Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I am one of many who have come to know the story of George Méliès through the pencil drawings of Brian Selznick. The Invention of Hugo Cabret is a magnificently illustrated story of belonging and purpose that surrounds the trials and triumphs of the French filmmaker. You can bet it’s a compelling story if it rouses Martin Scorcese to create a three-hour family masterpiece—Hugo sits firmly as my third favorite movie of all time.

Before I knew about the 19xx series of titles from Looping Games, I had marked 1902 Méliès as my most anticipated release at 2023’s SPIEL in Essen. Given my relationship with the subject matter, I never hesitated in wanting to join Méliès here in creating his best known film, A Trip to the Moon. When four games from the series arrived at my door, I set the others aside and opened 1902 like a kid on Christmas. Anticipation always pays off, right?

Imagine my horror when I realized the board wasn’t in the box. I was ready to fire off an email when I thought it best to open the rest of the boxes to see if anything else was lost in the shuffle. Much like my rulebook laugh with 1987 Channel Tunnel, I couldn’t help but chuckle when I found a 1902 board in my 1920 Wall Street box. This series definitely keeps me on my emotional toes.

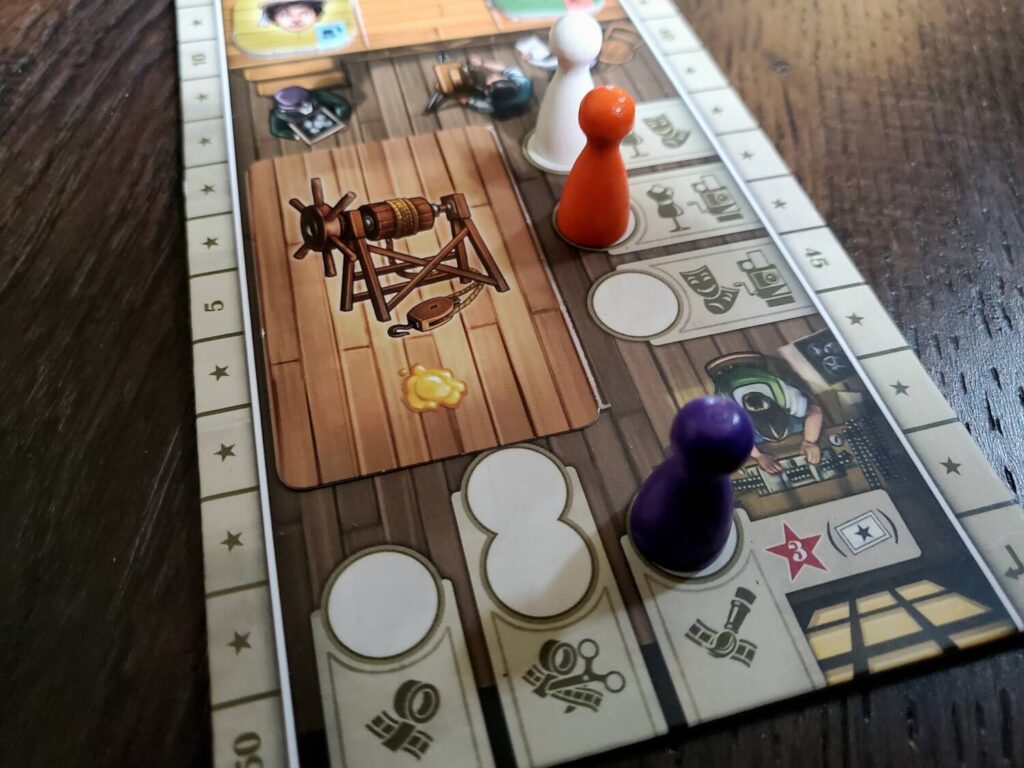

1902 utilizes worker placement, the bumping variety, to simulate the rigors of the three months Méliès took to create the 14-minute menagerie. Players compete to build sets, costume and position actors, film and sequence scenes, and color the finished product en route to victory.

