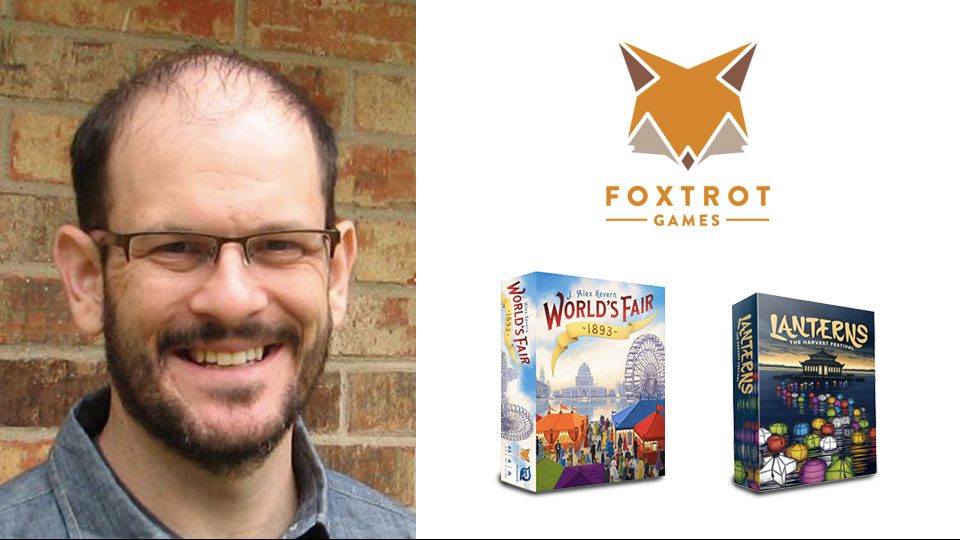

In this edition of Meeple Mountain interviews, we talk to Randy Hoyt of Foxtrot Games about the smash hit Lanterns: The Harvest Festival and the newly released Kickstarter darling World’s Fair 1893. Randy also takes some time to walk us through the publishing of a board game: from finding the right designers to prototyping and playtesting to the design process.

Please join me in thanking Randy for answering all of my questions and give us insight into a hobby we all know and love. Take it away Randy!

Can you tell us a little about your history with board gaming. Did you play boardgames as a kid? Or did you discover the hobby as an adult?

Games have always been a part of my life. I wrote up my “Gaming History” about a year ago, which includes these entries:

- First Game I Loved: Hungry Hungry Hippos

- First Game I Played A Gazillion Times: Yahtzee

- Best Games I Discovered In My Grandparents’ Closet: Mastermind, Risk

- First Game I Preordered: Dvonn (2001)

- First Modern Designer Games: The Settlers of Catan, Carcassonne

I discovered the first few Project Gipf games in college; that was a big inflection point in my gaming history. (I suspect Dvonn was the first game released in the 21st century that I played.) I played individual games in dedicated phases back then: a lot of Dvonn, then a lot of Spades, and then a lot of Texas Hold ‘Em. About 10 years ago, I discovered Catan: that was another big inflection point.

What are your top 5 games right now? Not necessarily of all time, but the ones you’re loving lately.

Here’s another entry from my “Gaming History”:

- Games I’d Drop Almost Anything To Play: Pandemic, 7 Wonders, Coloretto

I’m three-fourths of the way through a Pandemic Legacy campaign with my wife and another couple. Pandemic was already one of my favorite games, and I’ve absolutely loved the campaign mode. I’m planning to get another copy and play it with my son after I finish.

7 Wonders is another one of my favorite games. We haven’t played this one in a while because we’ve been playing Pandemic Legacy with our regular group, but I’m looking forward to getting this game back to the table soon.

Coloretto is such a delightful game. I taught it to some new players earlier this year, and we played seven games in a row.

I’ve been playing a lot of Deus and Bruges lately. I’m fascinated with how differently they approach multi-use cards and managing money plus five different types of resources. I don’t expect either of them to land in my Top 5, but I’ve enjoyed exploring them both quite a bit.

If I recall, you work full time as a web developer. What types of things do you work on?

Yes, I work as a developer for an enterprise software company. The company makes a suite of tools for managing employee schedules and performance. I write all new features in a modern JavaScript framework, though there is some legacy code using JSPs that needs to be maintained. I’ve worked at a wide range of companies over the years: software companies, a large retail website, a digital agency, and a couple of startups.

How did Foxtrot Games come about?

When I was playing the Project Gipf games, I read interviews with the designer (Kris Brum) that got me thinking about game design. I had designed some games as a kid, but that was the first time I really considered that the games I enjoyed had been created by real adult human beings. As my web development career was taking off, working primarily with digital products, I also had a strong desire to create a tangible product.

