Introduction

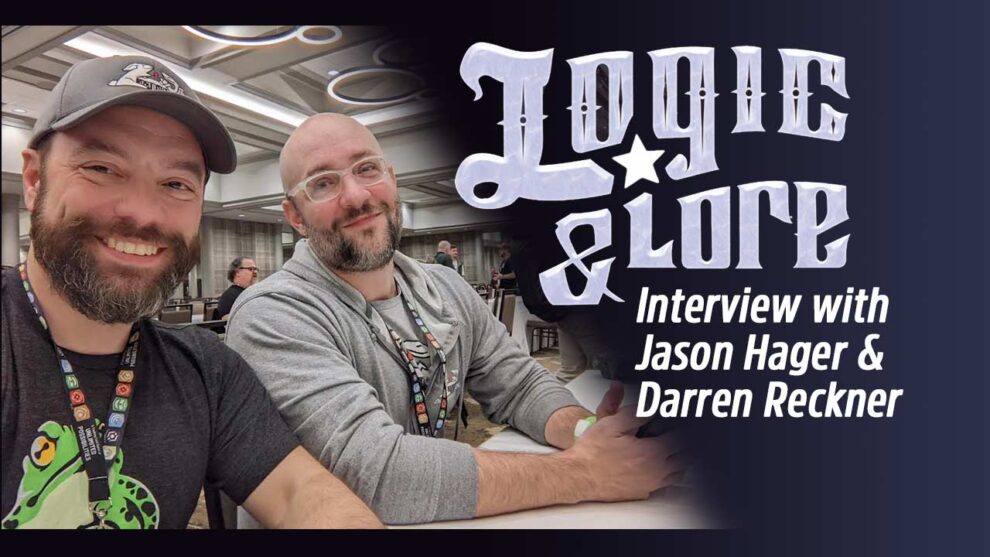

The good folks over at Durdle Games have a Kickstarter for their new game, Logic & Lore. In addition to wanting to learn more about the game, this seemed like a great time to ask the designers (Darren Reckner and Jason Hager) a few questions about themselves.

So, in Meeple Mountain fashion, here are Six Questions with (and about) Darren Reckner and Jason Hager!

Part I: About Durdle Games

Q1: I am sure you have been asked a thousand times how you met and how Durdle Games came to be. So I am going to skip past that and ask the more important question: As a turtle (Jason) and a rabbit (Darren), how do you guys manage to not get on each other’s nerves? Or, assuming you do get on each other’s nerves, how do you get past that to work on interesting games?

Darren: What’s interesting about this comparison is that our playstyles and our design styles are actually polar opposite. Jason is a slow player but has a never ending fountain of ideas when it comes to making new games. I am a quick player that needs time to think about design stuff in my down time. Jason can discuss an idea almost entirely in the mind while I need to start writing stuff down to work through my thoughts.

You can’t work with someone without, at least occasionally, creating friction. A partnership cannot be successful without a few core elements. Respect for the other person is vital. Going into every discussion in good faith is equally important. Egos need to be checked. Understanding that the best idea for a solution may not be your idea. Be willing to do more than your half of the required work. Understanding that what your partner is doing may be different but it is equally important.

Q2: Jason, according to your website, you have an encyclopedic knowledge of gaming mechanisms. That is an interesting bit of phrasing—not games, but gaming mechanisms. What is the best use of a mechanism you have ever seen in a game where the use of that mechanism was not the obvious choice? How about the worst?

Jason: Darren flatters me with that description, but I have played a lot of different types of games! I’m the type of person who brings 30 board games to a family beach trip, just in case.

As for a clever mechanism I admire that wasn’t the obvious choice, I’m going to be a homer and talk about Unmatched, a system we’ve designed content for (but didn’t design the mechanism I’m talking about). In the miniatures-on-a-map skirmish card game, your card draw is tied to when you choose to take a maneuver action (moving around the board). Most card games just opt for the more simple and reliable “draw a card at the start of your turn.” The twist here is that each turn you get two actions, so you are constantly faced with the decision of “do you want to move and draw cards or do you want to stand still and spend cards.” Some turns you draw one card, sometimes two, and sometimes none. I’ve seen similar decision points in a few games, but none execute it this well. I love the tension and downstream effects it causes, like letting the retreating player see more resources and forcing the action to move around the map. A+ stuff.

As for worst, I really didn’t care for the real-time dexterity twist in Butts on Things. It seemed to come out of left field. We had a few injuries (fingers and egos), so we just ignore that rule now.

Q3: Darren, according to your website, you are a word-class expert at bumbling into interesting situations. Given that the word ‘interesting’ is a double edged sword, what would you say was the most advantageous situation you have managed to bumble into? How about the most disadvantageous?