Mott the Hoople and the Game of Life

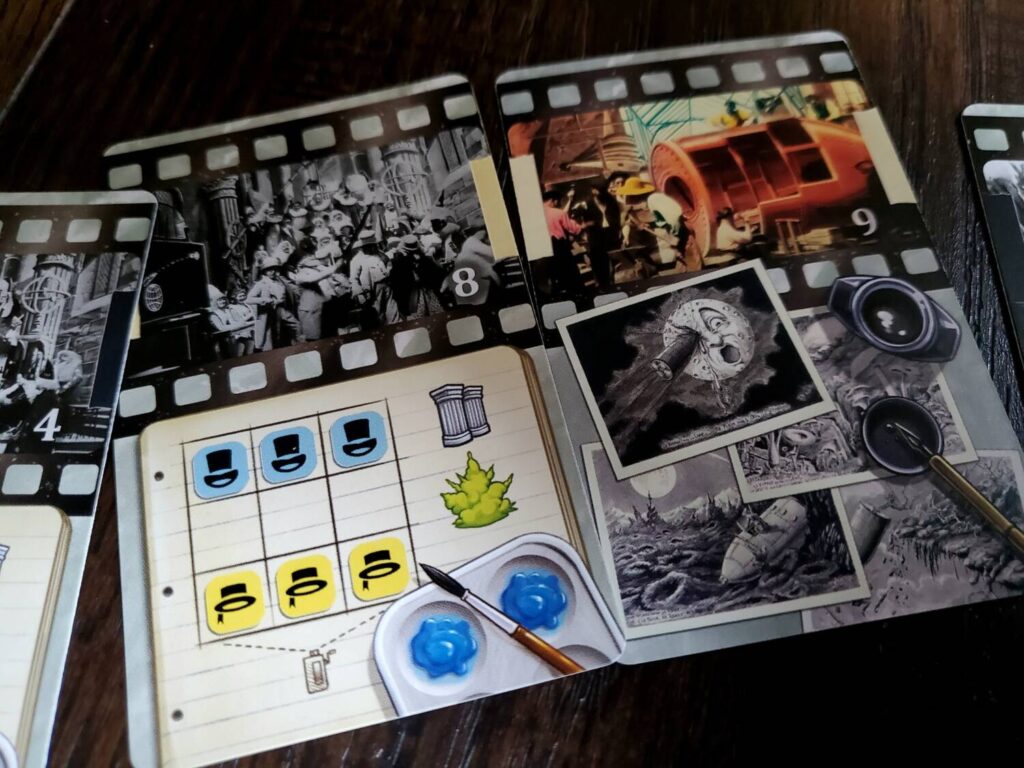

Players send 1980s-era pawns about Méliès’s Star Studio, the greenhouse facility where he brought his dreams to life. The flow of the game is all about establishing the right board state to film one of 42 numbered scenes. Each card requires a Set, selected via a rondel, and a Special Effect, enacted by a card.

A 3×3 grid represents the stage. The six actor tokens are double-sided costumed characters. Players can spend turns flipping and moving these tokens in an attempt to position them according to the preference on a scene card. Perfection is not required, but more actor tokens in place means more points for filming the scene. In fact, when the scene is Filmed, the only earned points come via the actors.

