Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I grew up surrounded by pop culture representations of Robin Hood. The 1990’s were a boom time for the Sherwoodian economy, with popular Hollywood adaptations, more enduringly popular Mel Brooks parodies, and the more-or-less permanent availability of Disney’s animated 1973 Robin Hood film on VHS. You too may have formed some of your earliest memories while staring at the McDonald’s toy display during the 1995 Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection campaign. Oo-de-lally, oo-de-lally, golly, what a day, indeed.

There’s something magical about Robin Hood, isn’t there? Like King Arthur, he exists in that wondrous folkloric pocket between the historic and the fantastic. While the story of Robin Hood doesn’t typically involve sorcery, there is still an aura of magic to the whole affair. Sherwood Forest exists in the real world, yet to set anything there is to invite the same gossamer feelings and suspension of disbelief that come with finding out a story takes place in Neverland. I am instantly drawn in.

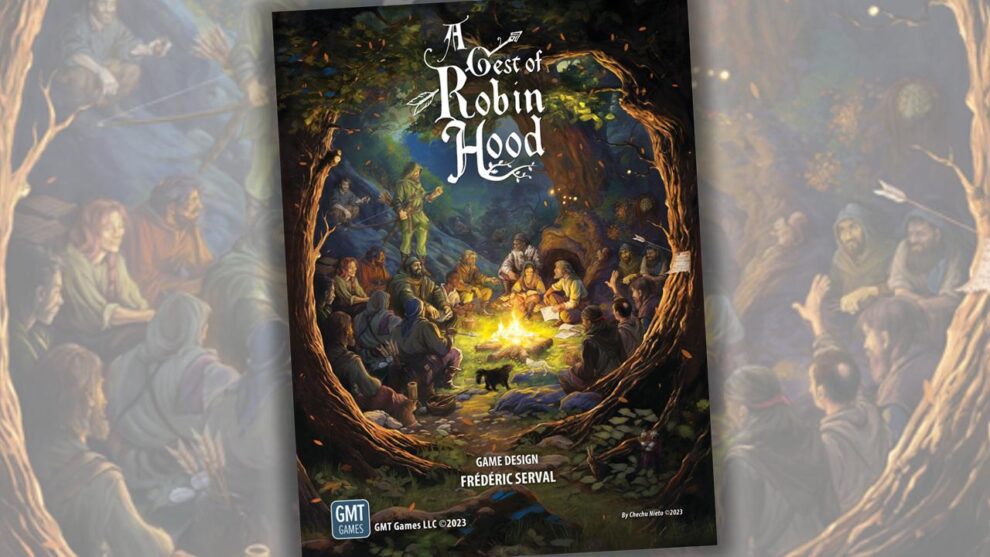

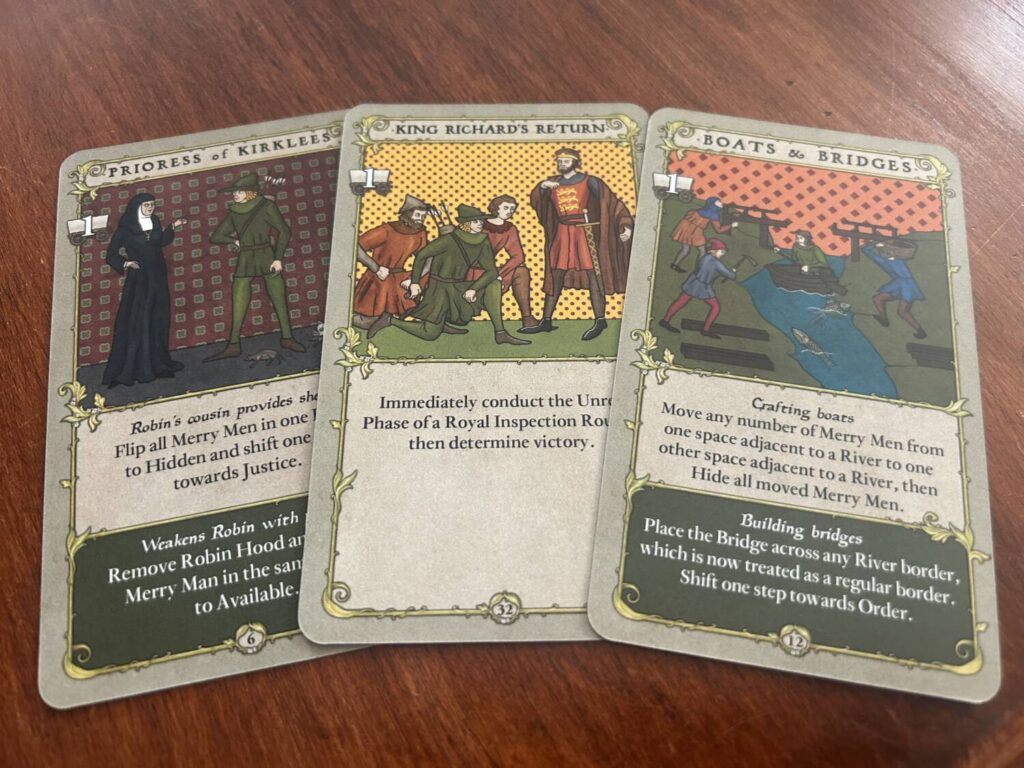

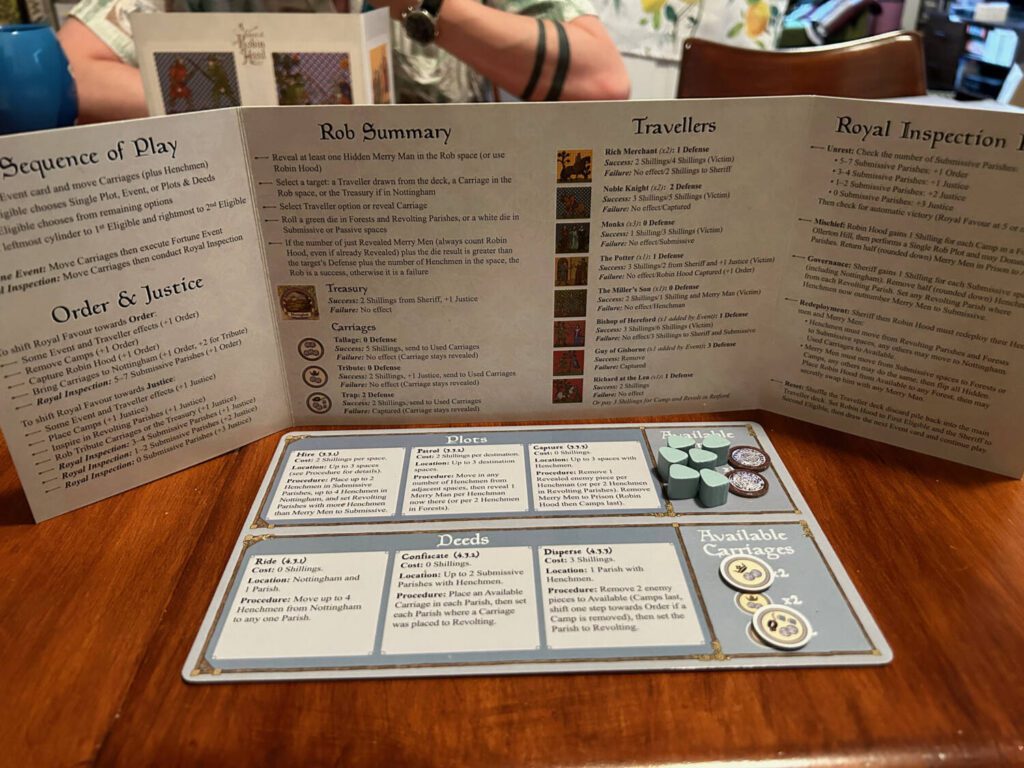

Publisher GMT knows what they’ve got on their hands with A Gest of Robin Hood, a two player game that recreates the fight between Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham. Every production choice makes the most of the story. The cover, which shows Robin Hood and his Merry Men surrounding a fire deep in the forest at night, knows the magic of these characters and this setting. The board, my favorite game board GMT has ever published, resembles a parchment map of Nottinghamshire, and does so without sacrificing functionality. The cards are embellished with illumination-style illustrations. The presentation is, quite simply, very good. I’ve written previously about the ways in which GMT’s art department has stepped up its game, and Gest is further evidence of that.

Sure, It’s Beautiful, but What Is It?

