Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

At first glance, the explosive ending of 1920 Wall Street doesn’t seem like much as a game mechanism. Like its counterparts in the 19xx series from Looping Games, 1920 is an effectively thematic endeavor. As the story goes, a horse-drawn carriage exploded in New York City on September 16, 1920 in front of the J.P. Morgan building—one of the first studied cases of terrorism, one that happens to be unsolved to this day. The game mimics a vibrant market that is ultimately, even if temporarily, upended by explosion. In real life, the market was open the next day. True to form, then, 1920’s explosion stirs the pot but fails to halt the final valuation and declaration of a winner.

Regardless of first impressions, however, players will undoubtedly remark in the endgame about the impact of the explosion and the need to be more attentive next time.

1920 Wall Street (hereafter referred to as 1920) is a card-driven stock trading game. Players travel around a rondel, purchasing cards, changing market values, collecting shares, and exerting themselves to determine the effect of the final explosion, after which total money rules the day. In many ways it’s exactly what a stock game ought to be, with a dash of disruptive historical flavor.

The end

Two anticipations govern the decision-making in 1920. The first is the aforementioned explosion. From the outset, players discard into one of three locations, each tied to a particular aftermath of the dynamite. Again, they don’t look like much. One disarms wild cards, one decreases player stock counts by one, and the other halves the valuation of the game’s four companies universally across the board. When the fuse runs out—that being the deck of cards—the pile containing the most dynamite icons goes into effect.

The second anticipation is tied to the minimum ownership requirements of each of the four companies. Throughout the game, players wrestle with the options to decide whether to move market values or chase shares. The various decisions in the game’s central rondel require discards from the player’s hand, and those discards often strike at the player’s share count. The idea is to maintain a balance of the right shares—the ones that will be worth the most, of course—while making the right sacrifices to set the values high. The thresholds are hardly massive, but by game’s end neither is the count of cards in a player’s hand.

Perhaps now you see the impact of one of those explosive decisions. Decreasing player share counts by one? Yes, one share can ruin a good many things for multiple players. One attempt to mitigate this threat is the use of wild shares, precious gold cards that can shift allegiance and make up differences. That is, of course, unless the explosive lot falls on disarming the wild cards—which then assume a mostly harmless cash value and count toward no company affiliation, damaging hopes of widespread personal gain. But if a player has a decent set of mostly harmless cash, the explosive best might be in halving the worth of every stock, shifting the balance and very definition of value to include those cards of gold.

It really is interesting—more interesting than I expected.

The beginning

Rondel movement is the most common action in the game. Players move around a ring of cards at will in the set direction, purchasing the landing card by spending an amount equal to the number of spaces moved plus the value of the card. Players maintain an increasing base spending value throughout the game and pay costs beyond their base with coins. Purchased cards either enter the hand or head immediately to a discard pile for the sake of their dynamite icons.

Selling stock in-game is both lucrative and costly. The card in the player’s rondel location goes to a discard pile. A stock card from the player’s hand takes its place in exchange for coins, and an additional card from the deck joins the space, creating a mega-buy for a future player. In this way the game’s fuse continues to burn even when players try to breathe and gather spending cash.

Finally, players can increase their base spending value by paying coins and discarding from the deck—and the hiss of the fuse grows louder yet. The base value covers a significant portion of the game’s spending, but coins are needed to fill gaps and for certain ancillary expenses like landing on occupied rondel spaces.

Every action changes the distribution of icons in the discard pile and moves the game towards its denouement. Despite staring down a deck of 80-some odd cards at the beginning, I was surprised at how quickly the pile diminished. Even our first play only lasted around an hour. I was also surprised at how easily the dynamite count can get lost in the shuffle. You really have to pay attention if you want to generate a specific explosive result.

Roughly half of the deck consists of Fluctuation cards that hold no stock value but unleash changes to the market and/or special actions. The deck sits face-up, which also adds a bit of precious prescience to the equation. Play is rhythmic for the most part, buying and selling, increasing capacity, buying and selling, etc. until the end.

The surprise

Perepau Llistosella has designed several titles for Looping’s 19xx series. I’ve not yet played his others, but 1920 is a solid first exposure. Pedro Soto is the illustrator for the entire series if I’m not mistaken. A commodities game set a century ago does not garner hope for creative artistic choices, but there is no question that the series aesthetic is consistent here, even if it leans on the drab side.

I think that drab side lowered my expectations a bit. But I was super thankful to find that the gameplay has more vibrance just beneath the surface and totally delivered as a fascinating title in the Looping series.

I don’t typically run toward speculation and stock-based games, but I am glad to have 1920 around for several reasons. It is, functionally, exactly what you would expect of a stock-trading game. Balancing the voices in your head that cry, “Gather! Hoard!” with those that say “Unload! Be a mover and a shaker!” is the heart of the genre. But there are standout features.