Darren: I’ll start with the worst, way back in the day I was doing some sales work and to try to get in with a potential customer, I decided it might be helpful to attend a local educational group. I wasn’t part of the group so when I showed up I just said I knew so-and-so and they let me in. Did I mention this was healthcare related? That month’s topic was “Wound Care for Guillotine Style Amputations.” Do not google that! There was a presentation with a lot, some might say too many visual examples. I never made that sale.

Probably the best was during my archery dodgeball days. A Wall Street Journal reporter was looking for people to interview about non-traditional fitness routines and they had called our facilities out-of-town owner. A few referrals later they got in contact with our facilities manager who said “I know the guy you need to talk to.” A few weeks later I had done a couple rounds of interviews and there was a WSJ photographer taking my team’s photos for the newspaper. For a couple weeks The Aimbots were the most well known Archery Dodgeball team on the planet. We even got invited to a tournament in Las Vegas. Then a pandemic hit and we faded back to obscurity.

Q4: Your Mission Statement includes the sentence “Be an active and positive presence in the gaming community.” This is a lofty and worthy goal! What, so far, would you say is the contribution to the gaming community that you guys are most proud of?

Darren: We make a point to participate in the local board game design scene. Which does get challenging the more busy we get. Deadlines sometimes keep us from making it to IRL events. Testing and providing feedback to other designers on their designs is important. Those designers aren’t our competition, they are our peers. There is space for all of us to succeed in the industry and by doing events like those we sharpen one anothers skills.

The thing we are most proud of is our family of Durdlers. They are our playtester group that we can reach out to when we are looking for feedback on designs. Everyone contributes at a different level but just having a group where we can post a playing card or ask a question, and get multiple responses in under ten minutes is incredible. They are hands down our greatest competitive advantage. Last year at GenCon we threw a little pre-con game night and we had about 20 people at different tables playing our games, laughing, and having a good time.

Q5: Your Guiding Principles includes the bullet “Perfect balance isn’t as much fun as people think it is.” As someone who has dabbled in game design, I know exactly what you mean! What game, designer, or company do you feel has done the best job at ensuring that this guiding principle is adhered to in the right ways? What game, designer, or company do you think has recently fallen into the balance trap?

Jason: Innovation by Carl Chudyk is a great example of imbalance done right. The combos get so bonkers that you wonder how some cards were even printed. Then you play again and you see a different one. The downside is that occasionally you get some sour grapes from those on the receiving end, but the upside is it feels like the game can do anything, the experience feels varied, and that great stories are being told. “Do you remember that game where I invented Mathematics and became completely unstoppable!?”

As for the balance trap, I know it’s early and this is subjective, but I’ve felt that way with Lorcana so far. Sometimes imbalance is all about perception and promises. And because so many Lorcana cards seem fair, many designs feel “samey” or “safe,” and few feel exceptional. In a card game, especially a TCG, I think you want players to look at a new card and think, “they can’t do that, right? This breaks the game, I’m going to unleash this new menace on my friends.” You ultimately want that promise to spark exploration and for those players to be mostly wrong when the dust settles. But the promise, though, should be grand. I think Lorcana has fallen short for me in that regard, but it’s still early and they have time. (I’m still enjoying it, great game!)

Q6: My final question (before we begin the next part of this interview, questions about your upcoming game Logic & Lore) is going to delve directly into the heart of your relationship with this hobby. What game have you played where you finished a session and immediately thought, “why didn’t we design this one?”

Darren: Robot Quest Arena is the most recent one I played where I could track in my mind the decision points where if Durdle Games had made a slightly different decision we would have ended up with our own version of that game. Congratulations to RQA designers though, they made a very slick, accessible, and fun robot fighting game.

Jason: Just One. I was pretty angry when I finished my first session of it. It’s amazing and so simple. With what seems like an obvious twist in hind-sight, the interstitial “cancel similar words” round is a stroke of genius. All of the sudden players start to segment into clue-giver archetypes like “I give the obscure word that helps narrow it down exactly” and “I give the second-lowest hanging fruit clue,” often organizing themselves in a completely unspoken manner. It also opens up the game to a very wide range of players at the same table, such as folks-leery-of-games, youngsters-that-can-barely-write, and seasoned-gamer-try-hards. They can all engage at the same time within the same system. I’m fuming.

Now that we have some idea as to who these two individuals are, let’s look at their latest game: Logic and Lore! Below you will find six more questions that delve into the thinking for their latest creation!

