For over a decade the Evolution series of games have been taking the tabletop world by storm, providing players with compelling gameplay and a subtle education in biology. As the series goes from strength to strength with the upcoming release of Evolution: New World, Andrew Holmes chats with Dr. Dmitry Knorre of Moscow State University, the biologist and designer behind the series.

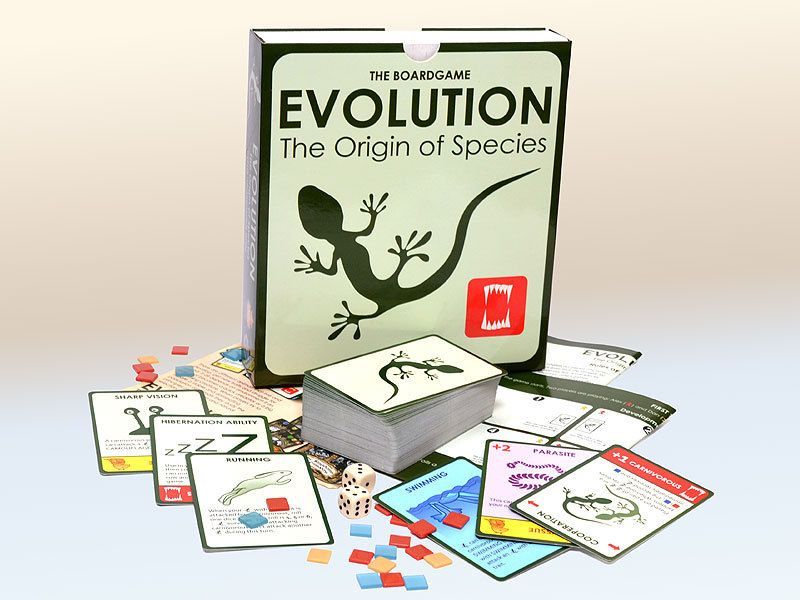

Thank you so much for agreeing to talk with us Dmitry. Can you tell me about the origins of the original game Evolution: The Origin of Species? Did you already have experience designing board games or was this your first design?

Dmitry Knorre: My story about the origin of Evolution: The Origin of Species is rather simple. It is always difficult to choose a birthday present for friends. Thus, once I decided to make a self-made board game, it was a plan on which I began to think strongly in advance. As far as I am a fanatic biologist, I started to think about the game on animal diversity and interaction. I believe that biology is way more amazing and diverse than (e.g.) fantasy which is a more traditional topic of board games.

I played the game over and over in my mind and ended up with a mechanic that looked functional. It was just some basic rules: random resources each turn and a few basic cards: animals, carnivores that can eat animals instead of the resource, fat-tissue to accumulate the resource, large-weight to avoid the carnivores, maybe 1-2 else. Then, I gradually increased the number of traits (cards types) in the game. I treated the ideas of the cards as we treat the scientific hypothesis to explain an observation. It is convenient to suggest as many explanations as possible, then select the most simple and try to test them experimentally. In this case, it was not an experiment but replaying the game in my mind with a different set of cards/animal traits. Finally, I made two copies and used them as a birthday present for my friends.

Next, at one of the birthday parties Sergey Machin, who had experience in board game publishing, suggested trying to publish it. After this, we replayed the game multiple times (about a hundred?) and Sergey suggested many improvements. It was some kind of friendly tug of war: Sergey was experienced in board games and tried to implement some useful geek tricks. I was trying to preserve the connection of the game rules to biology. Thus, regarding the second question, I had no experience in board game design, maybe only in very childhood. Approximately after a year of regular testings, we published a small number of the game. But surprisingly, the game had “shot”, despite my minimalistic illustrations and unusual theme for board games.

You mention it was an unusual theme when the game was first published in 2010 but the last few years have seen a whole spate of games themed around evolution, from Darwin’s Journey and Darwin’s Choice to On the Origin of Species and Genotype. Do you think gamers are more open to unusual themes these days and how does it feel to have (along with Dominant Species released in the same year) led the charge for evolution and natural world-themed games?

DK: Since I’m not a real board game geek, I have a pretty poor experience with biology-related board games apart from Evolution: Origin of Species and its re-implementations. A few years after we published Evolution, we tried Pandemic, Pathogenesis, Dominant Species, and I really like them all. While I barely remember the rules now, I still got the impression that the connection between the game mechanics and topic were implemented very well. So, yes. I would say that fantasy/sci-fi thematic are too overcrowded now and the unusual theme takes its attention.

