These days there’s a wide spectrum of board game themes beyond the stereotypical fantasy, farming and trading tropes. Just picking a single letter gamers can be crusaders, cafes, cells, chromosomes, chemists, coppers, cultures, clustering corals, creeping criminals, colonising corporations, cat collectors, cosmic constructors, and chroniclers of crime. Crumbs, cor and crikey!

The hobby has also seen success for games with more thought-provoking themes. Spirit Island tackles issues of colonisation from the perspective of the indigenous population and their gods. In Freedom: The Underground Railroad, players attempt to free slaves as part of the early United States abolitionist movement. Other historical games enable players to engage with political scandals (Watergate), presidential races (Revolution of 1828), the cold war (Twilight Struggle), and a vast number of real world conflicts from across the ages. Even Pandemic’s global infections are inescapably relevant given current events.

Exploring the Personal

Closer to home are games that address a spectrum of personal and intimate moments. Role playing games (RPGs) are particularly innovative for such stories. Star Crossed, by Alex Roberts, explores the interactions between characters that are overwhelmingly attracted to one another but shouldn’t act on their impulses. Emily Care Boss’ Romance Trilogy (Breaking the Ice, Shooting the Moon, and Under My Skin) covers a raft of relationships, from a couple’s first dates through to love triangles and various polygonal shapes beyond. And for those missing the fantastical, Avery Alder’s Monsterhearts dives into the relationships between teenage monsters and is widely commended for exploring sexuality and LGBTQ+ issues.

Board games lag somewhat behind. The abstract but intimate …and then, we held hands. has players trying to reach an emotional balance without communicating verbally. Consentacle is a cooperative card game in which two players try to act out a (consensual) sexual encounter between a human and a tentacled alien, building trust between their characters and, ultimately, reaching mutual satisfaction.

2017’s Fog of Love is the game that has perhaps moved board games forward the furthest. Players are two halves of a couple, each with their own agendas and interests. The game takes place around a series of decision points, presenting players with a question and asking them to balance their own character’s needs against the needs of the relationship.

(True to life, all three games about sustaining relationships revolve around communication).

Tabletop games are also branching out beyond relationships. Notably in the last few years we’ve seen board games addressing illness and mental health (Comanauts) as well as death and regret (Holding On: The Troubled Life of Billy Kerr). We truly are in exciting times for those looking for tabletop themes beyond the typical.

The Parental Void

From the fantastical to the mundane it seems that these days there’s a tabletop theme covering just about everything.

Except… Where are all the parents and children?

I don’t mean where are the games for children or parents – there are plenty of suitable options. Here at Meeple Mountain we’ve got suggestions of great board games for younger and older kids, for families and for tired parents, as well as tips for new parents who want to keep playing games once the baby has arrived. I also don’t mean where are the games featuring children – Zombie Kidz Evolution and Stuffed Fables are two great examples.

What I mean is that given how games delve into the various life-changing moments of our existence as humans, where are the games that tackle the challenges of producing and raising a child?

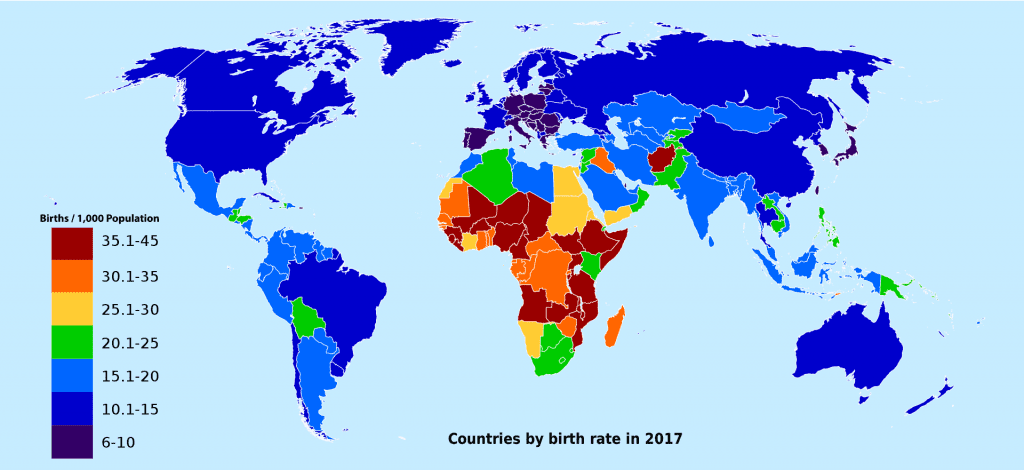

It’s a fundamental aspect of life – according to the UN 130 million babies are born every year. Whilst birth rates have fallen in many richer countries (where the luxury hobby of tabletop gaming dominates), a significant proportion of adults will become parents (sometimes even on purpose) and we all experience some degree of care as a child, regardless of the circumstances of our upbringing. Given its ubiquitousness in our daily lives, it’s strange to think how little represented parenting is in the tabletop landscape.