A Gest of Robin Hood is the second installment in publisher GMT’s Irregular Conflicts Series, which is itself an off-shoot of their storied COIN line. The COIN games use a fairly straight-forward system to depict historical engagements in COunter INsurgency situations. Don’t confuse the simplicity of the system for a light rules load; the COIN games dress that frame in all sorts of frippery. Irregular Conflicts, which began with Vijayanagara: The Deccan Empires of Medieval India, 1290-1398, applies that same great COIN taste to historical events that don’t fit the counter-insurgent framework.

That is inarguably one of the more boring paragraphs I’ve written in my time at Meeple Mountain, and I apologize for that, but the facts of the matter are as they are. There’s no getting around it. We’re talking about GMT games. We’re in textbook territory.

In Gest, each player has a different goal, which must be accomplished before the return of King Richard the Lion Hearted. Robin Hood wants to bend the long arc of history towards Justice, while the Sheriff of Nottingham seeks to instill Order.

Now there’s a nice, clean, anti-fascistic viewpoint for you. My goodness. I’m sweating a little.

Gest is a COIN game in all but name, really. The structure of each turn is identical, as evidenced by the fact that I am now going to (more or less) copy and paste my own round description from my review of a COIN game:

- The top card of the event deck is revealed.

- The player with initiative chooses from one of three options—Single Plot (a standard action), Event (activating the action on the card), or Plot & Deeds (a standard action with added paprika)—and either executes their choice or passes. If you pass, you take some money from the bank.

- The second player chooses between the two options the first player didn’t choose, and either executes their choice or passes.

You wash, rinse, and repeat that order of events until a Royal Inspection is revealed from the Event Deck, at which point both players check to see if either of them wins the game. Provided neither does, play resumes until the next Royal Inspection. It’s a bit like everyone’s running around, roughing about, until the teacher returns to the classroom. Then, suddenly, everyone’s sitting on their hands, whistling with the utmost level of nonchalance.

Each side has a distinct set of Plots and Deeds available. Some are (roughly speaking) the same action under different names. Robin Hood Recruits while the Sheriff Hires, Sneaks where the Sheriff Patrols. Though it takes a while to grow comfortable with the ins and outs of each action, the broad strokes are easy enough to internalize.

The bulk of the conflict in Gest comes down to the state of each Parish. Is it in Revolt, which benefits Monsieur Hood, or does it Submit, which pleases Mr. Sheriff? It is in Robin Hood’s interest to get as many towns revolting as possible. The Sheriff of Nottingham, ever the responsible fireman, wants more of a controlled burn. The only way his side can gain any money, necessary to perform actions, is by Confiscating, which sets the locals on edge and causes Revolts. The trick is making sure you’re well-positioned to flip that town back to Submit afterwards.

The carriages that transport confiscated materials from the Parishes back to Nottingham have to travel slowly via roads, and can be Robbed by the Merry Men. This is my favorite part of the game, this little side system. The carriage tokens are cute. The process of deciding where to Confiscate on the board, based on the positions of the Merry Men relative to the paths back to Nottingham, is fun. Provided the Sheriff has kept their carriages well-attended, the dice roles for Robin Hood’s robberies are a welcome injection of dramatics.

I Am Not a Merry Man

Be mindful, like any COIN game, that it is very easy to back yourself into a corner in A Gest of Robin Hood. In my first game, playing as the Sheriff of Nottingham, I was basically out of the running by the third turn. I didn’t know that until maybe two or three turns after that, but I know the moment I did myself in, and it was well before I felt it. This is a finicky decision space, one in which the rigidity of order of operations plays a big part.

For me, that rigidity keeps me from loving the game. A Gest of Robin Hood doesn’t give you much responsive freedom. You can’t pivot, really, at least not in a way that feels dynamic. Attempting to change directions or focus feels, instead, somewhat creaky. That’s appropriate for the setting, and I don’t think it’s a knock against the game. Just a personal reason for not getting more hung up. As my friend Boris said after our game, “It’s good, but I don’t know that I had fun.”

If you’re of a mind to play this game more than a handful of times, and you find yourself buying into the system, it does offer a great deal of trade-offs, of turn-to-turn and long-term tensions, and it’s approachable enough that you can teach someone new how to play in about 15-20 minutes, and quick enough that you can be done in about an hour. It is, even if not for me, a good game. Designer Fred Serval, who designed the excellent Red Flag Over Paris two years ago, has equipped himself well here.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have to call some galleries to get quotes for framing this board.