Part II: About Logic & Lore

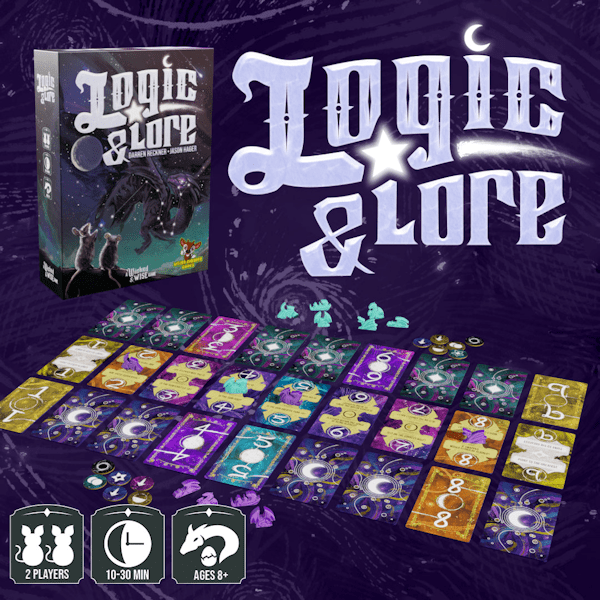

Q1: The initial description I received for this game hooked me right away: Dragons and mice working together to fix the heavens and get the constellations back to where they belong. Since this is an abstract puzzle game, you could have picked just about any sort of theme you wanted to. Walk me through the thought process that birthed this theme and brought it to fruition.

Darren: The initial concept of the game was to order just seven cards and the seven cards would be tied to the phases of the moon. Over time we expanded the theme (and card count) to include celestial bodies in general. Our working title for the game was Constellé, which is a lesser used French word for “starry or sprinkled about”. When Weird Giraffe picked up the title, Carla decided to set the game in the Wicked & Wise world. If you look at the two box covers you can see that they are sister games. The dragons and mice from Wicked & Wise return and are working together to fix the cosmos in Logic & Lore.

Q2: The key to a good puzzle, especially a logic puzzle, is knowing how much information to make available to the puzzle solver. The basic version of the game (Star Light) features four questions that players may ask after selecting two of their cards. The more advanced version of the game (Star Bright) has nine, but they have to be unlocked! How did you determine which four questions had to remain, and the order they needed to be asked? During playtesting, were you looking at some point to use three? Five?

Jason: The development went in the reverse direction. The game was only Star Light for quite a while, and then we expanded the options with Star Bright later – to flex the system’s limits. For Star Light’s core game loop, it was important to us to have the different questions that came with an increasing likelihood of success as the player went down the list, starting with the least likely and ending with a 100% failcase question – ensuring you always make progress on your turn.

So, Alignment and Greatness were must-includes mechanically from the start. Then we found that the two other questions were in the sweet spot of giving you somewhat helpful information while not being overwhelming. I don’t think we ever really went with three or five questions for Star Light since four seemed to shine. Darren will break them down a bit more.

Darren: We went through a lot of questions when assembling the base four questions. But the final set came from here:

- Alignment – players needed the opportunity to lock in correct cards and remove them from their brain space.

- Neighbor – cards 2-8 each have two neighbors. Cards 1 & 9 have a single neighbor. So on average, if all cards are face down you have a slightly less than 25% chance of this question hitting.

- Symmetry – cards 1-9, but not 5, have a single symmetry card. As only a single card can satisfy this requirement it has a lower chance than Neighbor. But when you learn where one of the symmetrical cards aligns, you have by default learned the other and you can position the second card permanently and never Search the Sky on it again.

- Greatest – this one always has an answer. This is important because even new players can track which cards are larger than others and make moves to get closer to the solution each turn.

I can’t recall if we ever looked at more than four or less than four questions for Star Light, we dialed in the base four pretty early and never looked back.

Q3: One of the ways you allow players to ratchet the difficulty of the game is shifting from the basic (Star Light) to the more advanced (Star Bright) version of the rules. This is a wonderful addition to the game! One of the things that you bring up in the rulebook is that the players do not have to be playing the same version of the game! Who came up with this idea!? In playtesting, what sort of issues came up while trying this odd asymmetrical version?

Jason: Well, the first thing to know is that the base system is so simple that it was a delight to try things a hundred different ways. I play half of my games with seasoned-gamer-tryhards and the other half with family, some of whom need to be convinced to play games. Different versions of the game were scratching an itch for different folks. We had people say, “oh, I never want to play the lighter version, the real game is the bright version,” and we had a substantial number of folks state their preference was the exact opposite. Typically I think it’s a good idea to put a stake in the ground for a game and just say “this game wants to be this” and push forward with a singular vision with confidence. But for this game, we found that giving the option to tailor the play experience to the audience was a net positive. It also gave us a pretty great on-boarding experience where players could get the hang of things in the simpler version and then decide how they want to proceed.