Importantly, not all of us want to or are able to become parents (naturally, assisted or through adoption/fostering), but that shouldn’t be an obstacle to such games existing – after all, we can’t all be Avengers, vikings or urban planners but around the table we can.

Brushes with Parenting

Of course, tabletop games do brush against parenting on occasion.

The earliest example is The Game of Life, originally created by Milton Bradley in 1869 as The Checkered Game of Life and released in its modern incarnation in 1960. During the game players can gain children that essentially act as monetary bonuses. Older editions even have a space that punishes those without children by forcing them to ‘donate’ money to charity. For The Game of Life, parenthood is the optimal state, bringing financial rewards, pink or blue pegs and very little else.

The most common instance of having a child in a board game involves the mechanism of worker placement. These games use the concept of procreation as a way of giving the players additional workers for more options as the game progresses. Stone Age famously has a mating hut to which players can send two tribe members to gain a third. Uwe Rosenberg’s Agricola and Caverna have Family Growth / Wish for a Child spaces that, curiously, only require a single worker to produce a new addition to the family.

Yet children in worker placement games often have a truncated childhood, sending the newly birthed offspring out to work at the start of the next round. Village takes things a step further by allowing players to activate a marriage space, immediately producing a useable worker offspring in your farmyard for that round. That said, Village takes many things that bit further – you’re later able to kill off the same progeny for points

As an aside, there are plenty of games involving animal breeding, with the baby animals providing points and/or money (e.g. Zooloretto), gameplay bonuses (e.g. New York Zoo) or even being used to feed your family (e.g. Agricola/Caverna among others).

On a more sweeping scale, and despite its outward appearance of Medieval politics and war, Crusader Kings is all about the dynasties of royal families. Players represent historical houses of Europe, their various family members coming to power, marrying suitable partners and having children that then replace them when they inevitably die (of natural causes or not-so-natural ones). Whilst there’s no actual parenting, much of the game is spent trying to arrange useful marriages and setting your children (and your dynasty as a whole) up for success. Ideally you’ll be seeding the future glory of your dynasty with positive traits such as ‘Honest’ and ‘Strong’, rather than negative traits like ‘Gluttonous’ or ‘Slothful’ that will echo uselessly down the generations like flatulence in a cave.

Attempts at Procreation

A few games take procreation a small step beyond simply producing another worker.

In 2013’s CV each player builds a tableau of cards that represent the achievements of their characters, from jobs and possessions to relationships and children. It’s nicely thematic – having a child requires a relationship and money, bringing you happiness but costing you money each subsequent turn.

Curiously, child cards can be covered with other relationship cards, as if after a while you just put your child in a box in the attic to be brought down later for end game scoring. In fact, if you wish to you can place your child card behind other cards immediately, never paying upkeep or getting any rewards. For some, children are a status thing.

