Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Without my realizing it, Looping Games have been in my head for the last few years. Their 19xx series of games have snuck onto my most anticipated lists (both in 2021 and 2023). They have shown up in conversation. But I had never actually played a game or even seen a box to lock the series into place mentally.

As a friend was telling me how excited he was to finally get hold of 1987 Channel Tunnel, all the pieces clicked and I realized how this collection of titles in their novel-sized boxes belong one and all to the same publisher. I’m sure there’s a fun conversation around the origins, size, and hopes for this series of 20th century historical outings. For the time being, I’m happy just to give them my attention.

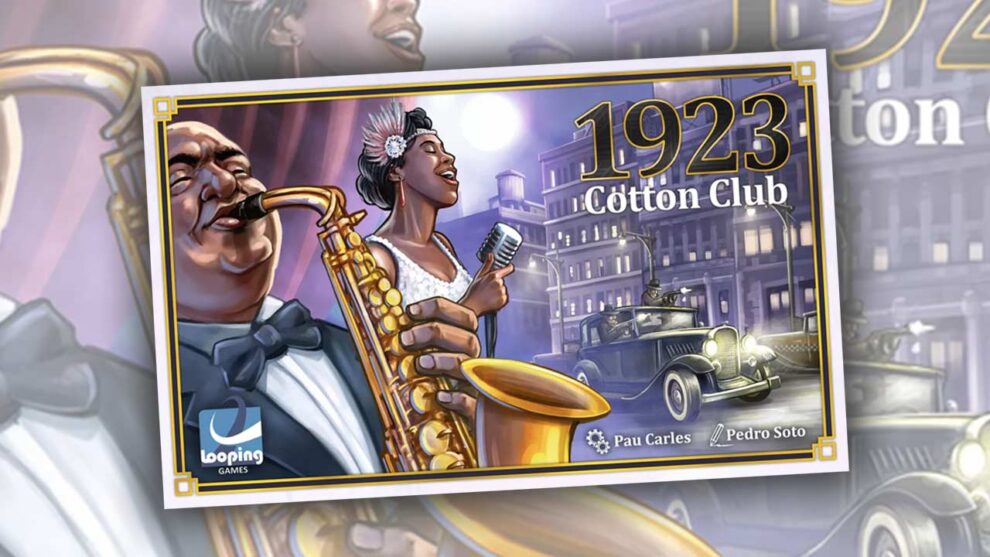

The Cotton Club was formed in, you guessed it, 1923 by bootlegger Owney Madden in Harlem. A racially segregated clientele were often entertained by the legends of the jazz age in the presence of famous gangsters, politicians, and celebrities. 1923 Cotton Club is a worker placement game that sets players as club owners in the days of prohibition, building up their wares in an attempt to build the best establishment and draw a notable (regardless of nobility) crowd.