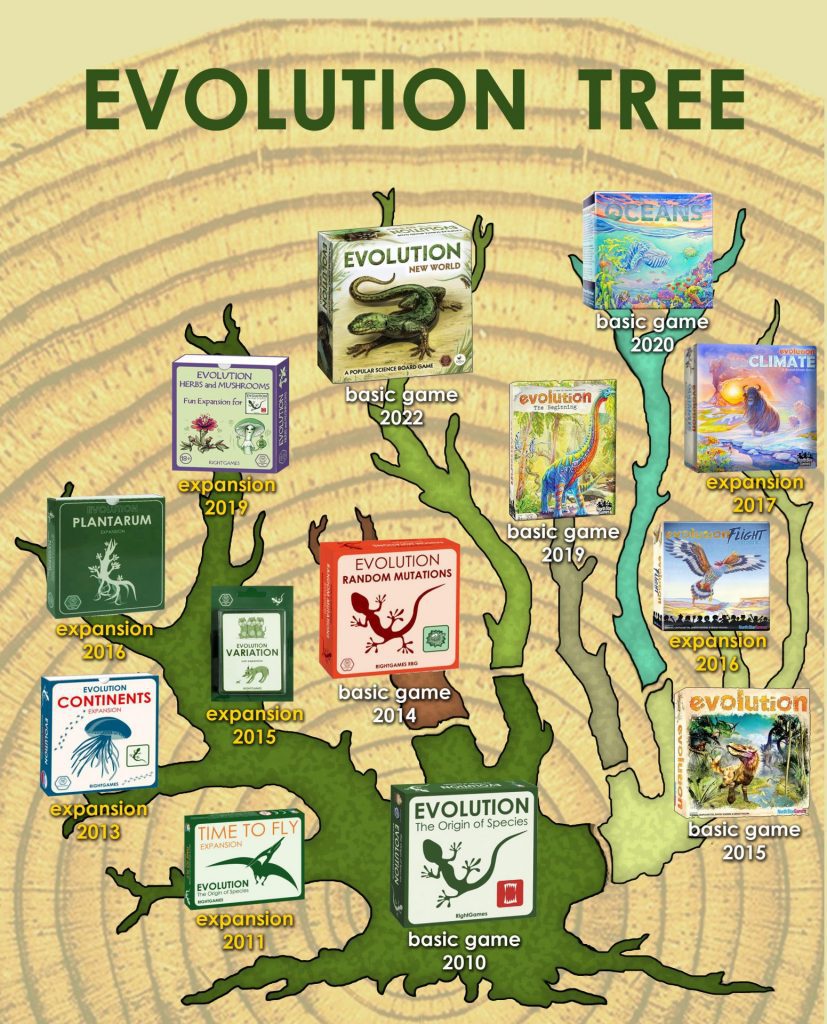

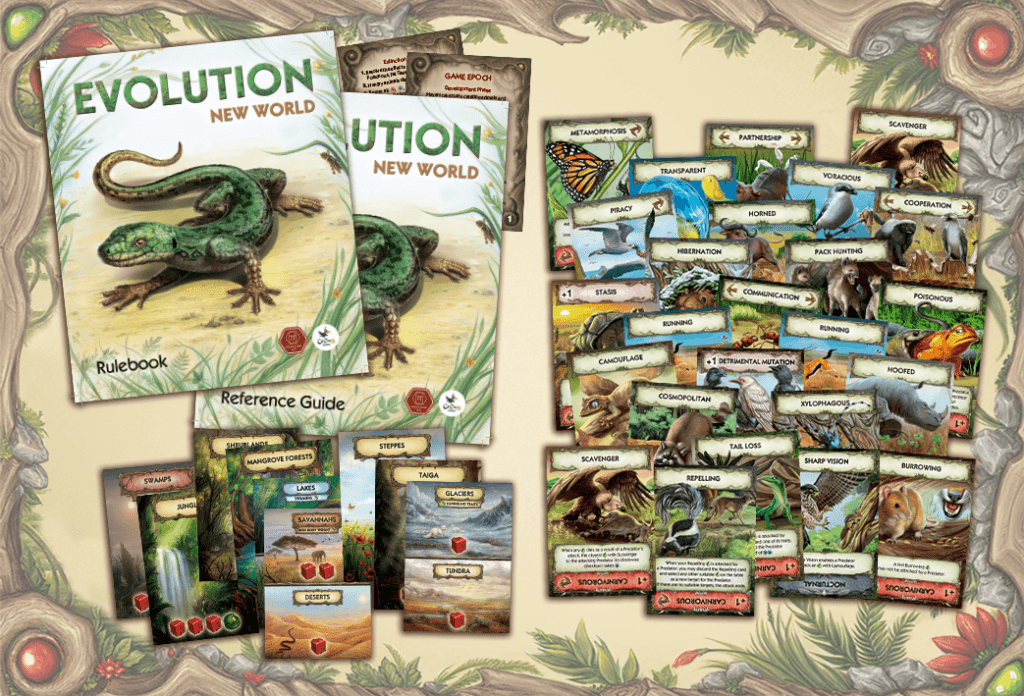

I’m interested in the divergent evolution of the descendants of Evolution: The Origin of Species – over the past decade there have been 4 major expansions, the stand-alone game Random Mutations and now Evolution: New World, whilst a whole second series of games have branched off through North Star Games starting with the 2014 release Evolution and its 2 major expansions, as well as the stand alone games Evolution: The Beginning, Oceans and the upcoming Nature. Clearly your original game struck a chord with both its theme and mechanics, how did the different series come about and how involved have you been in the various implementations?

DK: At the moment when Evolution: The Origin of Species was first published I already had some ideas of additional traits. These ideas were implemented in Evolution: Time to Fly, thus I consider Evolution: The Origin of Species and this first add-on as a single game. Meanwhile, Evolution: Continents was more like a development of the original game. The same I can say about two additional expansions: Evolution: Variation Mini-Expansion (2015) and Evolution: Plantarum (2016). It should be mentioned that adding a single additional trait to the game doubles the possible combinations of the cards (traits on an animal), therefore, the later expansions provided a burst in variability and, on the negative side, some rules quirks. It took a lot of time to test and edit the rules to minimize these inconsistencies.