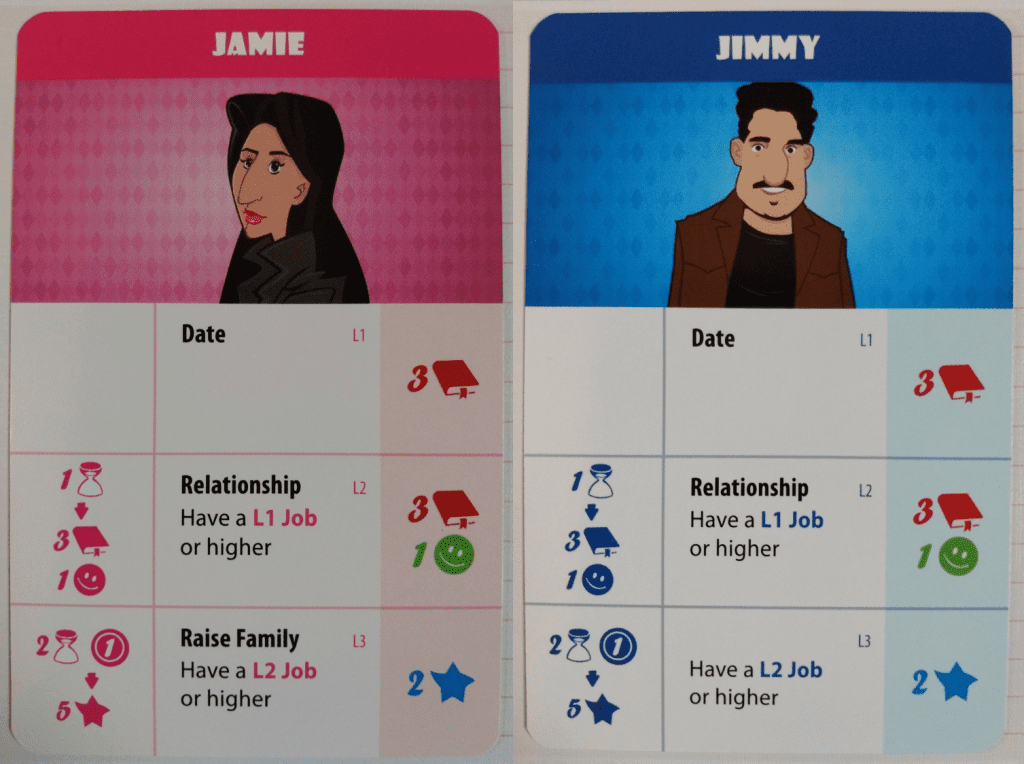

2015’s The Pursuit of Happiness has something similar, allowing players to devote time to selecting an available partner and developing a relationship with them. This upgrading from dating to relationship and then to raising a family can be achieved by meeting the partner’s specific requirements. In return, the player gets some form of reward and ultimately happiness (points).

What distinguishes The Pursuit of Happiness from CV is that relationships and family require upkeep each turn. Players must decide whether to continually invest in the relationship to get the associated rewards or to break it off, gaining stress and losing happiness (the upkeep from relationships can’t just be covered up).

The trouble is that in both CV and The Pursuit of Happiness, relationships and children are treated in much the same way as getting a job, going to a concert or buying a house in the mountains. Ultimately you’re just upgrading your character in different ways.

Advanced Parenting

Finally we come to the tabletop hobby’s two best examples of parenting, only one of which actually involves offspring. Or humans for that matter.

Dungeon Petz is a highly thematic strategy game where players are pet shop owners who rear monster hatchlings to earn awards at judging shows and sell to discerning customers. You’ll buy and sell your monsters and those not bought end up as food for other monsters. Thematically we’re a long way from what you might call parenting, but in terms of caring for a young living creature that develops over time Dungeon Petz is the tabletop high point.

Designer Vlaada Chvátil has stated that he wanted “to create a game where you have to handle entities that behave on their own” and he’s absolutely succeeded. Your monsters need the right kind of food, entertaining, housing suitably and cleaning. They can get sick and die if you don’t look after them properly and they can even hurt their carers. They can, and will, poo. A lot. In many ways this is parenting in all but name, yet those missing thematic pieces are fundamental – you aren’t parents caring for offspring (ultimately they aren’t even your pets) but the owners of needy and fickle property to be purchased, primped and peddled.

To really experience board gaming’s closest attempt at simulating true parenting you’ll need to get a copy of The Pursuit of Happiness’ Experiences expansion. Building on the framework of the base game, the kids in Experiences require upkeep as they develop across the game’s rounds (approximately representing decades of your life), from Newborn to Teenager to Grown-up. When you choose to have a child, the specific needs of the random kid you end up with may require you to change your plans entirely. This isn’t simply paying a resource or some money – in order to nurture your child into adulthood you might have to sacrifice your job, hobbies or treasured items. Fail and your children will still age but you’ll lose happiness.

Whilst still limited, this simple addition to the game makes a lot of thematic sense. Your children grow and develop but you’ll only benefit from their existence if you actually put the time in. What’s more, you don’t know in advance what your child will need to thrive in life and chances are they’ll cost you a lot whether you’re successfully raising them or not. True to life, if you choose to have children in Experiences they’ll come to dominate much of the rest of your game. There’s even a ‘twins’ card that lands you with two of the little darlings…

Reasons for the Absence

Yet none of the above games actually touch on parenting, explore issues around growing up or even begin to cover the potential difficulty in becoming parents in the first place (flipping Caverna’s ‘Wish for a Child’ card to ‘Urgent Wish for a Child’ can resonate especially with those struggling to conceive or carry a baby to term).

It feels like there’s an integral area of our lives that remains completely unexplored by the tabletop hobby. Why?

Perhaps parenting is too mundane, too everyday? People often play games to escape or to experience something different, do they really want to put the kids to bed only to play a game in which they put the kids to bed? But, let’s face it, thematic mundanity is hardly an obstacle to a board game’s success. And it’s not like we don’t enjoy games that involve raising creatures – just look at the success of The Sims, Pokémon or even Tamagotchi.