Years later, my step-brother Tyler Segel suggested we make a board game together. We both loved playing modern games, and we had seen the success that other game designers and game artists were having funding their own creations on Kickstarter. We brainstormed ideas for what would eventually become Relic Expedition: I designed the game mechanisms, and he did the artwork. We raised money on Kickstarter and delivered rewards to backers for that first project 2½ years ago.

I had a vague idea when we started that we might publish games designed and illustrated by other people, but I didn’t really know exactly how all that would work. I have learned a lot in a short amount of time, and it’s been great to partner with some amazingly talented people (game designers, artists, graphic designers, and a rulebook editor) on Lanterns and World’s Fair 1893.

Do you have specific goals for Foxtrot?

I want to make games that people still play 50 years from now. (That was part of the meaning of the name: the foxtrot is over one hundred years old now, and people still dance it.) I know Foxtrot Games is a business with a balance sheet and income statements and all that, but I don’t ever want to lose sight of the goal of making great games that people love.

I don’t currently have very specific business goals. The first goal was to make a board game and learn about the industry, and I did that with Relic Expedition. The second goal was to apply what I learned from that to make a profitable board game, and Lanterns has well exceeded that goal. World’s Fair 1893 was a great third project: it was much bigger in scope (with artwork costing more than double what it did for Lanterns) and has already turned a profit for me. Many people ask me when I’ll be able to quit my day job and make games full-time, and I don’t really have plans to do that any time soon. I love making games, but I’m a little worried about that changing if I need the money from making games to pay my living expenses. But I’m certainly not ruling it out or anything.

In your Twitter profile you list yourself as a Christian. How does your faith impact the choices you make as a game publisher?

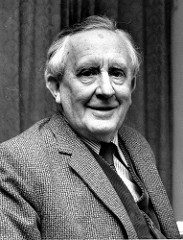

The life and work of J.R.R. Tolkien has greatly influenced my thoughts on creative work and faith. Tolkien wrote, “We make … because we are made … in the image and likeness of a Maker.” Tolkien called his creative work “sub-creation,” creating a secondary world within the primary world of God’s creation, and he saw it as a spiritual act. I don’t know if Tolkien would count board games (especially more abstracted Euro games!) as sub-creation or not, but I certainly do. The goal of such sub-creation, in Tolkien’s work and in the games I publish, is “shared enrichment.” “Both designer and spectator can enter” into this secondary world, and they become “partners in making and in delight.”

I could talk theology and philosophy of art all day, but this perspective has a big impact on the kinds of games I publish: the feel of the mechanisms, the subject matter, the art style, etc. I spend a lot of time thinking about the overall experience the game facilitates. My faith more generally informs what I consider valuable and how I feel I should treat other people, and those in turn inform many of the other choices I make as a game publisher: my contract terms with designers, the level of attention to detail, how I interact with playtesters and customers, etc.

When you started working with Christopher Chung (the designer of Lanterns) did you have any idea the game would go on to receive such critical acclaim and popularity?

I knew the game had a special spark from my very first play. I loved it immediately. I admit that I was a little concerned about how well it would do on Kickstarter. It’s a simple game with a calming theme (and without wild stretch goals or exclusive content), and I was afraid we wouldn’t be able to communicate how rich and how fun it is. I believed it could be successful on Kickstarter if we had great artwork and great reviews, and I worked hard to make those happen. I wasn’t completely surprised the campaign did as well as it did; I really believed it was possible or I wouldn’t have signed the game.

The success since the campaign, though, has exceeded my expectations. I believed that Lanterns was a great game and that a lot of people would love it, so in a way I’m not surprised. But with our first game, I realized I had a lot to learn about marketing games and selling to retail stores after a Kickstarter campaign. Partnering with Renegade Game Studios has played a big part in getting the game out into the market so it could have its best chance at success. It’s so satisfying to see this many people buying the game, sharing pictures, logging plays, and experiencing the enrichment and delight we wanted them to.

How did the deal with Renegade happen?

Scott Gaeta from Renegade backed Lanterns when it was on Kickstarter. (The story I’ve heard is that that he swore out loud when he saw it, wishing he had found it to publish first.) We met at BGG.CON after the campaign, talked shop, and later he reached out to me about co-publishing it. Renegade has provided industry experience, capital, and marketing expertise that have helped Lanterns reach a much wider audience than I could have reached alone. It’s been a great partnership, and I was happy to co-publish World’s Fair 1893 with them in the same way.

I’ve heard rumors recently about an expansion to Lanterns that’s making the unpub rounds. True/false? Can you offer any information about this?