Riding the icon train

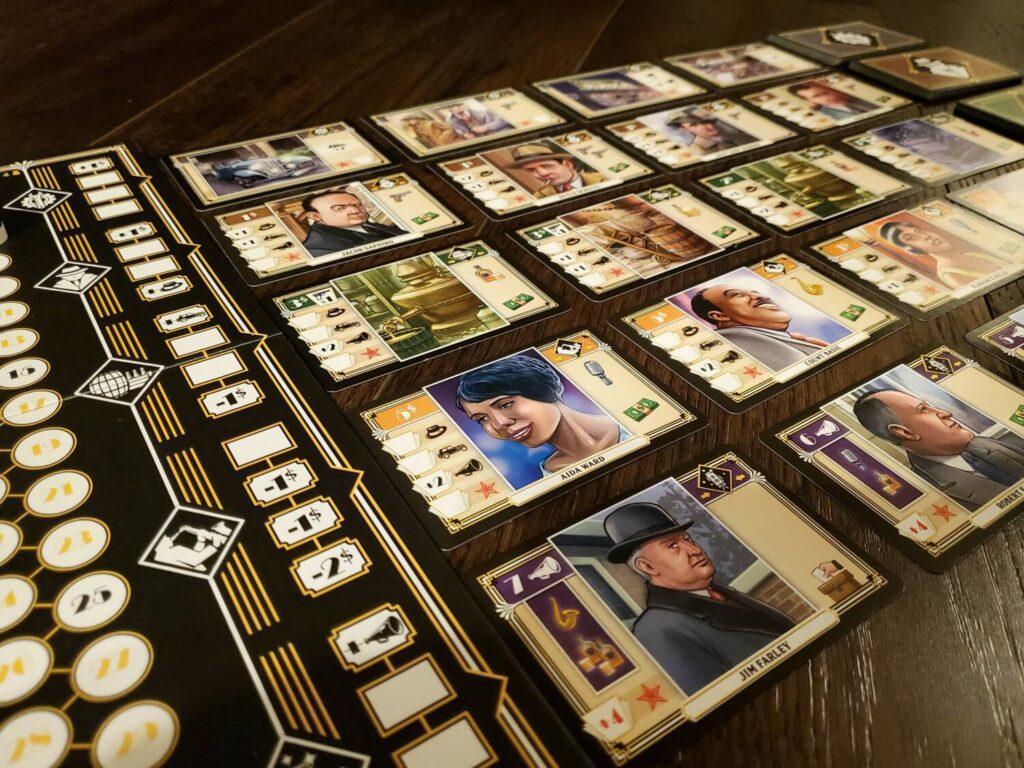

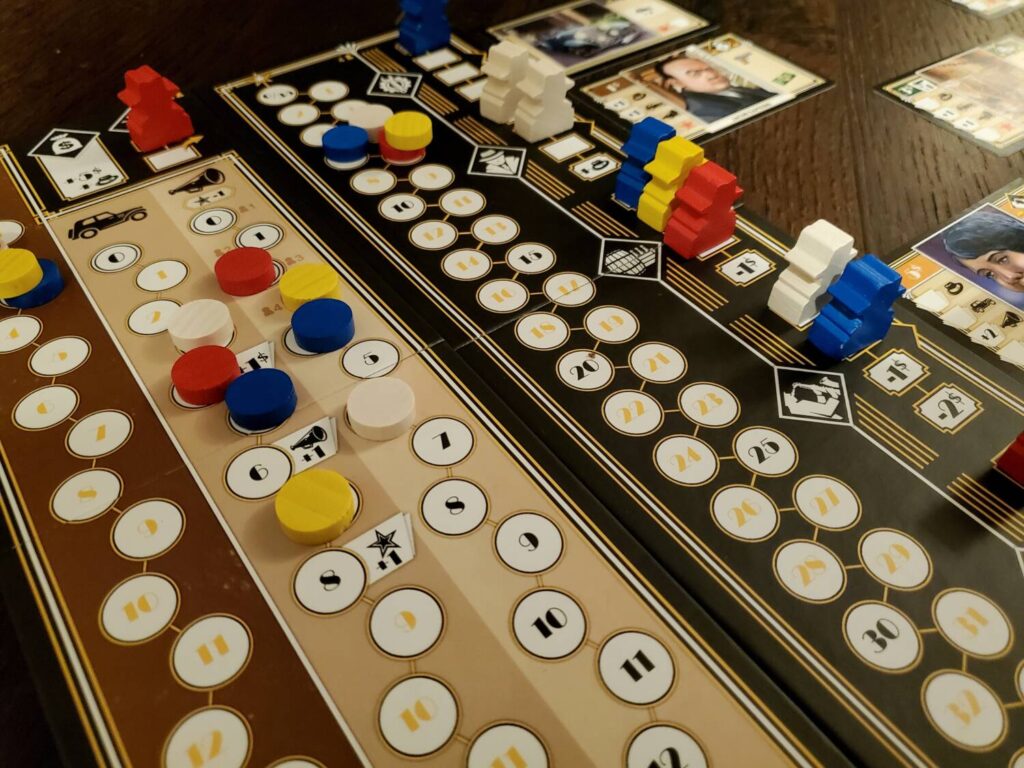

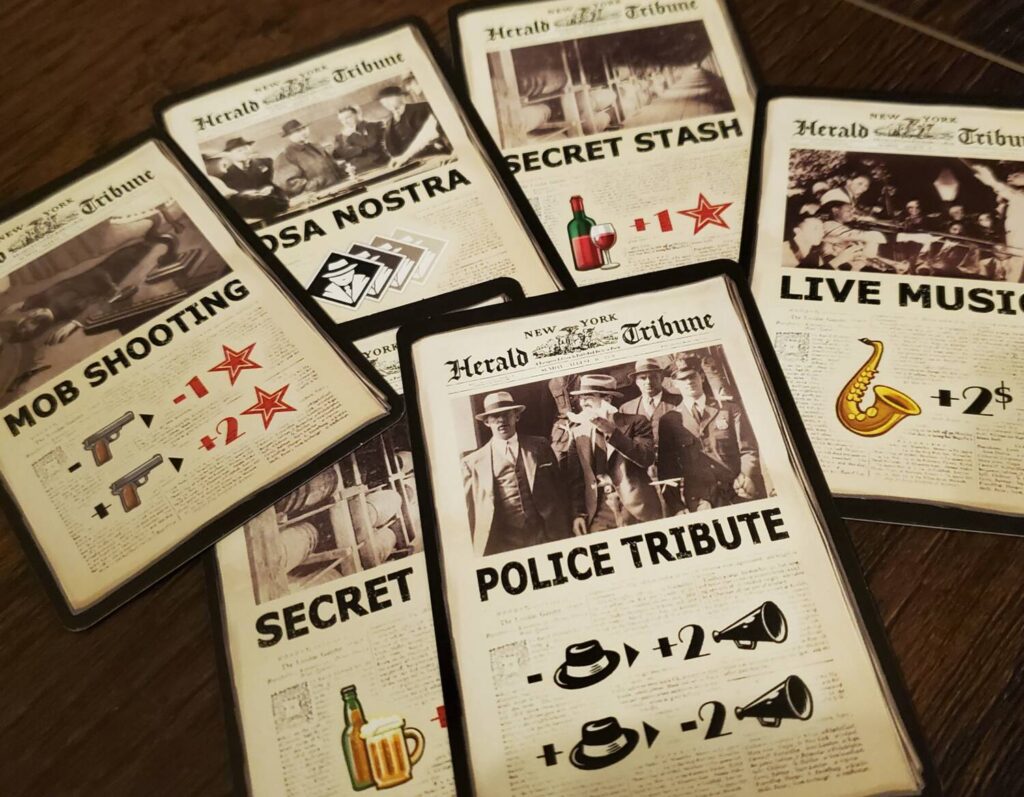

The central play area of 1923 Cotton Club is a tableau market of five card types flanked by three key tracks. Players send three workers into each of six rounds to collect cards and their attributes for their club while moving along the tracks. Rounds typically end with a revelation of previously hidden events that reward, penalize, and otherwise shift the balance of the club scene.

The cards have specialties. Club improvements are track movements that can sometimes be bolstered through cash payments. Gangsters bring guns and income and guns. Smuggled alcohol gives the club flavor, cash, and a tinge of notoriety. Performers lend their talents and, yes, more money. Celebrities score significantly in the endgame and, in the case of politicians, open the door to bribes for a more lenient position on the criminality track.

Acquired cards are tucked under the player’s club board in a train, leaving only their attribute icons visible. In this way, player clubs take on personality, a penchant for singers and wine, maybe, and a few more hired thugs than necessary. These personality traits are then tested by event cards. With the exception of the first round, players have the option of playing cards into the event cache that will trigger at the end of the round. Events might give bonus income for dancers or endgame points for whiskey. Most interestingly, they could either reward or penalize excess guns and criminality. It all depends on the shifty morals of the world lurking in the events.

