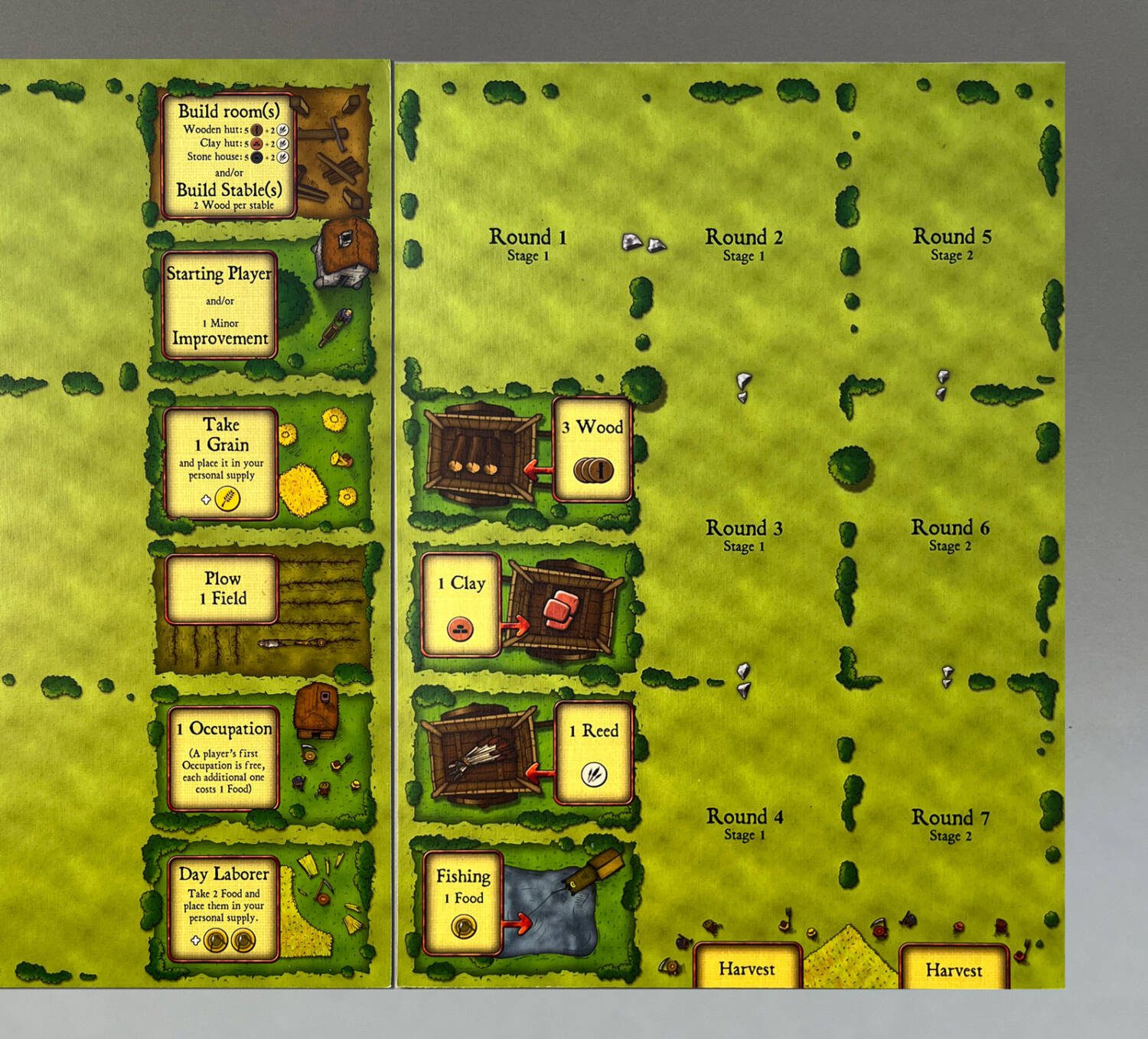

The boards with the action spaces are placed side-by-side. Two of these will have pre-printed actions on them. Shuffle the appropriate cards and place them face-down on their respective spaces.

In addition to the pre-printed actions, in each of the 14 rounds a card will be turned over, revealing a new action available to all players.

Those 14 rounds are divided into six stages. In each stage, the same cards will appear. The order in which they appear will vary from game to game.

