Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

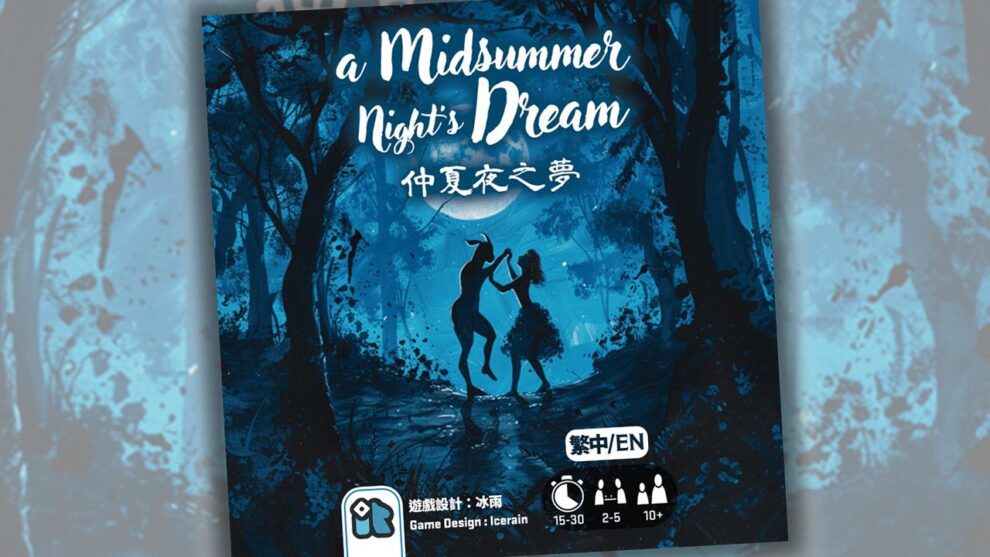

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is not my favourite Shakespeare romcom (hello Ado!) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream by designer and publisher Icerain Lin is not my favourite card game. One of these is a close-run thing, the other less so.

Puck It and See

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a small box card game where players try to empty their hand of cards (card shedding, for example UNO) by playing combinations of cards to the table, always ensuring that the sets of cards they play are higher or one level up from the cards that are already on the table (ladder climbing, for example SCOUT). If I play a pair of fours, then you could play a pair of sixes (higher cards at the same level) or a run/straight of three cards (one level up from a pair, for instance one, two, three).

This isn’t too tricky to start. Players begin each round with 12-14 cards, the majority of which can be one of two numbers. A 3 can be rotated to be a 4, a 5 can pivot to a 2 and so on.

As the round goes on, however, your options become more limited whilst the demands of the round become harder to fulfil. How can you play 4 of a kind when you’ve just got rid of most of your cards? This is where the stack of ‘Love-in Idleness’ wild cards come into play. On your turn you can either play cards or pass and take a wild card. Whilst you can only use one wild card per set of cards, they can act as any number.

If everyone passes then the cards in the centre reset to a pair and play continues, but the round ends if someone passes and there aren’t any wild cards left to take. The round also ends when someone empties their hand. Players total up the broken-heart penalty points on their cards and subtract that number from their current score. When a player reaches 0 on the scorecard the game is over and the person with the highest remaining score wins.

The course of true love never did run smooth

Like its source material, A Midsummer Night’s Dream is at once light and breezy and a bit of a (love’s) laboured slog. Allow me to explain.

Turns can be quick. Since most cards have a choice of numbers and there’s no immediate cost to passing in a round, the early turns of a round are wide open. You could be staring at 22 or more possible numbers on your cards with what feels like infinite combinations. It’s an overwhelming choice with no steer as to what you might need to hang onto for the rest of the round and little idea of what other players might be holding. At the start you’re choosing cards to play almost at random.

It’s also hard to plan ahead when you don’t know what will be in the centre of the table on your next turn. Others might pass, leaving you needing only a single step or two up from what you placed on your last turn, or the other players might have scaled most of the ladder leaving you reaching for a combination of 5 cards.

You’re trying to read the future in the flawless porcelain of a new teacup.

And predicting the future whilst leaving yourself options is important. The cost of not being able to take a wildcard when passing (and so ending the round) is huge: you lose the points on the cards you’re holding and an additional 10 points. It’s a steep penalty and often there’s nothing you could have done to avoid it.

It’s only from the mid-point of a round that you can start to plan for future turns in any coherent way. However, by then wild cards are drying up and the steps on the ladder are so restrictive against the number of cards left in your hand that it’s almost pure luck whether you can play a turn or not.

The result is a game that feels like it should be quick and teasing but can slow to a crawl as each player on their turn calculates and recalculates their options, trying to ensure that next turn they’ll be able to play something.

Take Pains. Be Perfect.

It’s also a game where passing to get a wild card is often a better move than actually playing a set of cards, which seems counterintuitive given you’re trying to get rid of all the cards in your hand. The restriction of needing to have a suitable set of cards to play out is so tight that having a couple of wilds ready in the second half of a round can be the difference between winning and losing. Especially since the cost of having a wild in your hand when the round ends isn’t that bad (3 points compared to busting and automatically losing 10 points).

I’ve never actually seen a player do well in a round without passing at all. As well, rather than a player emptying their hand, the vast majority of rounds I’ve played have ended in a player being unable to play a set of cards when there were no wild cards left. In fact, several of the rounds I played featured an early run on the wilds, with players only starting to take proper turns once the stack ran out.

When players are forfeiting their turns automatically, part of me wonders if it would have been simpler just to give each player two wilds and say there’s no passing. Which would be a shame, since the decision of when to pass could be interesting. The problem, I think, is that the cost of passing should be higher but not so high that the need to pass in almost every round is too punishing. Passing in A Midsummer Night’s Dream feels like it could have a flavour of the dynamic of debt in a Martin Wallace design but isn’t quite balanced tightly enough.

Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind

This mechanical juxtaposition of grinding froth extends to the artwork as well. As themes go, there’s no link between the setting and gameplay. But the artwork is wonderfully resonant of teen romance fiction, perfectly fitting the absurd drama of the source material.

It’s also created by Midjourney’s generative AI, which raises deeper issues. I’m not a fan of generative AI, for moral and environmental reasons, but I confess to being conflicted here. Designed and developed by Icerain Lin and published by Icerain Games, A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a one-person effort and AI has allowed Lin to release a game entirely themself. It’s a subtly different use than a bigger publishing company using AI for its art to save money. As a person whose own artistic talents wouldn’t impress in a kindergarten, the resulting outcome of AI here makes me smile, even if I don’t like the technology that enabled it.

Lin has stated that if the game receives a positive reception, then publisher EmperorS4 (who have subsequently picked up the game) may rerelease A Midsummer Night’s Dream with human-illustrated artwork. Despite my reservations about the game itself, I hope that dream turns into reality.

If we shadows have offended

A Midsummer Night’s Dream has left me conflicted. I went in expecting to watch a romantic comedy and instead I got Shakespeare’s play. Technically I got what I wanted but the reality is a good deal more convoluted than necessary.

There are some good ideas here but perhaps some additional names on the credits might have helped those good ideas coalesce into a good game. The muddled English rules, fiddly scoring track and dull two player experience don’t help matters either.

Yet, there are moments that shine. Although the start of a round is too open and the end too constrictive and reliant on luck, A Midsummer Night’s Dream works best at the midpoint of a round, when you aren’t overwhelmed by options and feel like you can steer your ship towards surviving. In that Goldilocks sliver between the infinite possibilities of dreams and the restrictions of reality, there’s a spark of joy that feels good.

Sadly, it’s hard to hold on to just a spark.

Add Comment