It’s true! We are developing an expansion. Thematically right now players are placing (in addition to lanterns in the water) firework rockets on the platforms to launch into the night sky at the harvest festival. The challenge here is to make an expansion that adds to the game in meaningful ways without losing the simplicity and elegance of the base game. Because Lanterns is such a smooth playing and approachable game, this isn’t a small feat. We had it at Unpub 6 in April, and we’re in the middle of a wave of blind-testing right now. My friend (and Foxtrot Games developer) Charles will be at Origins running playtests, if any of your readers want to check it out.

Could you take moment to give us a basic overview of the process a publisher takes to produce a game? Let’s use your recent successful Kickstarter, World’s Fair 1893, as an example: how long did it take from start to finish, and what all was involved?

It starts with a game designer pitching me a prototype to consider for publication. There are a lot of ways I might find out about a game, but whatever the path I’ll end up playing a prototype. That might be at a convention with the game designer, or they might mail me a prototype to play with my friends. Alex had been working on World’s Fair 1893 for about 9 months when he pitched it to me.

Once I decide to publish a game, I’ll sign a licensing contract with the designer and start working on development. I think of development in two main (but overlapping) parts: game development and product development:

1) Game development involves lots of playtesting, processing feedback, and refining the game to make it the best it can possibly be. I loved the game when I first played it, but Alex and I worked closely together for another 10 months to make some fairly significant changes the theme and to how key mechanisms worked — plus a lot of minor changes to tune everything just right. (Talking to other people in the industry, I get the feeling that 10 months for the game development is longer than typical. Game development on Lanterns, for example, took 4½ months. But I’ve also heard of some companies spending years on this.) We launched the Kickstarter campaign for the game at this point, 19 months after Alex started working on the game

2) Beyond just the development of the game mechanisms, there is a lot of product development. This is the work that most people think of when they think of publishing: selecting components, determining box size, artwork, rulebook, etc. (Originally World’s Fair 1893 had a bag of tokens instead of a deck of cards; changing the components was part of my role as game producer.) I started working with Adam P. McIver on graphic design about 6 months before the Kickstarter campaign (starting with the card frame design) and then with Beth Sobel a month after that (starting with card illustrations). We had a lot of artwork done before the Kickstarter campaign, though Beth continued to create illustrations at a steady pace during and after the campaign. I think she finished the last illustration about 1½ months after the campaign, and we got all the production files (the back of the box, the punchboards, the rulebook, etc.) all done another month after that.

After all that, the game went to production. It took about a month or two to manufacture the games, a month to freight them across the ocean, and then a few weeks to deliver the games to backers. A few weeks after that, we released the game to retail. Altogether, it’s been a little over 2 years from Alex’s first prototype to this retail release. But as much work as all that is, the retail release is just the beginning of the life the game.

You mentioned that you worked directly with Adam and Beth. As a publisher how much input do you have in the art/concept of the games you produce? Is the artist selected primarily by the designer?

Artwork and art direction is usually handled by the publisher. Sometimes a designer will have a direction or an artist in mind, but it’s typically the publisher who hires the artist, pays for the artwork, and sets the direction. (Some publishers work differently, I know, and others may make different arrangements on a case by case basis.) As part of product development, I changed the themes on both Lanterns and World’s Fair 1893, and I chose the new themes along with the direction for the artwork.

How did you decide which designers/games you want to work with?

I wrote a series of blog posts about the top 10 things I consider when I am looking at a submission, and I recommend people take a look at that that full list. But the biggest factor is how much it excites me to play the game and to work on it. When game designers pitch me prototypes, I’ll sign the ones that make my eyes light up and that I can’t stop thinking about. Because I have a full-time job beyond publishing board games, I have to be extremely excited about a game design to spend that much time beyond normal working hours to do all this work.

If you could pick any designer, or artist, to create a game with, who would it be? And why?

Making games is much more collaborative than I expected when I started. I’ve found you can really build a bond, working so closely with people to bring a creative work into being. Making friendships while also making games has been a delightful surprise in this process. I’d work with anyone from Lanterns or from World’s Fair 1893 again. (I think Beth Sobel is the only one from those teams that I haven’t played a game with yet: we’re fixing that at BGG.CON in November!)

I would love to work with Matt Leacock some day: as I mentioned before, Pandemic is one of my favorite games. But there are so many friendly and talented people in the industry, and that translates into a huge list of people that I’m sure it would be a joy to work with. Starting a new working relationship is a little scary, but I realize that working with new people is a great opportunity to grow as a game creator and as a person. I suspect it will always come down to the game: who designed a specific great game I want to publish and what artist’s style fits that game well.

Thanks again to Randy Hoyt for the time he spent in this interview. If you’ve been living under a rock for the past few years, go buy Lanterns: The Harvest Festival. Go buy World’s Fair 1893 too, it’s out in stores now.