Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

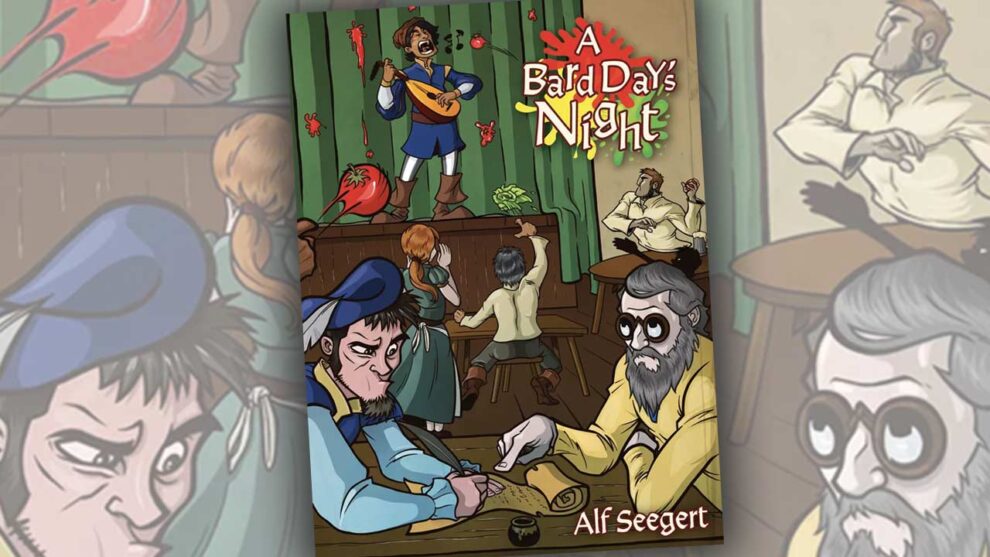

As I began exploring Alf Seegert’s back catalog in 2023, his titles casually became nominees for my favorite game of the year. The Road to Canterbury (2011) received the crown. His similarly medieval duel, Illumination, deserved its status as a contender. I was ready for more with the release of A Bard Day’s Night, a strange little card game of relinquishment and reclamation.

And, like a dog, in work I’ve pro’en adept

A grid of cards containing fantastical characters and food: lettuce, onion, tomato, salt, and cider. One ballad card from a hand of five goes into the grid, one food card comes out in exchange.

Players grammatically arrange the columns with subjects, actions, adjectives, objects, and, most excitedly, relative pronoun clauses. A frivolous young monk / boldly wields a spatula against / a surly / troll / who is cursing a vindictive warlock, for example. Each ballad card bears a color scribble matching the primary food cards: green, yellow, and red.

When a ballad row is complete, players use their acquired foods as currency in bids to reclaim ballad cards by color. If you’ve planned well, you’ll be ready with a bevy of tomatoes when a red-heavy ballad hits the market. Salt cards serve as wilds. Players can only bid one food type per auction, and only five total food cards. A cider card in the bid indicates a play for two colors, but the limit remains five total food cards.

Why all this back and forth? At the top of each ballad card, a theme icon is the true object of the hunt. Through the rigamarole of giving and taking, players are really in the business of collecting these icons in hopes of having the most of each type at the end of the game. A side track holds a token for each of the six icons, indicating the number of coins (points) that will go to the supreme collector of each at the end of the game. Every time a ballad row clears from the grid, the player who collects the adjective in the III spot swaps two adjacent tokens, altering the endgame scoring. The only restriction on the swapping is against reversing the most recent exchange. I’m glad, because that would be tedious.

Cider cards also manipulate the grid, swapping cards before laying new cards into play. This might alter the color balance of a ballad or prepare for a bid. With every completed ballad, a new character enters the fray until the stack runs out.

The cards in the V spots are songscape cards that feature a staff of notes across the bottom and half an icon on the left and on the right. Collect fives, match up the partial icons, and score points for the set.

When, like a log, shouldst I have deeply slept

A Bard Day’s Night is odd, an endearing hallmark of designer Alf Seegert. For a set-collecting game, several bewildering narrative hoops await. Give up cards in exchange for other cards, only to spend those other cards to get the original cards back? And all for an icon that was on the original cards in the first place? Right.