In all the aforementioned games I drafted the concept and the rules. I like to consider myself as the author and Sergey Machin, who is also listed as an author on the box, as the editor. This reflects our roles in game development rather than relative contributions that are very hard to untangle. I also have to acknowledge many other people who contributed to the game. My family and friends helped me to test the game. Moreover, the colleagues who assisted with explanations of game situations. A good example is the following case: an animal that is attacked by a carnivore can remove the parasite using the trait “tail loss”. I struggled to find a biological representation of this game situation, however, my friend, a leading ornithologist in Moscow State University, Pavel Kvartalny found one explanation. He told me that Kea (the parrots from New Zealand) first ate parasites from the body of sheep but later, when the farmers get rid of the parasites, switched to attacking the sheep. I find it is very insightful to think about real animals representing game trait combinations.

A special case was the Evolution: Random Mutations. It is a stand-alone game that fixes one of the main biological ‘bugs’ of the original game: non-random trait assignment and the absence of negative traits. The overwhelming majority of the mutations are deleterious and it is not correct to consider evolution as continuous improvements. Given that the game became popular in biology classes, I considered it important to illustrate better these concepts and proposed to publish the game Evolution: Random Mutations. Although it appeared somewhat random (not surprising given the title), it was still fun and some people preferred it over the original game.