Perhaps parenting is too complicated? There are so many intertwining factors that go into bringing up a child that maybe it’s too hard to effectively simulate. Yet there are games that play out the various complexities of galactic politics or stock market trading so it seems entirely possible that some entertaining abstraction of parenting could be achieved.

Perhaps it’s all about demographics? Maybe parenting and babies are unlikely to appeal to the stereotypical young male board gamer. Yet the hobby is increasingly diverse and, whilst there remains a long way to go, the needs and interests of gamers are correspondingly broadening. What’s more, young gamers with few dependents frequently become older gamers with families. Conventions now have specific zones for children’s games and some even include crèches or other parent and child areas.

Perhaps the theme of parenting is too ‘real’ – the emotional ties too high, the consequences of failure too steep. In a game about parenting, what does success look like, what qualifies as defeat? We could talk about trying to raise the ‘perfect child’ but how does my idea of an ideal upbringing compare to yours? And would an in-game child that doesn’t match up to a game’s end goals deserve less love and support? It’s easy to focus on the joys of being a parent but childhood and adolescence are full of potential pitfalls, from bullying to accidents. To parent is to worry, do we really want that in board game form? Yet arguably these are complex discussions and stories that the tabletop medium can and should explore.

Whatever the reason for parenting’s absence in the tabletop space there’s so much potential for this untapped thematic area…

Ideas for the Future

Parenting is hard and rewarding, with highs, lows, long-term challenges, little victories and everything in between. It’s the perfect setting to gamify. When I spoke with fellow Meeple Mountain writers Tom Franklin and David McMillan they said:

Tom: “It would be interesting to come up with a Parenting game. I can see lots of forking decisions (work late for more money for your family or go to your kid’s recital) where there’s a constant struggle to balance goals that can never fully be met: Money; Marital Happiness; Child’s Happiness; Personal Fulfilment; etc.”

David: “Parenthood is a convoluted eurogame. You’re developing a human. There’s resource acquisition and management. There’s the feeling of having a million things you want to accomplish and having to prioritize what you actually can accomplish in the time you’re allotted. Parenthood is rife for a game to be made about it.”

Tom and David are right (and they put it far better than I could have done) – the possibility space within the broad theme of parenting is vast. There are so many opportunities for cost-reward dilemmas, so many dynamics where the desires of one party are partially or completely at odds with the desires of the other, and so many specific elements of parenting that games (or even parts of games) could focus on.

Cooperative games could challenge players to work together to raise a child successfully. Competitive games could pit players against one another in the classic parent-offspring conflict, or gamify the idea of competitive parenting (a toxic concept but one that could be explored interestingly in a tabletop setting). With games where parenting isn’t the primary focus, interesting mechanics could appear that are more than simply producing another worker for the next round.

And then there’s the fact that each time you feel like you’ve got a hang of parenting the rules seem to change. Parenting is the perfect theme for a legacy game, an experience where rules can change from game to game and decisions made in one game can affect all subsequent games. Think your group’s Pandemic Legacy playthrough went badly? Just think of the mess your group could make with a tabletop child!

In Conclusion

Looking at the tabletop hobby today it’s hard not to get the impression that having children is bad. Frequently ignored or glossed over, at best having a baby provides the player with a reward for minimal effort whilst at worst babies are cast as the villains (Bears vs. Babies). There’s even 2020’s The Maury Game: You Are Not the Father where you lose if you turn out to be the father.

Despite his excitement at the idea, Tom followed up his thoughts on designing a parenting game with the following statement:

“The only problem with pitching such a game is I’m not sure anyone with kids would really want to play it. Gaming is a great way to escape the world you’re in. Would any parent want to play a game that mimics their own life, only possibly worse?”

He’s got a point. And what would it say about you as a parent if your in-game parenting was better than in real life? There’s already enough stress and self-doubt to being a parent without board games contributing to it!

Yet despite those reservations it still feels like parenting is a space that the tabletop hobby could profitably expand into. I’m not suggesting we need realistic games that provide detailed simulations of parenting, or even that we need games that focus exclusively on parenting. The parents and offspring don’t need to be humans or even the same species. Considering the vast impact parenting has on people’s lives it just feels like a minor module in The Pursuit of Happiness’s second large expansion should not be the best example of including parenting in board games.

Much has changed in the tabletop landscape over the past decade and who knows what developments the rest of the 2020s will birth. Maybe games like Fog of Love and Holding On are the front-runners of a wave of games with more personal themes. Maybe RPGs will lead the way once again to bring parenting into the tabletop space.

What do you think? Should we eagerly anticipate new games where raising children involves more than simply sending them out to work in the next round? Are there examples of parenting in tabletop gaming that we’ve missed? Let us know in the comments below!

Add Comment