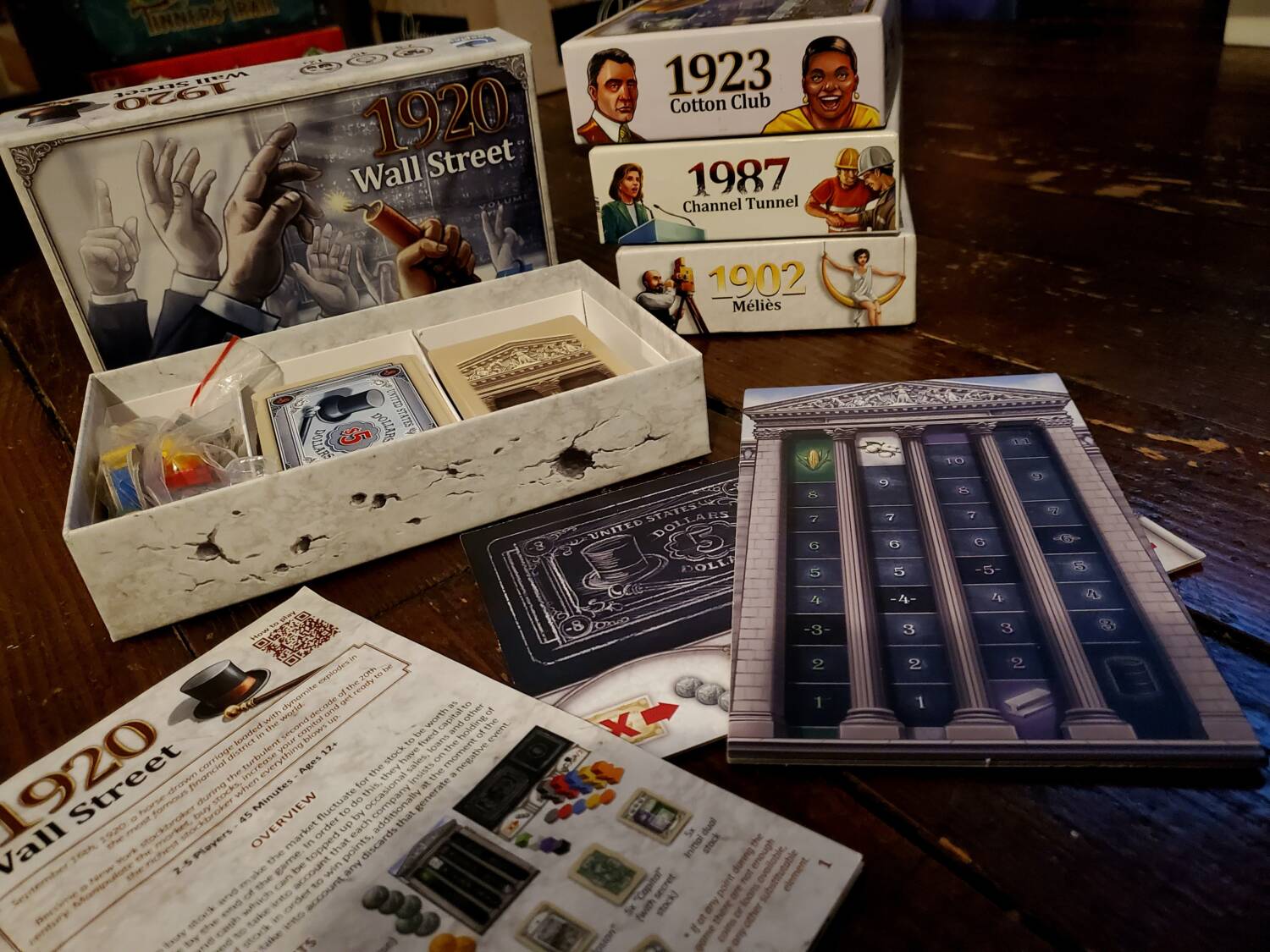

First, I do love the small box. This game is the physical size of The Crew, Cartographers, Arboretum, or any of a host of card games. Any time I can fill a genre in my collection without taking up space, I’m happy.

Second, the historical quirk scratches where I itch. I sometimes feel like an outlier, but I would rather play a game that takes its setting/theme/context seriously, even if it throws an obvious wrench into the ruleset. I find myself celebrating hiccups when they come as a result of faithful narrative. I love Obsession for its providential inconsistencies, Pessoa for bizarre tightness to embody a man with voices in his head, and Surrealist Dinner Party for its awkward self-consciousness and questionable entrance and exit strategies.

Some of those games boast a gorgeous aesthetic that, frankly, 1920 lacks. But the narrative quirks definitely overcome any misgivings from the game’s appearance. (You’ll have to forgive my tendency to judge a game by its cover.)

The boom

At the end of the day, 1920 Wall Street is an interesting stock trader. It’s probably my favorite in a category that’s not my favorite, for what that’s worth. For the time being, it will stick around. I’ll try to introduce it to folks that might enjoy the narrative bonus. Of my original set of Looping titles, this one took the longest to table, but regrettably so—I’ve enjoyed it. It’s not exactly a carriage of dynamite, but there’s a volatility that I’m happy to investigate further.

As I work my way through the Looping 19xx series, I’m keeping my thoughts in order with a ranking. I will provide that ranking with each review:

- 1987 Channel Tunnel

- 1923 Cotton Club

- 1920 Wall Street

- 1902 Méliès