The Board Game Soapbox is an ongoing column in which we sound off on all the things in tabletop gaming that grate our cheese, honk our horns, and just plain rub us the wrong way. Anything that makes us feel strongly, we’ll tell you about here.

I have a pet peeve. Okay, okay, I have a lot of pet peeves. If I didn’t, this would be a pretty lacklustre column. Specifically, I have a pet peeve related to board game terminology and the way we talk about complexity in games.

As a hobby, we use two concepts to discuss complexity in games: weight and depth. I’m getting on my soapbox to sound off about (i) why weight is inadequate and harmful, and (ii) how depth is misused. Stick around to the end and you’ll even discover our terminology manifesto for a better board game future!

Weight’s Murky Definition

For those unfamiliar, weight is the term given to BoardGameGeek’s (BGG) complexity rating: the more complex a game is, the heavier it is.

Except… whilst you might assume that the weight scale is synonymous with complexity, BGG defines weight based on one or more of the following attributes: lots of rules, a long playtime, a small amount of luck, a large amount of choices, a large amount of bookkeeping, a high level of difficulty and a requirement for players to have a high level of technical skills.

Some of these criteria make sense: a lot of rules and interactions between those rules is a good indication of a complex game.

Some of the other criteria seem less helpful: one of the ‘technical skills’ listed is the ability to read, which is important for issues of accessibility but less so when considering a game’s complexity. Narrative games often require players to read a lot of text, but the games themselves aren’t always complicated. When you also remember that Monopoly can last an afternoon, you start to feel glad that BGG doesn’t define too many things in your life.

A game’s weight is rated by the users of BGG. Since players have varied levels of experience with tabletop games and everyone’s brain works slightly differently when processing forms of cognitive load, what’s heavy for one user might be considered medium or light by another. This is particularly true when you compare genres and players’ experiences with them: a heavy wargame might be a step up for many people used to heavy economic games, and vice versa.

Peruse the BGG forums and you’ll discover that this level of subjectivity extends to differences of opinion in which specific factors make up weight and how much… um… weight should be given to each factor. Subjectivity isn’t necessarily a problem, but it becomes problematic when everyone is rating weight according to different criteria.

You could base board game weight rating on game mass instead and most games would still end up grouped into the same categories. That big box that makes you break a sweat when getting it off the shelf? A heavy game in more ways than one. Tiny velvety pouch that fits in the pocket of that one pair of uncomfortably tight jeans you own? Light as a feather’s shadow my friend.

Weight’s Harmful Words

Lightness brings us to the second problem with weight and that’s the additional meanings and implications of the words heavy and light, and how BGG’s scale of complexity hampers the way we talk about games.

We may use the word light in an affectionate way but, much like the term ‘filler’, it’s faintly damning. Light implies a lack of substance, something of little consequence, a game that’s easily dismissed, not a game to be taken seriously by the true connoisseur. After all, how many ‘light’ films have won Best Picture at the Oscars?

The terms ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ don’t touch on what those words mean in a wider, thematic way. The Grizzled isn’t a complex game (it’s rated 1.97 out of 5 on BGG’s weight scale) but the grim reality it presents players with is heavier than a sack of spuds. Conversely, Vinhos’ weight is over 4 out of 5 on BGG but it’s hardly Dostoevsky: it’s about wine making (although, in fairness, full-bodied wines are sometimes described as being heavy).

Lightness and heaviness can also be used to describe game feel. Many games have plenty of rules but they evoke a feeling of lightness, a giddy joy that comes from playing in their environment. At the other end of the scale, Scrabble feels weighty despite not being a complex game.

Perhaps this was the original intent of the weight scale, to go beyond mere rules and instead describe game feeling. If so then that intent has failed. In the tabletop hobby weight and complexity are treated as synonyms of one another.

BGG’s weight scale robs us of part of our vocabulary, it’s use of the words ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ creating misunderstandings and causing discrimination against less complex games. Weight as a way of describing complexity is not just unhelpful and inadequate, it’s actively harmful. It’s an arbitrary term promoted far above its limited abilities, an incompetent server who doesn’t just bring you the wrong order but adds in a complimentary dose of salmonella to go with that shake.