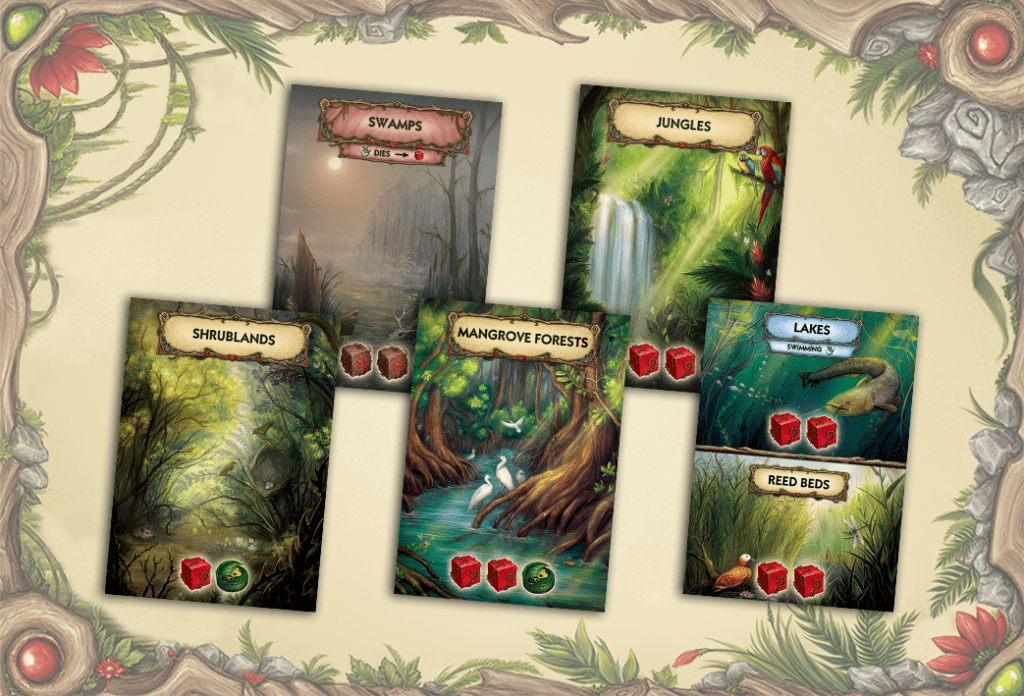

Later on, Fedor Myachin and Sergey Machin reworked the game by combining all expansions in a single well-illustrated game: Evolution: New World, which is on Kickstarter at the moment [and check out Meeple Mountain’s review here]. In this game the mechanics are quite similar to the original game, however, in contrast to other Russian versions, I did not participate in testing and rules drafting. I also did not participate in designing the fun expansion of the original game Herbs and Mushrooms. A similar situation occurred with the US branch of the reimplementations, but with the difference that Dominic Crapuchettis reworked the original game much stronger than Fedor did. Although I am listed as the author there, I barely played these versions.

Your mention of the Kea reminds me of the Vampire Ground Finches on the Galapagos Islands which used to feed on the parasites of larger birds, such as blue-footed boobies, but switched their behaviour and now feed on their victim’s blood, using their sharp beaks to break the skin. Nature is amazing!

I’ve always felt the game is less about how mutations come about and more about how external forces (other species, the environment, etc.) shape how the traits resulting from those mutations persist or die out. I like the idea that you specifically designed a version of the game to more closely resemble evolutionary processes to help in biology classes. How have your students reacted to the game?

DK: This question is hard to answer because I rarely discuss the game with my students. I usually interact with master degree students, whereas the game is more popular among school and bachelor students. Thus, there are just some fragments of the stories that I know. And most of them are rather about social situations rather than biology. Just occasionally one or another student proposes a new trait or share the photo/story of an incredible trait combination that he/she build during the game.

Whilst you didn’t design it as such, the fact that the game is so popular with school and undergraduate students suggests that it and its subsequent iterations act as excellent forms of science communication.

In the UK there’s a large gap between universities saying they want researchers to get involved with outreach and science communication, and actually valuing outreach and rewarding those researchers who do it. How has Moscow State University reacted to you designing the game and raising public awareness of this area of science?

DK: Personally, I had not gotten feedback from our university, just from some colleagues. However, I know that the game is used during the annual “biology day” festival which is carried out by the biology department and open to the general public.

It was funny for me to find out that in a press release of our research article on fungal resistance to antimycotic drugs I was once introduced as the author of a popular board game, although there is no link between my university profile and the game. This press release was prepared by the Moscow State University press service and it was their initiative to present me as a board game designer as well as a scientist.

Your work is clearly a passion for you, what research are you working on at the moment?