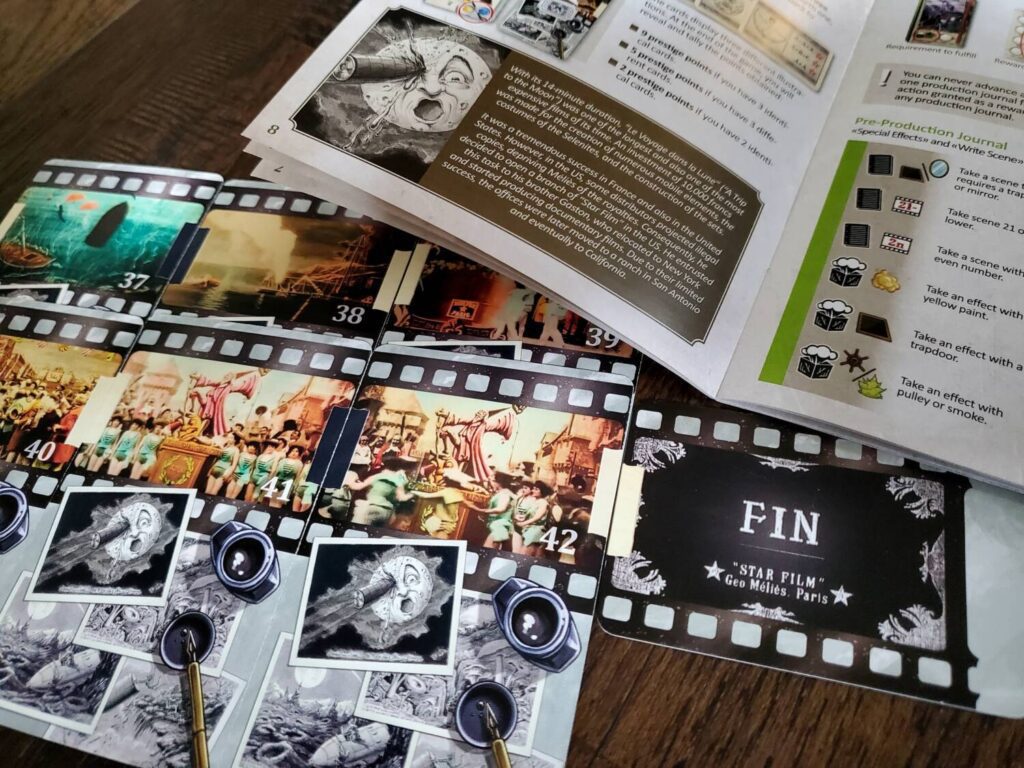

In the cutting and coloring room, players splice filmed scenes into ascending sequences. Gaps are fine—it is a work in progress, after all. Splicing requires the tape depicted on each side to match from card to card. At the game’s end, each scene in a sequence will score points equal to the number of cards in that sequence (max five). Building a sequence of five of your own cards, to the exclusion of everyone else at the table? Twenty-five points of pioneering cinematic gold.

Andy Kaufmann in the wrestling match

Of course, there is always the nuclear option. By using both of those old-school pawns you can cut the tie between two scenes and tape either another card, or even another sequence, in its place, honoring the five card maximum. Of course, this action cannot be haphazard or purely vindictive. The effort must also improve the scene. The pasted sequence must close the number gap, advancing the film toward its final form. That might require planning and a bit of fortunate timing.

Méliès had a team of ladies who worked to hand-paint every frame of his movies in an assembly line formation. The Special Effect cards also depict a blotch of aniline dye in red, yellow, or blue. Players spend these cards to color scenes that have already been filmed. Sequence doesn’t really matter here, nor does card ownership. The player with the paint receives points, and if the scene card happens to belong to someone else, they receive a stock card as compensation.

Monopoly, 21, Checkers, and Chess

Right, the Stock cards. Winning the award for the most corrective mechanic in a film game, Stock cards exist primarily to prevent redundancy in the Set rondel. They are awarded for clockwise movement as an incentive to resist the urge to act like a table of bickering kindergarteners moving the rondel back and forth in hopes of narrow-mindedly filming one scene. Players only keep three of these cards and score based on the combination of images at the end of the game. More importantly, players hang on to their dignity.

For a hint of euro spice, three journals provide tracks with bonuses that are unleashed when a player takes a specific action during the game. Filming a scene with a wizard? Sequencing using light tape? Drawing mirrors or trap-doors as Special Effects? These sorts of actions might trigger movement on the track, granting one-off bonus actions or generous ongoing effects. The journals make you want to do things and contribute to some satisfying turns.

The end comes when one player films their sixth scene.

Mister Fred Blassie in a breakfast mess

The first several turns in 1902 feel like dancing knee-deep in Jell-O. One player moves the Set rondel only to watch the next player move it elsewhere. One player flips Actor tiles and moves them into place only to watch another player crank out a different iteration. Feelings of futility put the entire game in jeopardy before players reclaim their pawns for the first time.

But at some point, the Jell-O breaks down and the game opens up. Players start collecting a variety of Scene cards to better adapt to the changing rondel. They likewise amass Special Effects to be ready to film or color a scene at a moment’s notice. The frustration is that these cards come one at a time in a game with only two pawns (three in the two-player affair) potentially available. I feel the same drag every time I play Asking for Trobils. The pawn bumping mechanism creates a burst of speed every now and again, but the early game is the kind of tedious that makes you want to house-rule something for a boost. Thankfully it builds momentum toward a more active and invested finish.