For those who can’t stand to leave their fate to the realm of surprise, there are two Tip-off spots on the board where players can peek into the coming events in the hopes of preparation. Of course, paying attention to the sudden changes in direction following a visit to the Tip-off might help other club owners predict the future. Then again, maybe it’s a great opportunity for misdirection. Best yet: the Tip-off comes with a deferred action. After all player meeples are out, the folks who visited the inside track move those meeples to one of the remaining spots to take a bonus turn. Usually this is good, but some of those final spots might come at a price.

Folks in need of quick cash have an option for a loan of questionable origin—questionable because it comes with a bump on the criminality track. Most of the cards come by way of cash gathered via the income icons. Celebrities require a different currency: influence. Players move up and down the influence track as they earn and spend their way to prominence.

And so it goes. Players visit spaces, collect cards, move their markers and cultivate an effective club until the sixth round ends and players tally scores. Influence and Initiative (turn order) tracks give bonus points. Criminal supremacy results in a loss. Cards lend their value and the winner is the club owner with the most points.

Cotton clubs sound awful gentle

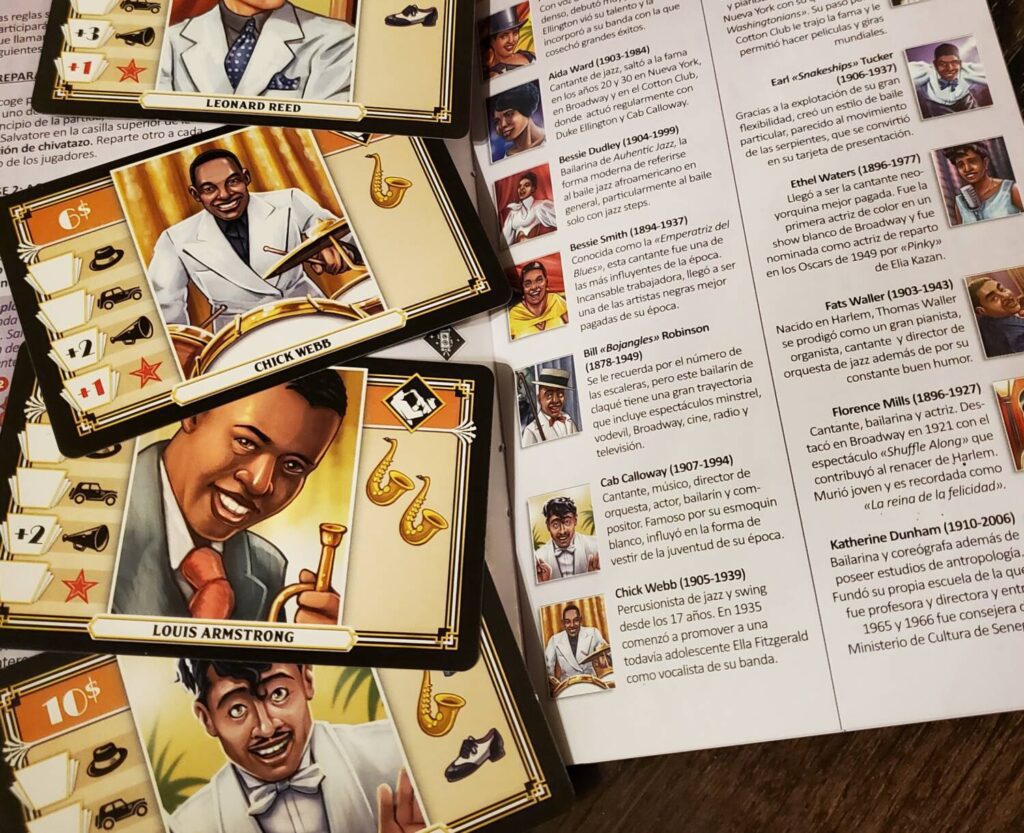

Let’s start with Looping Games’ attention to historical detail. The fifty-one human cards each have a biographical blurb in the rulebook. I love that I can read about Count Basie, Aida Ward, Jimmy Durante, Bugsy Siegel, and Salvatore Maranzano when their cards appear. The rulebook also contains a note on the racial injustice of the day, the tendency to allow for black performers on stage but not as patrons at the front door.