During a pitch of Logic & Lore to a different publisher, they looked at the light version and said, “hmm, that’s fine, pretty neat, but is there any way to have a little meatier gameplay for our advanced audience.” And at that point, we subtly flipped the center row cards to the advanced mode hidden beneath and their eyes LIT up. They wanted to take it home immediately. Years later, even though they didn’t sign the game, we heard that the same publisher still plays the original prototype we gave them.

And to more directly answer your question, we found that creating game asymmetries between players just added to the customization and didn’t drastically break the game, so we leaned in. The base system is surprisingly sturdy.

Q4: The other way you allow players to ratchet the difficulty of the game involves the addition of Black Hole cards. This is very interesting! What was your inspiration for this mechanic? What sort of other options did you play around with before settling upon this one? What sort of issues came up while playtesting this variant?

Jason: The Black Holes came from a couple of design paths we explored. At one point, the game was a HABA-style game with the theme of “The Princess and the Pea.” And in that world, having a single item that you can’t really feel out made a ton of thematic sense. That version then evolved into a version with pieces of layered cake and a single piece of broccoli where you wanted to feed the broccoli to a dog at the end of a table to win. You could only ask about the layers on your cake, so the broccoli always returned a negative answer.

As you play Logic & Lore, you see just how important negative information is within the system. So, giving the game an ultimate source of negative information seemed like a perfect fit. We did notice an issue if we used too many. Using a bunch made it so you just couldn’t trust anything and that you were forced to make giant guesses instead of deducing. We took note whenever games felt like that and pared things back. Uncertainty can be a great way to fuzzy a system and spark excitement, but too much can sour the puzzle and leave your choices feeling listless.

Q5: The cards in my advance copy have a simple beauty that feels otherworldly; well done! However, unless you look carefully at the box, and/or read the intro in the rulebook, there is very little to suggest the idea that dragons are involved, and nothing at all to suggest that mice are. This seems to be a sad oversight, given the theme. Was this a conscious choice, the idea of having no dragons and/or mice on the cards? If so, why? If not, is there a possibility that these creatures will show up in the final product?

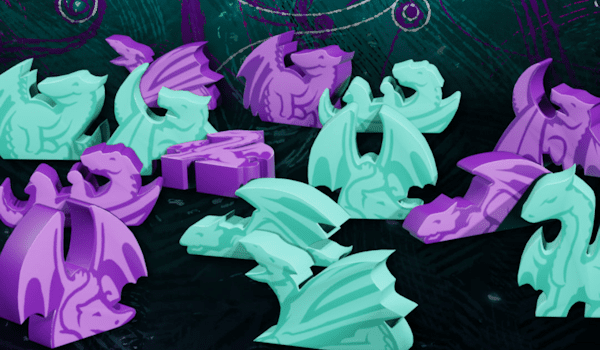

Darren: The dragons do make an appearance in the final product in the form of Dragon-eeples! When playing Star Bright, players claim questions using Dragon-eeples. In the Star Light version players can still use the Dragon-eeples as memory tokens.

Jason: It was fun to design the Dragon meeples! I’m excited to see players move those around the middle and jockey for position among the stars. I’m also really hoping that some folks give the different dragon poses nicknames.

We decided on this level of theme with a willingness to be flexible and listen to the backers. The game is abstract at its core. And for abstract games there seems to be a fine line between providing enough whimsy and delight with the theme versus shoehorning too much in and getting eyerolls (or worse, causing a distraction). I expect there will be a splash more theme as we move toward the final version. I know I’d love a chance to paint a few more of those cute mice!

Q6: Finally, this is a question I have to ask (it is codified into law, ever since the start of the Euro-invasion of board games). Do you see this as a game that could get expansions? If so, what sort of things do you think could be added to the game? If not, do you see this as a flaw in the design, or more as an indication that the game is just where it needs to be? Perhaps it means something else?

Jason: There is a lot of design space here to play around with. We have a lot of ideas and would love to explore them!

Darren: We always felt that Logic & Lore is a game that really thrives being a simple, small box experience. However, there are some other ways to play that require a minimal amount of additional components. A single card and a few sentences of rules can create a very different game experience. So yes, there has been some time and effort put into potential additional content for the game. If the appetite is there for more Logic & Lore we could see that being in the stars.

Conclusion

I would like to thank Darren and Jason for putting up with the whimsy of my questions. I received an advance copy of the game; it is quite fun and clever. Check out my full review.

Add Comment