The Misuse of Deep

‘Deep’. It’s a ubiquitous term: “Oh, I like Lacerda’s games because they’re always so deep,” or “No, Clank! isn’t very good because it just isn’t deep enough.” It’s an easy word to use because we all think we know what it means. A deep game is one that provides, well, depth. A game that you can learn as much about on the 20th play as you did on the first. That’s all well and good, but there are a lot of different ways a game can achieve depth and the tabletop community seems to have tied it to just one.

Presently, in the hobby, deep is synonymous with complicated. A game rises to the level of ‘deep’ when it includes a lot of rules, a lot of components, and a lot of confusion. Yes, I’m being a touch hyperbolic, here. Confusion isn’t an inherent part of the equation and that’s just my prejudice towards mid-weight games talking, but you get my point. Games like Caverna or A Feast For Odin are labelled ‘deep’ because you can’t even begin to fully grasp them in a single sitting. There are so very many options and intricacies that it will take dedicated study and repetition to grow familiar, then comfortable and finally proficient with them.

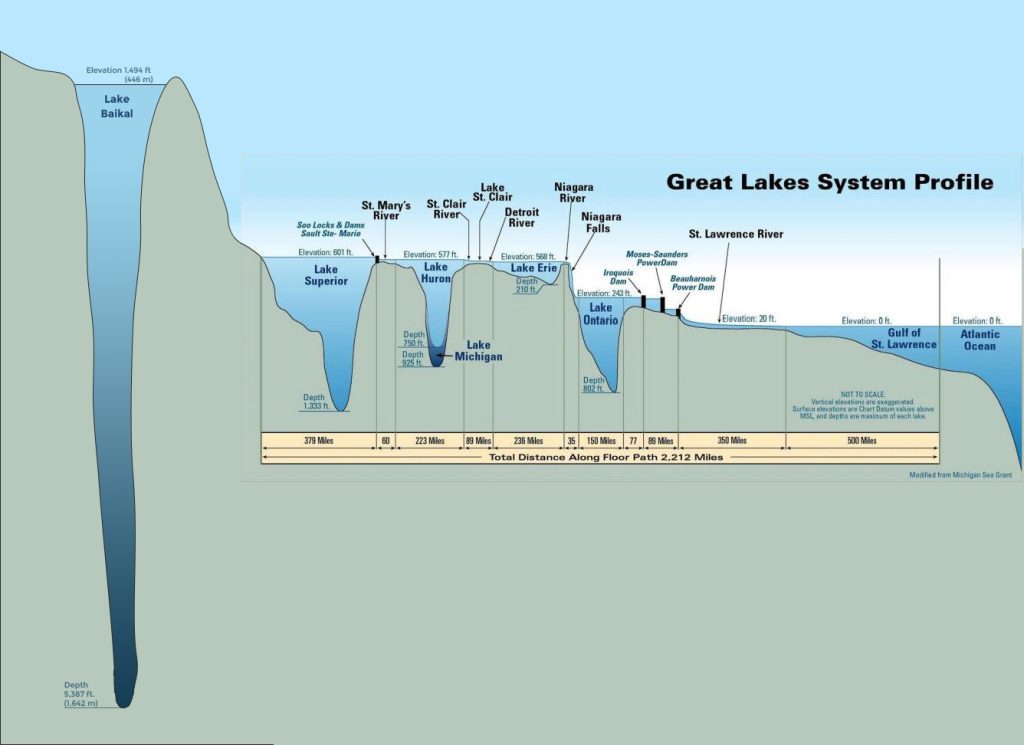

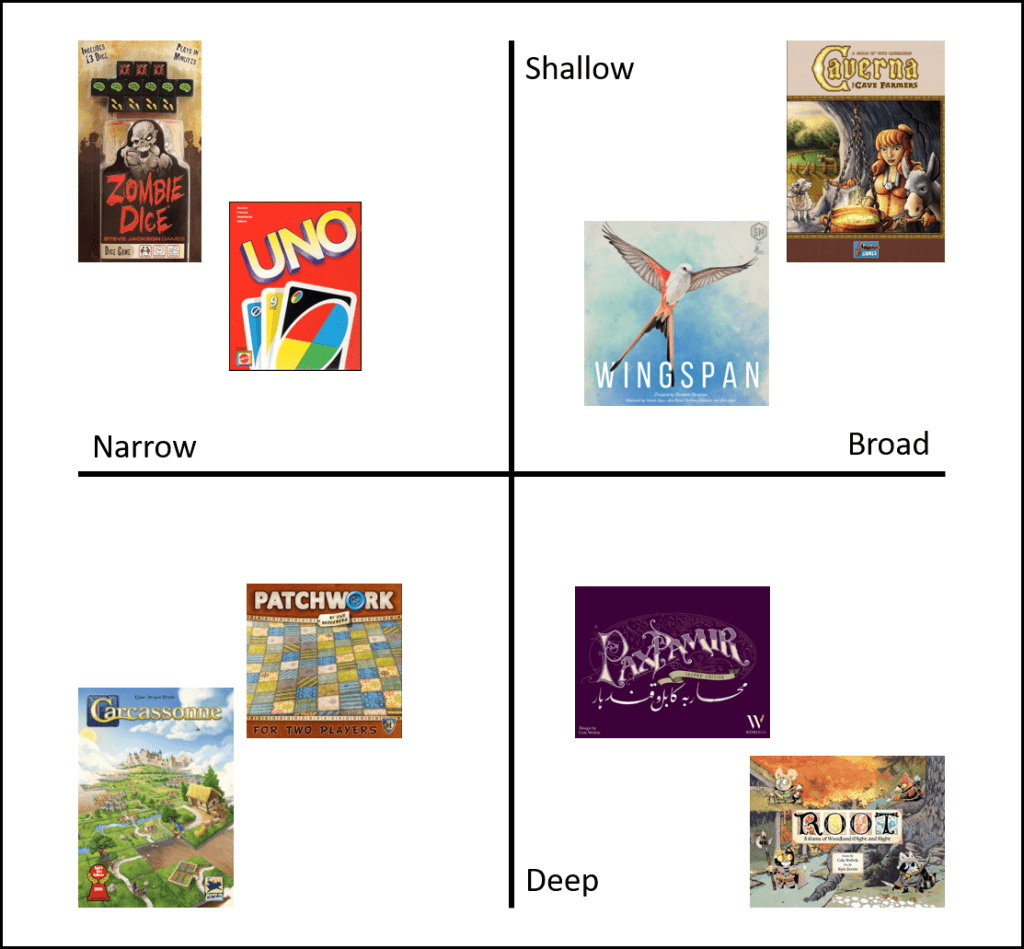

To me, ‘deep’ is a misnomer here. A better term would be ‘broad’. Think of the surface area of a lake stretched out ahead of you. A game like, say, Carcassonne is a narrow little thing that you can paddle across (aka learn the rules to and internalise) in a matter of minutes. A Feast For Odin, however, is like one of the Great Lakes of North America, with the opposite shore so far away that you’ll never make it in a single day.