Outside the written word, the game’s mechanics also engage the cultural moment of proprietorship during prohibition. Gin joints require gin, and the law was the law. The criminality track is a matter of consideration from the beginning. Topping the track will result in a penalty, but a modest one, so maybe it’s worthwhile? It’s possible a crackdown on all those guns results in a loss of cash as well. Of course, sometimes the criminal element is nearly all gain and the extra smuggling results in a boon. It’s all in the event cards. Cotton Club brings a nice little tension to that consideration by inserting the unknown.

Each card type has three available spots on the board. The first comes with a bonus, the second is neutral, and the third carries a cost. Every round’s needs must be weighed against the market and the opposition. Mind you, it’s not all that rigorous. It’s mostly mild. The early rounds are a rush for gangsters and beer. A quick glance at the influence track late might predict a dogfight over certain celebrities. Each celebrity offers a discount for the right combination of icons. It’s easy enough to know which cards might disappear first if one wants to get their hands dirty in the pursuit.

One area that works fine but might raise an eyebrow or two is the two-player affair. A third meeple color enters the fray by a mix of a predetermined pattern and player decisions. This creates the predictably unwanted interference of a third player with a bit of intentional blocking by way of player agency. For those wanting a pure head-to-head engagement, 1923’s third wheel might not work.

If I have a beef with the game, and it’s a small one, it’s in the physical handling of the cards. I don’t have a game table, so plucking cards out of a 4×5 grid and tucking them into a train under a dozen other cards can feel a bit silly at times. But I do like the idea of that train of icons. In the four player game you’ll stretch out a distance with all those cards—reminiscent of First Class: All Aboard the Orient Express in many ways—but it reads well on the table.

I’ve not mentioned the initiative track much thus far, but turn order matters in the club game. Players move on the track via the cards. Hanging out in the last position often means both the best cards and those precious bonus spots are gone when they’re needed, and catching up requires effort once you fall behind. In some ways, this highlights the need for balance in the collection effort. No one icon or track can dominate the effort, or one leg of the strategy might collapse.

Which speakeasy wore it best?

A while back, I reviewed Speakeasy Blues from Artana Games. The two titles beg comparison. Both draw on the same era with the same idea: run a profitable club, welcome the big names, and figure out the criminal element. Of course, the Blues worked by dice placement, where the Cotton Club uses meeples and bonuses, but they do have a lot in common.

In this case, the simplicity of 1923 wins the day. I really do love the art deco style of Speakeasy Blues and the dice mechanism is fizzing, but the scoring in the Cotton Club is more intuitive and the box size (not to mention the box art) makes a difference without missing a punch.

Matching my experience with the 19xx Looping titles thus far, 1923 Cotton Club is a solid play in a small package. 110 cards, a few boards and meeples, a frank history lesson, and a load of simple charm. I’m impressed with the hour this one provides. Light on the complexity, but interesting with its engagement. Pedro Soto’s artwork (Red Cathedral, Bot Factory, Moesteiro) fits the overall aesthetic and the mechanics deliver. A bit of pesky tucking aside, Cotton Club is definitely worth checking out.

As I work my way through the Looping 19xx series, I’m keeping my thoughts in order with a ranking. I will provide/update that ranking with each review:

- 1987 Channel Tunnel

- 1923 Cotton Club

- 1902 Méliès