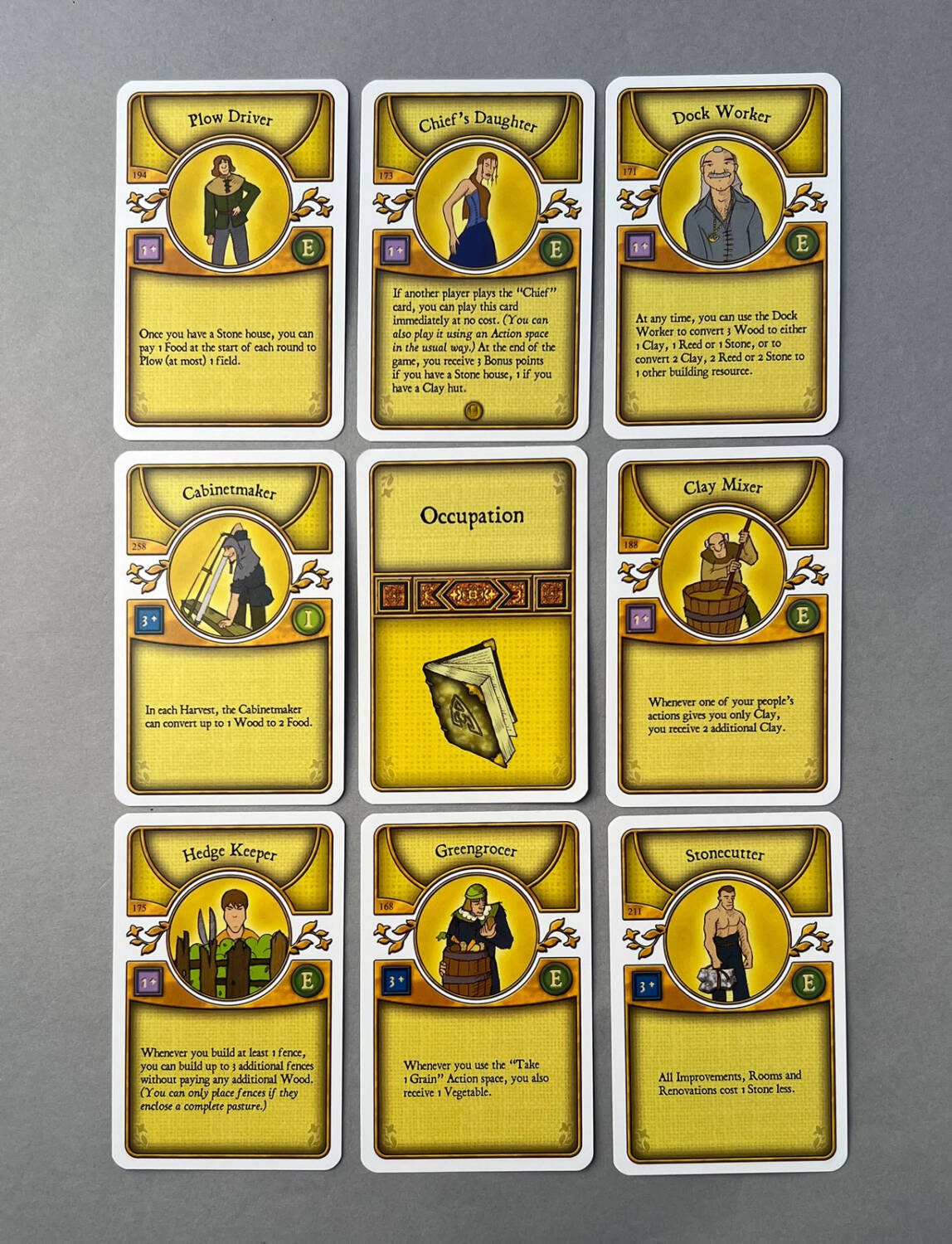

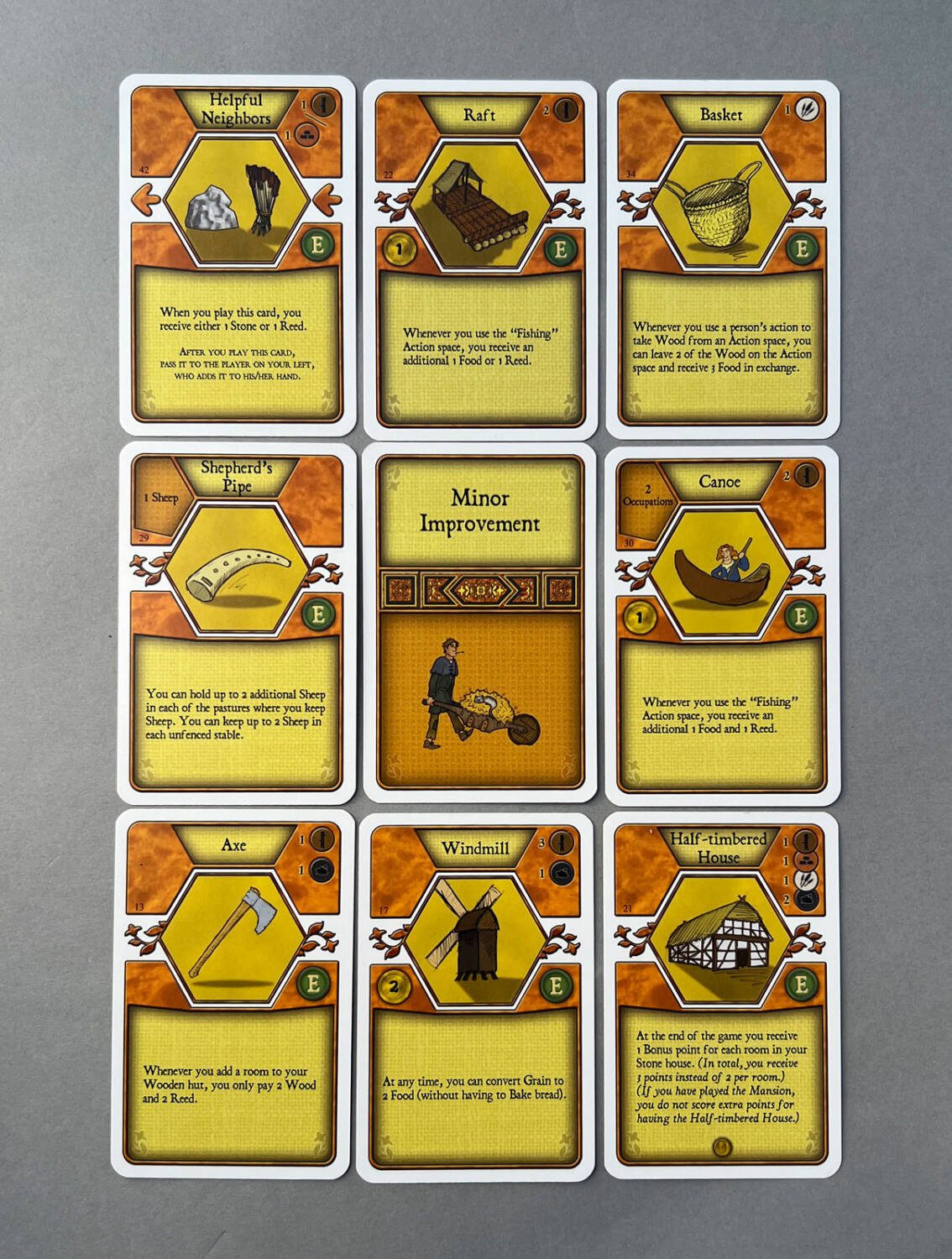

There is a hint of asymmetric powers here as well. Each player starts the game with fourteen unique cards: seven Occupation cards and seven Minor Development cards.

It will cost you an action to play one of these cards (as well as possible resources), but if played early, they can grant you special abilities that can help you shape your strategy.

Turns are straightforward: you’ll take one of your family members and place them on an action spot and take that action—however, only one player can take a given action in the round. When everyone has placed their first family member, the round continues with the next family member. When all family members have taken an action, the round ends and all discs are returned to their respective players.

Land Spreadin’ Out So Far and Wide

Happy farming, however, does not make for a lasting game. There are two aspects of Agricola that make it memorable for me:

Diversify or Lose Points

Your farm is not only your livelihood, it’s the bane of your existence. Victory points are scored for each plot of land you have developed—and you lose points for each plot left fallow at the end of the game. You’ll score points for each of the three types of animal you have at the end of the game, and you’ll be dinged a point for each one you don’t have.

The Constant and Insatiable Need to Feed Your People

Perhaps the most memorable part of Agricola comes at the end of each of those six phases: Harvest. During the Harvest, you’ll need to feed each of your people two food. Now, this may not seem like much, but the ability to gain food—along with all the other actions you’ll be needing to take—can remain a continual challenge.