But depth is hard to parse from a single crossing. It takes repeated trips to even begin to understand how far the waters extend beneath your boat. The breadth of some games belies their actual depth; a broad game could be a Lake Superior with an average depth of 147 metres or it could be shallow old Lake Erie with an average of just 19 metres.

One of my all-time favourite deep games is a strategically rich game from designer Uwe Rosenberg. If you’re thinking that I’m talking about A Feast For Odin, Caverna or perhaps his seminal title Agricola, then you would be absolutely… wrong. The game I’m referring to is Patchwork, and the reason it didn’t cross your mind is the same reason you’re considering closing this window and reading something else right now: easy-to-learn games are rarely labelled “Deep.”

I run into it all the time. The conversation of favourite games comes up, I mention Patchwork, and within minutes someone has said something along the lines of, “Oh, I didn’t care for that one because it was so simple,” or “That’s okay, but it’s really more of a kids game.” Me being the eloquent people-person that I am, I usually suggest that if they find it simple then they’re playing it wrong and that they should try playing it against me to see how rich it really is. Unsurprisingly, that never goes over very well.

Truthfully, though, I can’t blame them. The word that best describes a game like Patchwork is ‘deep’, and it’s been co-opted by games that have 50 times the rules. But Patchwork is a perfect example of a deep game.