Layering intentions, however, is Seegert’s other hallmark. The Road to Canterbury featured card majorities spent to achieve cube majorities spent to accumulate map majorities. Illumination is all about selecting grouped tiles from one area to place in other areas to amass majorities of multifarious antagonistic pairings. Trying to shove these games in a nutshell involves a series of nested thoughts that at first seem dissonant. In practice, however, they produce unexpectedly beautiful and thematically cohesive movement.

This particular minstrel’s tale is a constant tug-of-war with several ropes, an attempt to accumulate bidding materials while altering the progress of the available ballads to make sure you’re ready to bid when the final relative pronoun clause drops. All the while spending several ballads trying specifically to acquire the III-adjectives to slide those theme icons up the track. Or aiming to acquire the icons that are already high on the track. Truth be told, most of the time I’m not certain I know what I’m doing or whether I can even get within sight of the things I’d like to see happen. There’s no shortage of interesting here.

I’ve tried A Bard Day’s Night with two, three, and four players. Each additional player feels like a further loss of control. The duel highlights battle on the theme track because you can’t simply undo what your opponent has done. You must choose elsewhere and worry about the most recent setback later—a lovely restriction. With four players, though, it might be two or three ballads before you have a shot at the theme track at all as you watch your best intentions evaporate. Vanity of vanities: a wispy life at the whims of fate. The included Tavern module issues rewards for various conditions. It’s good, but isn’t strong enough to compensate for feeling like you’re along for a ride.

The flipside is that the winning score in the four-player affair is much lower, so winning even the bottom tier of the theme track could win you the game. And I’ve not even mentioned the impact of a good effort in the songscapes.

Tactically, there is value in paying attention to every collected food, every salt shaker, in order to decipher your opponents’ intentions—which cards they’re chasing, or half-chasing, or not chasing because a losing bid or a no-bid also results in collecting bonus food cards for the future. All ye card counters might just rejoice over a game like this as the head games take center stage.

Each thing thou does at home when I alight

Then again, it’s also entirely possible to play this tavern game without a care in the world about winning. Say again?

A friend hit the nail on the head when he said there are party game vibes in here as well. The ballads are whimsical when they are finished. I would be lying if I said I never slipped a badger in the IV spot (the object) just to make the ballad title funny. Perhaps I regretted it immediately afterward when I didn’t have any onions for the bid—especially after I was the one who made the thing so yellow-heavy in the first place. Whoops. At least I got a good laugh out of it, right?

It’s fun to read the titles out as they go up for bid, even if you don’t win. I doubt that was the entire point of the design, but it’s in there. In this way, I’m reminded of the only other contender for my 2023 game of the year—Pessoa. The Pythagoras title from Orlando Sa is one of the oddest, tightest, and most delightfully thematic worker placement games I’ve ever encountered. Pessoa is premised around building runs of poetry cards, translated from Portuguese and loosely pasted together to the point that they are, at times, hilarious. It’s hard to categorize that blend of rigid mechanics and buoyant fun, but sometimes you play with frivolity as a key objective.

When the dust settles on the silliness, however, there is a very real battle lurking inside A Bard Day’s Night. The comic-style illustrations from Giulio Fanfoni are playful. The food cards are bold, colorful, and simple. All the while, those who want to master the necessities of forceful victory have little room for attention deficit. Seegert sets this table for battle.

Doth make me thus to feel that all is right

Still, I’m not sure how seriously to take it, which is why it’s not my favorite of his games. His other titles dwelt securely in the thoughtfully irreverent, which allowed me to smile while I was sweating over the multi-faceted gameplay. Here the chuckles very nearly get in the way, detracting from the effort required by the cards. I’ve enjoyed every play as have those who shared the time at the table. Folks universally marveled at the twist on card collection, but none were so enamored as to request it again.

Mechanically, the recipe works. A few belly laughs are always welcome. My affinity is definitely stronger for other Seegert titles, but I’m happy to have had the chance with A Bard Day’s Night. Why on earth should I moan?