By mid-game, the table really starts to look like Méliès’s cutting room floor. Eight, ten, or sixteen scenes are scattered about, some in sequence, others not. Some are colored, others are not. Side note: you’re going to want to bring your largest table for this one. 1902 is lanky and its many cards sprawl out over every square inch you have, and then some. In addition to laying out the game setup, you’ll be sliding cards left and right as you create sequences, cut them again, and make them better. Every square inch helps.

Let’s play Twister, let’s play Risk

As I’ve come to expect from Looping titles, design decisions align with the historicity of the game’s narrative. The rules contain a hodgepodge of historical notes and a biography of Mr. Méliès to build the mood. Sometimes the good sense of the game is maddening. It makes sense, for example, that the Filming action comes with last-minute adjustments to actors and costumes. It would be great from a mechanical standpoint if movement on the Set rondel were possible, too. But that just wouldn’t match reality. Sets are more labor-intensive and therefore require additional—and occasionally obstructive—preparations.

1902 is wholly tactical. The collection of cards is not deeply driven by long-sighted strategy outside of looking for cards to enhance a particular numerical sequence. The board state changes on nearly every turn, throttling the motivation to develop settled plans. Instead, a player’s materials—which are all in plain view at all times—are all about preparedness. There’s room for blind hope, but it’s best to just stock the pantry so you can cook whatever the momentary appetite requires. Trying to collect and complete one scene at a time might result in throwing furniture out the window. Instead, the hour is defined by constant adaptability and the willingness to just grab a card because you know you’ll inevitably need one like it when the mood swings.

But the game does sing when the occasional combo comes together. It feels good when the stars align, actors take their places on a good set, and you spot the best last-minute adjustment to land a five-point scene. It feels even better if that scene triggers movement in the production journal and your turn becomes a combo of cinematic joy. I’d imagine Méliès himself had days when everything just worked to go with the days when he wanted to crawl through a trapdoor and hide.

Splicing is an overload at first—it’s hard to be okay with some of the disjointed configurations—but I love the idea of wrestling for the most lucrative combinations. The looming endgame forces efficiency to the forefront. And despite the fact that it’s easy to reduce the cards to their icons, the theme shines.

I’ll see you in heaven if you make the list

As I look back over my words, I realize I’ve painted with an occasionally abrasive brush. But here’s the thing. I really like 1902. I think the gold here is most effectively mined when three or four players are familiar with the ebb and flow. Once everyone realizes where turns need to be snappy (nabbing cards) and where they permit time (planning combos in the production journals), there is a satisfying rhythm.

I don’t always explain my ratings, but here I feel I must. Know this about me: I try very hard across all my reviews to give only whole-number ratings. I like the tension and eventual clarity of deciding whether a game is one or the other without caving in to the half-star. 1902 Méliès is not a 3.5-star game. There are some that will balk at the frustrations and give it three stars, recognizing the mechanics as interesting, but ultimately settling without any great enthusiasm. Then there are others, myself included, who will give it four stars, believing that the mechanics and theme will ultimately prove genuine and rewarding despite the awkwardness of the initial greeting. I’m not sure there’s a middle ground. The game is too assertive in its identity to equivocate. And I like it.

Eloi Pujadas (Zoom Barcelona) and Ferran Renalias (Lacrimosa) teamed up recently to design Battle of Versailles with some success. 1902 similarly flies slightly under the radar, but I believe their work here is worth celebrating as well.

All the Looping hallmarks are present: smaller box size, middling components, immersive theme, informative ruleset, invested mechanics, and reasonable play time. Though I sound like a broken record when I say it: if you’re into some 20th-century phenomenon or event, it’s worth seeing if Looping has a title to match. Because of the mixed reactions I’ve encountered, I’m not sure 1902 Méliès will see the table most among its 19xx peers, but it’s not leaving my collection. In fact, the next time we sit down to watch Hugo, you know what I’ll recommend as soon as the end credits roll.

As I work my way through the Looping 19xx series, I’m keeping my thoughts in order with a ranking. I will provide that ranking with each review:

- 1987 Channel Tunnel

- 1923 Cotton Club

- 1902 Méliès

Both ‘Hugo’ and that eternally classic of the silent film era are favorites. This sounds like it would be a lot of fun!