At first glance, Patchwork is a simple little game of polyomino placement. It is, however, a uniquely brilliant design from Rosenberg and one whose depths I’m not even sure I’ve fully realized after years of competitive play. I won’t get too obsequious talking about the mechanics of the game, but there’s some amazing stuff there: multiple currencies (time and buttons), variable turn order, and best of all the fact that every piece in the game is laid out in a path at the very beginning.

This may seem like a small detail, but the implications are enormous. By taking away randomness of the draw, the entire timeline of the game, much like another ‘deep’ classic Chess, is spread out before you from the very start, giving you the option to plan and scheme as far ahead as your brain will let you.

Paddling across Patchwork is but the work of a few minutes, which is why it is so easily dismissed alongside broader fare. But that single brief trip barely hints at the richness of strategy that lies beneath. Far from being one of the Great Lakes, the lake profile that Patchwork most resembles is Lake Baikal in Siberia: a deceptively narrow body of water that drops down 1,642 meters, more than four times the depth of Lake Superior (indeed, Lake Baikal holds more water than all the Great Lakes combined, fact fans).

The aforementioned Carcassonne similarly hides a deep well of strategy beneath its unassuming and placid surface (there’s so much going on down there we’ve even written a Carcassonne strategy guide!).

For my money Caverna is an Erie: gloriously broad but fairly shallow. Caverna’s breadth gives the impression of hidden depths that I don’t believe are there. This isn’t a bad thing. Exploring the vast surface waters of Caverna’s gameplay is a central part of the joy of the game, and it’s a great game. You might consider games like Root and Pax Pamir as broad and deep games, whilst games like Zombie Dice and UNO are narrow and shallow.

Treating depth as being synonymous with complexity does no one any favours, not consumers, not critics and certainly not the games themselves.

A Manifesto for a Better Tomorrow

Sometimes I think we as a community fawn over complex game designs because we want a game to feel harder, rather than the act of beating a well-matched opponent to feel harder. We praise the complicated game, celebrating it with the terms heavy and deep. Yet what we mean by these words differs from person to person and both are just used as synonyms for complex.

What’s wrong with complex? It’s defined as consisting of many interconnecting parts or elements. The term complex fits what we’re looking for in a descriptor, prevents harmful ambiguity and avoids meaningless or contextual criteria such as game length or amount of luck.

So here’s our four step manifesto to improve the way we discuss complexity in games:

- Let’s ditch the misleading and harmful weight scale.

- Let’s reserve ‘depth’ for games that hide rich kaleidoscopes of strategy beneath their surface waters, whether those surface waters extend for miles on end or are just the size of a bathtub.

- Let’s use ‘breadth’ to describe those games with lots to explore, regardless of whether the water is a foot deep or bottomless.

- And let’s just call games with lots of rules and rule interactions what they are: complex.

I love& totally agree with your idea but changing the archaic common idea is quite rough

Hi Wern, I’m so glad you like the idea. You’re right though, it feels unlikely at this stage we can change the popular use of the words. But I’ll keep trying! 🙂

Hello. Just read your really good article.

Could you give more examples of deep games? Both from new, underrated classics and modern.

Hi Ryan, thank you, I’m really pleased you liked the article!

I’ve put a list of games below that I believe are deep. It’s obviously very subjective – these are games I’ve played enough to feel like I can sense the depth of them and can remember off the top of my head at this moment!

Terra Mystica (I’ve not played it’s sequels Gaia Project or Age of Innovation but I’d guess they would be too)

Dominion (there’s way more under the hood of this one than people often realise)

Res Arcana

I’ve been on a bit of a Knizia run recently and for me many of his designs are deep games – Tigris & Euphrates (and Yellow & Yangtze/HUANG), Babylonia, Through the Desert, Samurai, even Lost Cities

The two Brass games

Go (many pure abstract games are deep, Go feels like the best example)

Hive

The King Is Dead (second edition)

The Castles of Burgundy

I’m undecided on both Concordia and Great Western Trail, I feel like they might be but I’ve not played them enough yet to know for sure.

Again, it’s a subjective list based on my own experiences. What about you, do you have any examples of games you think are deep?