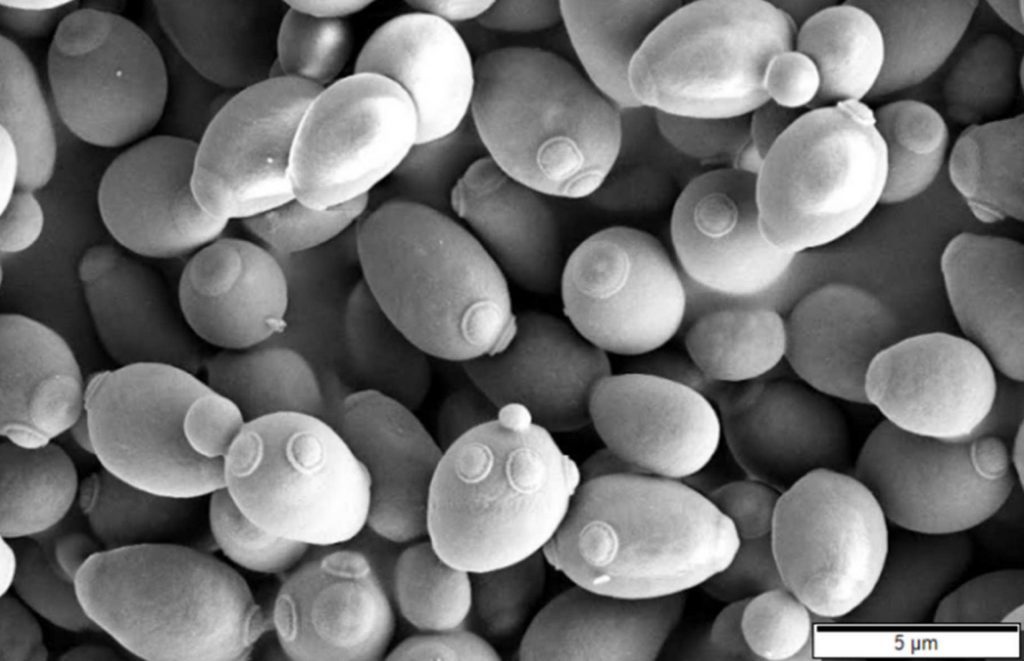

DK: I am a yeast biologist, my research interests are around yeast mitochondria and mechanisms of microbial stress resistance. Currently, I am working on several projects:

(1) First, we are studying mitochondrial heteroplasmy in yeast. Heteroplasmy is a situation when two (or more) different variants of mitochondrial DNA are simultaneously present in one cell. We suggest that there are mechanisms that ensure intracellular selection of mtDNA (remove mtDNA with the deletions). We are now conducting several genetic screenings to identify the components of these mechanisms. Here are my most recent thoughts on this topic can be found here.

(2) Another subject is the mechanisms of yeast drug resistance which are heavily interdependent with mitochondrial metabolism. Maybe you already heard about the problem of increasing antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Fungi are also evolving the resistance to antifungals that are used in clinics or agriculture. We are trying to decipher the principles of fungal drug resistance regulation mechanisms. You can read our recent review on this topic here.

(3) We are also studying the mechanisms of regulated cell death in yeast (which are also connected to mitochondria). The mechanisms of programmed cell death (e.g. apoptosis) are well established in metazoa, but there are still debates about whether yeast has some primitive ‘suicide’ program. My opinion is that they do but the mechanism is not like that in mammals. You can read our most recent experimental paper here.

The reasons single celled organisms may die to benefit their (likely related) neighbours are fascinating, and single celled organisms have evolved behaviours just as interesting as animals (slime mold videos, such as recreating the Tokyo-area railway system, are incredible).

Have you ever been tempted to design a game based on single celled organisms or include any of your own research area in a game?

DK: In fact, while thinking about Evolution: The Origin of Species I often switched from animals to microorganisms. You can imagine that the carnivorous is some kind of Paramecium, the trait “Running” is a flagella movement, “large body weight” is just microbial cell elongation (you may have a look at a very interesting paper (not ours!) about macrophages which are trying to eat yeast cells). In this paper, the authors showed that yeast cells can form long hyphae to avoid being eaten by macrophages. (Indeed, it is difficult to digest long cell via endocytosis). And the macrophages try to literally break the elongated cell (see the fascinated videos in the supplement).

Moreover, I had another board game idea/draft about the evolution of drug resistance. In this game, players are playing against the microorganisms’ deck which automatically attacks players with new infections. Each time a player uses an antibiotic card, this card augments the microbe deck. Eventually the deck becomes very hard to beat and there are some hard choices for the players to manage the available antibiotics. Unfortunately, I had little time to finalize the rules and the publishers put this proposal down. Maybe I have to try one more time, this all was before the COVID pandemic started.

One of the things I like most about biology is that we’re discovering new things all the time about how organisms adapt to survive in fascinating ways, as with the extending hyphae as you mentioned. Are there any developments in evolution that have arisen over the past decade that you’d really like to include in a game but that you’ve not managed to yet?

DK: Although in biology everything makes sense only in light of evolution, in my opinion, the “Evolution” title does not capture the essence of the game series, I see it more like an ecological arms race. Thus, no, I do not connect recent discoveries on evolution and game development.