The first phase happens over four turns; the second takes three turns. This can easily lull a newcomer into a false sense of security. There’s plenty of time to get things done, including waiting on an action the other players are all getting to first, right? Wrong. The next three phases only last two turns each. The final phase is a single turn.

This means you need to get your food production up and running quickly, plowing fields and sowing grains (and, later, vegetables) and fencing in areas to house animals—while everyone else is trying to do the same thing with the limited actions and resources available.

Let’s take Wood, for example. You’re going to need Wood to build fences so you can enclose animals. Four Wood will enclose a single plot on your farm, while six will close in two plots. The Take Wood action, however, only has three Wood on it at the start of the game. (An additional three Wood will be added if no one takes the Take Wood action, but that rarely happens early in the game.) This means you’ll need to take this action multiple times to fence in a plot of land, as well as needing to take the separate Build Fence action. Want to build a Stable to hold more animals? You’ll need two more Wood for that and take the separate action that allows you to build one. What about expanding your dwelling so you can add more family members (and, therefore, take more actions each round)? You’ll need extra Wood, and the special action to build that room, too.

The same holds true for Clay (used to upgrade your dwelling and build Major Improvements like Ovens to bake bread and roast animals) and Reed (required for any dwelling upgrade).

Keep Manhattan, Just Give Me the Countryside -or-

Putting Uwe Rosenberg on the Worker Placement Map and Me In My Place

Back in 2007, I was set to meet up with one of my now weekly gaming partners at our FLGS. When he was delayed, I was invited to join in on a new game one of the other gamers had recently picked up: something called Agricola.

Now, I grew up playing games—all sorts of games—with anyone I could convince to play with me. Early on I had dismissed dice games (Yahtzee? Really? Can’t we each just roll a single die, calling the highest roller the winner and move on to something more challenging? Please?) I pushed my meager collection of largely abstract games on to anyone who expressed the least interest in games for decades. I thought I was a better-than-average gamesman.

Then, that night, I sat down to play Agricola with two people who had played it a lot, and one other person who, like me, who had no idea what was about to hit us.

To say I lost badly is an understatement.

However, that wasn’t the reason Agricola left such a mind-blowing impression on me. I thought about the game throughout the following week, wondering how the two who had played it so well had played so much better than I had. How had they continued to upgrade their dwelling while I was still scrambling to feed my people? What did they know that I didn’t?

The following week, I arrived feeling prepared to take on Agricola anew. I had plans, a strategy in mind, and was ready to put them into play.

And then I managed to do even worse than my first play.

Clearly, I had a lot more to learn.

Goodbye, City Life

Again, Agricola was not the first game to have worker placement as its main mechanic. However, it was, in my opinion, the first game to combine the mechanic with both a requirement for diversification of game elements and a forced efficiency of actions if you hoped to win the game. Put simply, Agricola will punish you if you don’t play in a certain way and do it better than your opponents.

A few years ago, I picked up a copy of the game from my almost-neighbor and Meeple Mountain colleague, Will Hare. Soon thereafter, I brought it to my weekly game night to give it another try.

In the intervening years, I have played lots of worker placement games. As a result, Agricola was no longer the daunting game I remembered. It felt both familiar and easy to strategize. Of course, there were moments when someone else took the resource I desperately needed, or claimed First Player when I needed it. However, I was able to create enough food for my (expanding!) family. I even upgraded my house and improved my farm.

Although the overall mechanics and strategies of the game had lost their arduous newness, Agricola was far from an easy game. My weekly group has played a lot of worker placement games, so playing it felt like we were all those two guys in my first plays who understood how the game needed to be played. And because we all quickly got how the game needed to be played, we were pretty cutthroat with one another.

We had a great time.

Over the years, game designers have expanded on what a worker placement game can be. They have added elements to broaden the ways actions play off of one another and introduced point salads of scoring opportunities. I love Lords of Waterdeep (with the Scoundrels of Skullport expansion!), My Father’s Work, Caylus 1303, Tzol’kin, and Pendulum for all they have brought to the worker placement genre.

And yet, for me, there’s something satisfying about going back to an old favorite, one that proudly displays the very basics of the genre. Agricola is both streamlined and very concise in its approach. All players are competing for the same limited resources in a game that is often decided by only a few points. Every round, every turn matters.

If you are a fan of worker placement games and have never played Agricola, you should.