However, the game forced me to dig into some literature that is far away from my professional interests. For example, in the game, it is possible that poisonous animals mimic non-poisonous ones. To comment on this situation I had to read some modern reviews about animal mimicry. I educated myself about mimicry and found one explanation: a deadly snake species mimicked another less-deadly but still poisonous snake species. It was presumably because the predators did not survive the encounter with the snakes of the first species and thus did not learn to avoid attacking them. (I was not able to find the reference on this case in my archive, therefore it should be considered only as unverified communication).

I love that you’ve been so thorough in making sure that trait combinations possible in the game can exist in nature. What’s your favourite trait that you’ve included in the games so far?

DK: If I have to choose one trait (card), I would say that it is an angler fish. It is played like an animal card, but if attacked, it counterattacks and devours the attacking animal. However, talking in general I would say that I am more fond of paired traits [traits that affect two adjacent species]. I suggest that one of the important biology concepts that can be illustrated with the game is that an (eco)system with multiple interactions is more productive and stable than one with several monstrous creatures.

That’s such an important take on the games. One of my favourite moments in the games is when new players discover they can create their own small ecosystems of animals within the wider ecosystem of all the players – you can see their appreciation of the game and understanding of the natural world expanding as they play. How has designing the game and living with it for 10 years influenced your own understanding of biology and evolution?

DK: While I admire the progress made in the understanding of evolutionary biology: e.g. in mutational spectrum drivers, genetic burden and fitness landscapes, I am not sure that my understanding of evolutionary processes had changed significantly during the last several years. Anyway, the gap between the game (which is good for starter biology) and modern biology/genetics is too big.

However, as I told earlier, designing the game took some effort to read articles from the scientific fields that are far away from my own. For example, I struggled to select a representative image/organism for a parasite that is deleterious for two host animals. Although many parasitics organisms use multiple hosts, they are usually more damaging to one than to another: e.g. malarian plasmodium hurts humans while being almost neutral to its mosquito vector. As a result, I stuck to a Trematoda which can affect both (or more!) hosts. By the way, I wonder why there are few board games on invertebrate lifecycles that are diverse and easily transformed into interesting game mechanics.

Some Trematoda are especially unpleasant to their vectors – I’m thinking of the flatworms that cause their intermediate snail hosts’ eye stalks to pulsate, drawing the attention of birds who eat the snail and are the flatworm’s primary host. Definitely not great for either host! As you say, there’s so much in biology that could influence game design… but I guess some of it might not be all that palatable for some players to think about!

DK: Yes, Flatworms were also a good candidate for the trait card with the parasite affecting several animals. However, tapeworm was already used in the parasite card of the original game. This is a good illustration of how the ‘evolutionary’ development of the game through its expansions makes some things a little bit tangled at a later point. The new implementation, Evolution: New World, solves such problems by picking the best mechanics from the previous versions.

You talked about how you originally designed Evolution: The Origin of Species for your friends. I believe you’ve got two children, have you designed games for them in a similar way? How do you encourage them to learn through play and what do they think about having a father who’s a scientist and a game designer?

DK: Indeed, I have two children, they are quite grown up. The older one is already a bachelor student in computer science at Moscow State University, while the younger one is still in school and attached to biology.

I did not develop serious board games to play with my children, however, we used to play role-playing (dungeons & dragon) style games. In these games I replaced the combat system with riddles in math, geography, linguistics etc. Each type of monster was a task on a specific discipline. For example, the party had to solve ten very simple calculations in a short time. The timing and the number of mistakes made by the party determined the outcome of the encounter. Given that there was a vivid world with the large map they liked to play this game and tried to do their best to solve the problems. I hope that this helped them to train basic skills in some disciplines.

Another example that comes to mind is an outdoor game on a food chain that we used to play a long time ago with kids at a large party. In that game, the herbivores received victory points for moving between checkpoints. First-level predators ran and hunted them, second-level predators hunted herbivorous and first-level predators… and so on. The rules look very simple, but the mechanics worked fine and we easily adapted it to include adults and children of different ages.

So, I hope that our children were in a good way affected by our propensity to science (my wife is also a biologist, she has PhD in plant physiology) and this attitude at least partially compensated for our tendency to work during the nights and holidays.

Those are some great ideas for incorporating learning into play, I think I’ll be stealing them when my own kids get old enough!

Dmitry, thank you so much for talking with Meeple Mountain, it’s been absolutely fascinating discussing your games and your research with you!

Evolution: New World from publisher Rightgames RBG is currently on Kickstarter here and you can read Meeple Mountain’s review of it here.

Add Comment